I have had the privilege of listening to Presidents speak. I have seen famous actors strut their stuff on-stage. I have sat down to chat with war heroes, scientists and seriously wealthy men. However, the most compelling speaker I have ever heard was an unassuming little old British lady named Eve Gordon. During World War II, Eve Gordon was a spy.

Her story was simply mesmerizing. Curiously, I have only found one reference online to her ever having existed. Eve was one of those rare special operators who took her security seriously both during and after the war.

One of the most compelling of her many compelling tales involved her being captured by the Gestapo. Piecing the story together after the fact, it seems she was taken to Amiens Prison in German-occupied France for interrogation and execution. Eve had been working intimately with the resistance forces in the area and could name names. Her handlers knew that she could only hold out for so long. If Eve broke, untold numbers of resistance operatives would die. As a result, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) staged an emergency air raid to either liberate or kill Eve and the rest of her resistance buddies being held at Amiens. They called this mission Operation Jericho.

Eve explained in level tones what the Gestapo did to her. Her interrogation was indeed unimaginably horrible. If you needed any more reasons to despise the Nazis, hearing this grandmotherly figure talk about having her fingers smashed and the skin removed from her back would be adequate to get any normal person energized. While all this was going on, the RAF was making ready.

Operation Jericho orbited around nine twin-engine bombers along with a dozen Typhoon fighters as escorts. The plan was to breach the prison walls in hopes that the shock waves from the 500-pound bombs would spring the interior doors. Heavily-armed resistance teams waited nearby to enter the prison and free the prisoners amidst the chaos. At noon on 18 February 1944, the first wave of bombers came roaring in at treetop level.

The lead aircraft hit the walls with eight 500-pound bombs, each equipped with an 11-second time delay. Given the extreme low altitude, the time-delayed fuses were necessary to prevent shrapnel from the exploding ordnance from damaging the attacking planes. A follow-on flight orbited nearby. If the mission failed and the walls could not be breached, the second group of aircraft had orders to bomb the prison proper and kill everyone inside, friend and foe alike.

It took a couple of runs, but the attack did successfully breach the walls. The second phase of the aerial attack was canceled, and the resistance forces stormed the prison to liberate the captives. 102 of the 832 prisoners perished in the bombing. 74 were wounded, and a further 258 escaped. Counted among the escapees were 79 members of the resistance. Eve Gordon was one of them.

Once she recovered, Eve married an American pilot whom she had repatriated from occupied Norway and then immigrated to America. She spent the rest of her professional career working with hospice programs. The lightning-fast, twin-engine attack planes that had helped spring Eve from the Amiens Prison were de Havilland Mosquitoes.

The Airplane

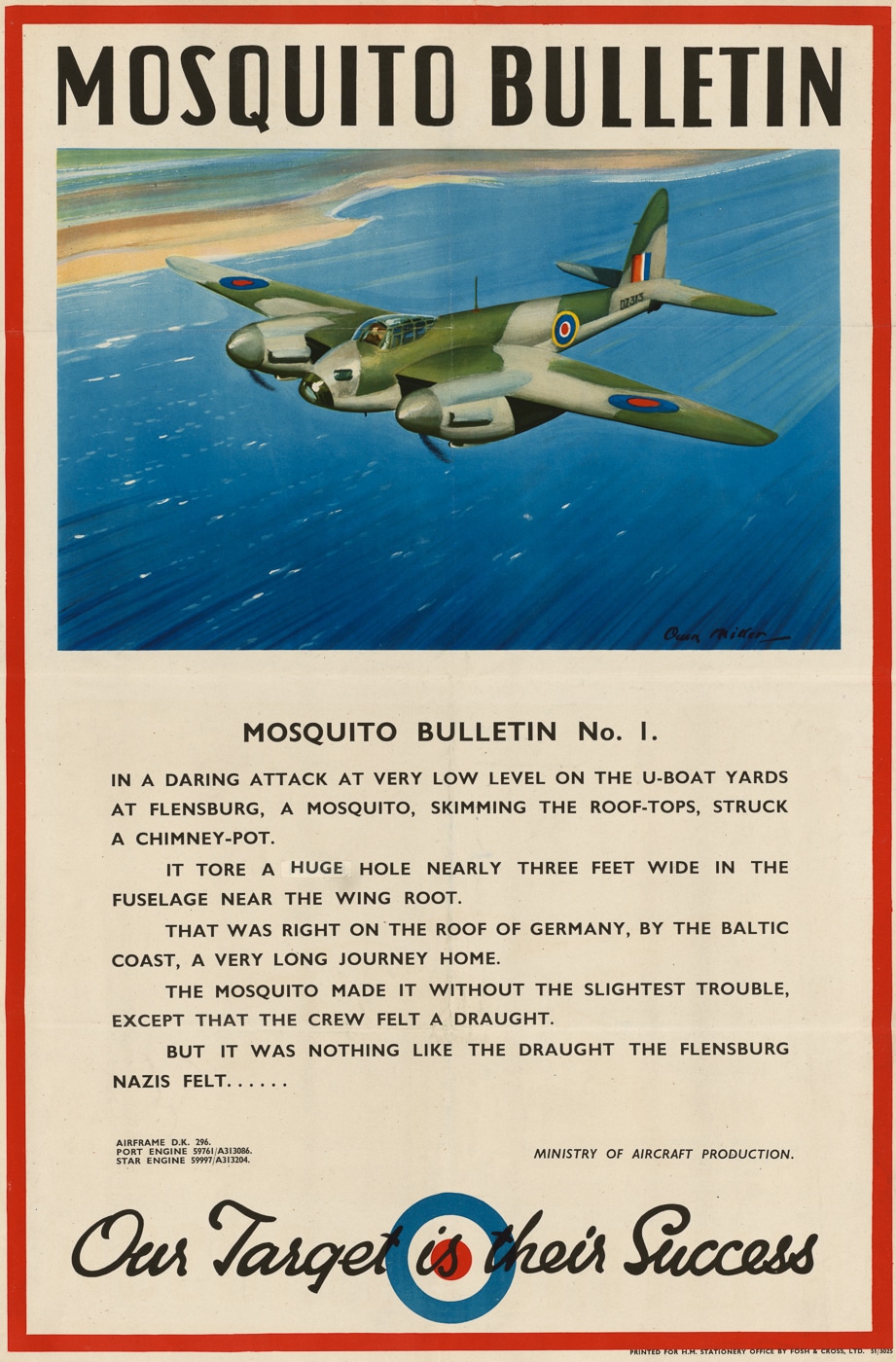

The de Havilland Mosquito was unique in the annals of WWII aviation. Rugged, versatile and unnaturally swift, the Mosquito was actually as fast the single-engine Messerschmitts and Focke Wulfs that they faced in the air over occupied Europe. The reason for the Mosquito’s unnatural speed rested in its unconventional construction. The de Havilland Mosquito was actually made of plywood.

The development path followed by the Mosquito was fascinating. The tender specified an exceptionally fast, twin-engine, lightweight attack aircraft that could be built using a minimum of critical materials like aluminum. Work on the airframe was fairly far along by the summer of 1940. However, the frenetic evacuation from Dunkirk changed absolutely everything. With the German air attack on the British home islands looming large, Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production, directed Air Vice Marshal Freeman to cease work on the zippy bomber in favor of fighter production. Freeman, for his part, ignored the directive. That is the reason that the Mosquito eventually saw combat.

The Mosquito was powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, the same powerplant that drove the Spitfire and the Mustang. With a max takeoff weight of 25,000 pounds and a maximum payload of 4,000 pounds, the Mosquito was a formidable machine. Armament included four 7.7mm Browning machine guns and a further four 20mm Hispano cannons.

In February of 1941, a prototype Mosquito hit 392 miles per hour. This was considerably faster than the Spitfire fighters of the day. Production Mk XVI versions topped out at 415 mph. With a little head start coming across the Channel, German fighters would be unable to climb fast enough to run the Mosquitoes down. This made the Mosquito an exceptionally versatile and survivable platform.

Missions

The Mosquito was indeed produced as a pair of plywood shells fused together along the midline. These shells were built around a balsa core. The airframe was adapted for a wide variety of missions. These included conventional medium bomber, tactical strike, reconnaissance, anti-submarine patrol machine and night fighter. The Mosquito lent itself to conventional daylight level bombing as well as shallow dive attack profiles.

Certain mosquitoes were modified to accept the 4,000-pound Cookie bomb. This piece of ordnance gave the lightweight, fast Mosquito some proper punch. The combination of cannon and rifle-caliber machine guns offered serious firepower when hunting Axis shipping or troop trains. However, where the Mosquito really came into its own was as a recon aircraft.

We take timely, reliable intelligence for granted today. Orbiting platforms combined with ubiquitous drones mean that modern tactical commanders can easily see what’s on the far side of a ridge without putting friendly troops in danger. Back in WWII, however, that was a much harder chore. The answer was fast recon fighters like the American P-38 Lightning and the British Mosquito.

Stripped of armament and equipped with state of the art, high-resolution cameras, these photo-reconnaissance Mosquitoes used their superior speed to get in and get out before enemy aircraft could be scrambled to catch them. In so doing, they provided intelligence that aided tactical commanders in focusing limited resources.

Conclusion

7,781 Mosquitoes were produced during the war. Thirty non-flyable examples remain today. Five airframes are currently airworthy.

Crafted from wood at a time when the state of the art was riveted aluminum, the Mosquito earned its reputation above battlefields all across mainland Europe. The Balsa Bomber was inexpensive to build and played a critical role in freeing the world from tyranny.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here