The USS Lexington (CV-2) served as one of America’s first aircraft carriers, transforming from a battlecruiser design into a symbol of naval aviation power. “Lady Lex” fought valiantly in the Pacific Theater, leaving a legacy that influenced carrier design for generations.

Had history gone a different way, the United States Navy might have operated six battlecruisers. Instead, the first two were converted to aircraft carriers in the 1920s, and the other four were canceled entirely. It wouldn’t be hyperbole to suggest that those two vessels helped ensure America’s victory in the Second World War.

Wrong Course

A great irony is that the Lexington-class battlecruisers were also developed in response to the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Kongō-class battlecruiser, the first of which was actually built in the UK.

At the time, the vessels were seen to feature an effective mix of speed, armor and firepower.

However, naval historians now acknowledge that the concept had significant flaws notably that battlecruisers offered little savings in construction costs, yet were far more vulnerable than true battleships. As the large capital battle wagons became faster and armor protection was further improved, the battlecruiser concept became largely obsolete. In that regard, the United States Navy likely dodged a bullet. The two ships converted to aircraft carriers, USS Lexington (CV-2) and USS Saratoga (CV-3), proved invaluable when they were literally needed most.

The Washington Treaty

Following the First World War, attempts were made to prevent another conflict and the naval arms races of the early 20th century, notably the one between the UK and Germany. The Five-Power Treaty, also known as the Washington Naval Treaty, was negotiated at the Washington Naval Conference in late 1921 and early 1922. The British Empire, the United States, France, Italy, and Japan were its signatories.

It limited the construction of battleships, battlecruisers, and aircraft carriers. Not surprisingly, the various signatories sought to exploit loopholes, some of which were closed with the follow-up London Naval Treaty.

The United States canceled the battlecruiser program, with the first two warships converted to aircraft carriers during construction. Washington also used a loophole that allowed the 43,500-ton warships to be converted into carriers, each with a capacity of 33,000 tons. Yet, because they were already under construction, their respective displacement was increased to 36,000 tons, even as the treaty limited such vessels to 25,000 tons. The U.S. took advantage of a clause that specified the added weight would not be included if it was for providing protection from air and submarine attacks. The result was quite capable warships.

For several years, CV-2 and CV-3 were the largest aircraft carriers in the world, outfitted with flight decks that were 901 feet long and 100 feet wide. Moreover, the ships were equipped with lowerable crash barriers, a simple yet still significant innovation that enabled the carriers to quadruple the landing rates of aircraft.

Each carrier operated with 86 aircraft, whereas the Royal Navy’s converted HMS Courageous operated with only half the number of warplanes.

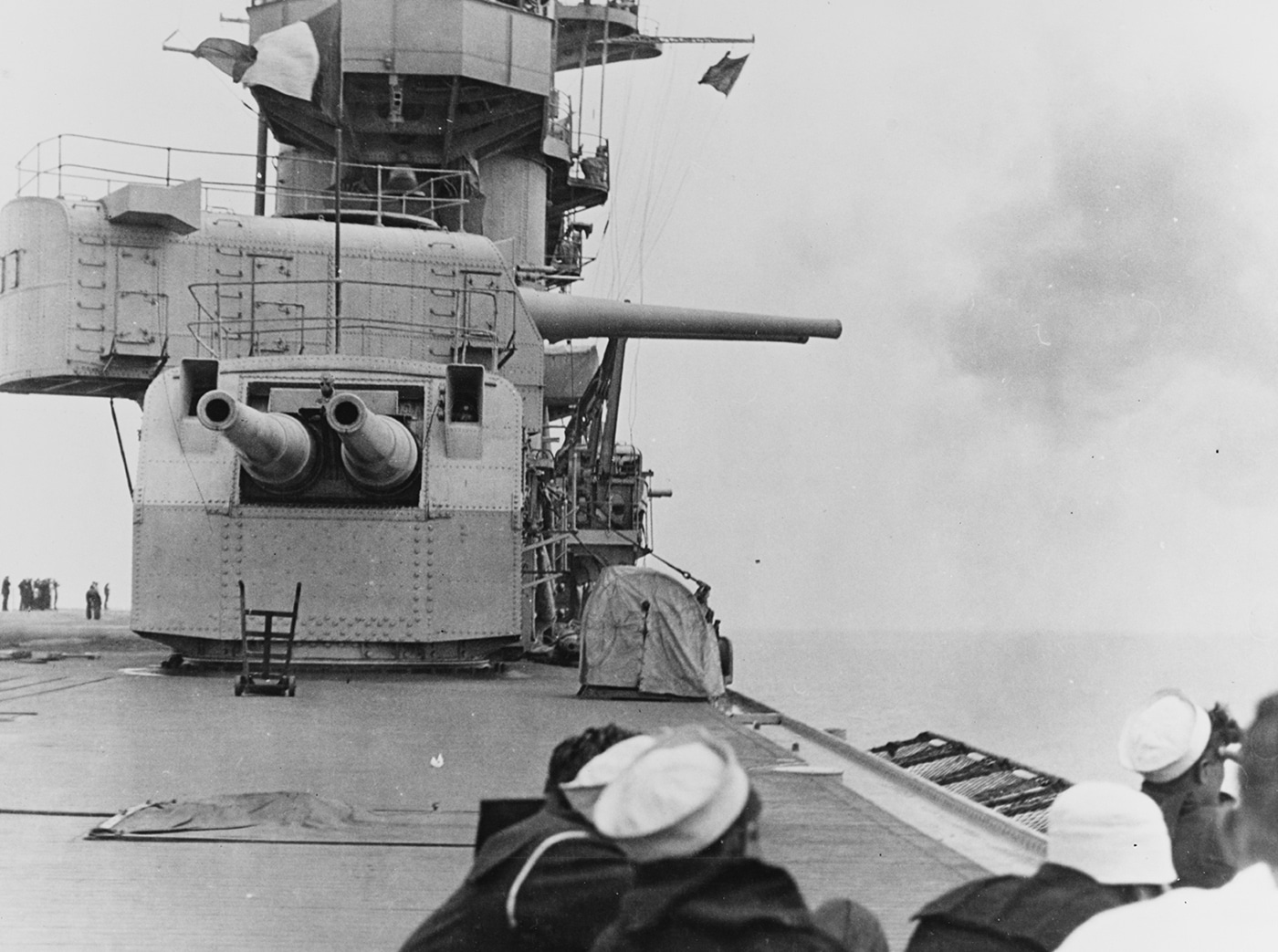

Yet, as naval aviation was still in infancy, there were still those who believed aircraft alone were not enough, and the Lexington-class were armed with eight 8-inch guns and a dozen 5-inch anti-aircraft guns. When the carriers were commissioned in late 1927, they were still considered “experimental,” but it was an experiment that proved to be highly successful.

Readying for War

During the 1930s, USS Lexington and USS Saratoga were employed mainly to develop and refine carrier tactics via a series of naval exercises. During the training drills, each aircraft carrier launched simulated “surprise attacks” on Pearl Harbor and even on the West Coast of the United States. The first mock attack was carried out in February 1932 as part of Grand Joint Exercise No. 4, and again during the Fleet Problem XIX drills in March 1938.

Such exercises should have been a portent of the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, yet any concerns were downplayed. Many naval officials of the era still put their faith in battleships, not aviation. Ironically, USS Lexington and the U.S. Navy’s other carriers were among the targets that IJN hoped to sink in its raid on Pearl Harbor, but by chance, none were at port on that fateful Sunday morning.

As the Japanese carried out the sneak attack, USS Lexington was part of Task Force 12, under the command of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, having departed Pearl Harbor two days earlier. Joined by three heavy cruisers and five destroyers, the carrier was transporting Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 213 with 18 Vought SB2U Vindicator carrier-based dive bombers to Midway.

Rear Admiral John H. Newton, commander of the carrier task force, received word of the attack on Pearl Harbor and was ordered to rendezvous with Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey and search together for the Japanese fleet. Some historians have suggested that the aircraft’s search mission would have been better carried out from Midway, but instead, USS Lexington began the search. With more than eight decades of hindsight, it is easy to see that this could have ended in disaster for the United States Navy, as the carrier could have been lost in such a battle with the IJN.

After the attack, CV-2 returned to Pearl Harbor, staying just two days before heading back to sea, where she was ordered to part in the soon-to-be-aborted attempt to relieve Wake Island. Again, that decision was likely for the best.

In early 1942, Task Force 11 was spotted by Japanese submarines near the Johnston Atoll, but depth charges launched by the carrier’s Douglas TBD Devastators allowed the flotilla to avoid another disaster. There were reports that at least one Japanese submarine had taken damage.

CV-2 and Lt. O’Hare’s MoH Flight

Beginning on January 11, 1942, USS Lexington patrolled the Oahu-Johnston-Palmyra triangle, monitoring for Japanese activity. Just over a month later, as the flagship for Vice Admiral Brown, CV-2 departed to raid Rabaul in eastern New Britain, Papua New Guinea, which had fallen to the Japanese.

Its capture had caused great concern in Australia, as there were fears its harbor could serve as a marshalling and supply center for the IJN’s carriers and other warships. It also meant that the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, New Hebrides, and New Caledonia were within striking distance of Japanese forces.

Brown called for USS Lexington to move to within 125 miles of Rabaul in the nighttime hours, and then at 0400 hours (4 am) on February 21, launch aircraft to strike the Japanese. It didn’t go as planned. On the morning of the 20th, 350 miles east of Rabaul, CV-2’s radar picked up incoming Japanese aircraft, and the American carrier came under attack with two waves of nine aircraft each.

The air wing of USS Lexington responded, shooting down most of the attackers. Although the raid on Rabaul was canceled, in total, 18 Japanese aircraft were destroyed, with the loss of two planes and one pilot from the U.S. carrier.

It was during that action that Lt. Edward “Butch” O’Hare, flying a Grumman F4F Wildcat, became the first U.S. Navy “ace” of the Second World War. O’Hare was one of just two fighters available when the second wave attacked. He was credited with engaging nine Japanese bombers that approached the carrier, and he single-handedly shot down five Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers, one of which attempted to crash on CV-2’s flight deck.

For his actions, O’Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor.

However, O’Hare didn’t survive the war; he was killed in action in late November 1943 during the Battle of Tarawa. The United States Navy named DD-889, a Gearing-class destroyer, in his honor, while Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport is also named for him. A Grumman F4F-3, similar to the one he flew during the Medal of Honor action, is now on display in the airport’s Terminal 2.

Battle of Coral Sea

On May 6, 1942, the Philippines fell to the Japanese forces. It was a significant setback for the Allied forces in the Pacific, paving the way for the IJN to move southward virtually unmolested. Two days before the final U.S. and Filipino forces surrendered in the Philippines, the first naval engagement in which carriers fought one another had begun, and the first without the warships seeing or firing each other directly.

The Battle of the Coral Sea has been described as a battle of errors, with both sides making costly mistakes. It was also the first time that the Japanese advance in the Pacific was checked.

The U.S. Navy had an advantage as it had learned of Japanese movements through signals intelligence and dispatched two carrier task forces, along with a joint Australian-American cruiser force, to oppose the offensive. USS Lexington and USS Yorktown (CV-5) arrived and began to search for the enemy.

On May 7, 1942, seaplanes spotted an enemy task force, and CV-2’s air group was launched, followed shortly after by aircraft from CV-5. In total, 92 planes flew to the coordinates provided by the search aircraft. They found nothing but stormy weather.

Then Lt. Commander Weldon L. Hamilton, flying a Dauntless dive bomber from CV-2, spotted an IJN task force consisting of four heavy cruisers, one destroyer, and most notably the light carrier Shōhō. Hamilton alerted the air group, which shortly after began its attack. Shōhō became the first Japanese carrier to be sunk by aircraft from a U.S. Navy carrier.

It prompted the now infamous radio message from Lt. Commander Robert Ellington Dixon of, “Scratch one flattop!”

The warship went down quickly with 631 men on board, while only 132 of her crew were rescued. Shōhō was just the first, but not the last, carrier to be lost in the engagement.

As the first significant battle between carrier planes, both sides learned valuable lessons, notably the performance of each other’s aircraft. Japanese aviators found that the American warbirds were tough and rugged, which added to the challenge of shooting them down. Even the Devastators, which should have been replaced by more capable aircraft, served with distinction. Of the 92 aircraft launched, all but three returned from the initial sortie.

The next morning, the U.S. sought to find and attack the fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. In the late morning, a Devastator attack was carried out on the Shokaku, inflicting heavy damage, forcing the IJN carrier to withdraw.

However, the returning U.S. aircraft found that both USS Lexington and USS Yorktown had come under attack. At 1120 hours on May 8, two Type 91 torpedoes had struck CV-2. It was followed by multiple aerial bombs that crippled the American flattop. A 1,000-pounder even destroyed the cabin of Admiral Aubrey Fitch, who had taken command of the Task Group 17.5 from Brown.

Fortunately, the Japanese fleet was in no shape to press on. With the loss of its light carrier, along with a destroyer and several minesweepers, plus the damage to Shokaku, the IJN was forced to head for home. It seemed like an American victory.

That changed as the day continued.

CV-2’s crew spent much of the day fighting the fires that had broken out, but by the late afternoon, it became apparent that the carrier couldn’t be saved. The fires were uncontrollable, and an internal explosion knocked out the ship’s engine room ventilators. There were very real concerns that the heat would detonate the ordnance on the hangar deck and storage areas. The decision was made to abandon ship, with the flag transferred to the New Orleans-class cruiser USS Minneapolis (CL-36).

Admiral Fitch told Captain Frederick C. Sherman, commanding officer of USS Lexington, “Ted, let’s get the men off.”

More than 300 sailors descended from lifelines into the warm waters of the Coral Sea. Fitch and Sherman were the last to leave the doomed carrier. Although 216 had been killed in the attacks, every living soul on board, including the captain’s dog, was subsequently rescued by that evening.

Surprisingly, despite the pounding she had taken, USS Lexington wouldn’t sink — a lasting testament to her design and construction. Flames continued to shoot hundreds of feet in the air.

Finally, at 1915 hours, the Porter-class destroyer USS Phelps (DD-360) fired five torpedoes into CV-2 to ensure the carrier wouldn’t be captured by the IJN. USS Lexington became the first United States Navy aircraft carrier lost in the conflict, although the USS Langley (CV-1), which had been a collier converted to a carrier and then to a seaplane tender, had been scuttled two months earlier.

On June 24, 1942, USS Lexington was officially struck from the Naval Register.

Legacy of USS Lexington

The loss of USS Lexington was a heavy blow for the U.S. Navy, but it was part of the price paid to halt the Japanese expansion. Although her service in the Second World War was just over five months, she was awarded two battle stars, along with the American Defense Service Medal with “Fleet” clasp, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

On March 4, 2018, an expedition to the Coral Sea led by Microsoft founder and philanthropist Paul Allen from the research vessel RV Petrel discovered the remains of CV-2. USS Lexington remains at a depth of approximately 9,800 feet (3,000 meters) at a distance of more than 500 miles (800 kilometers) from Queensland, Australia.

The name USS Lexington also lived on with the Essex-class carrier, CV-16, which was commissioned in February 1943. She went on to see extensive service in the Pacific War and remained in service until 1991. She is now preserved as a museum ship at Corpus Christi, Texas. Although her surviving sister ships — including the USS Yorktown (CV-10), USS Intrepid (CV-11), and USS Hornet (CV-12) — have lower hull numbers, CV-16 was laid down and commissioned earlier, with USS Lexington now remaining the oldest remaining fleet carrier in the world.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here