There’s nothing wrong with hunting with an old, classic rifle. Here, we take a closer look at the pre-war Model 70 Winchester.

Sometimes you get lucky. And sometimes not.

Back in the early 1990s, the boss took in a Winchester Model 70 chambered in .30-06, a thoroughly plain and ordinary rifle. Too bad the stock was too long, and it kicked him hard. So, he sold it to me for what he paid: $200. Even in 1992, that was a steal, but hey, that’s what he paid, so not a big deal, right?

The stock fit me, and besides, I had an M70 stock with a rubber recoil pad on it in the shelves, someplace, if I needed to change from the steel buttplate. (I did have it, and I did.)

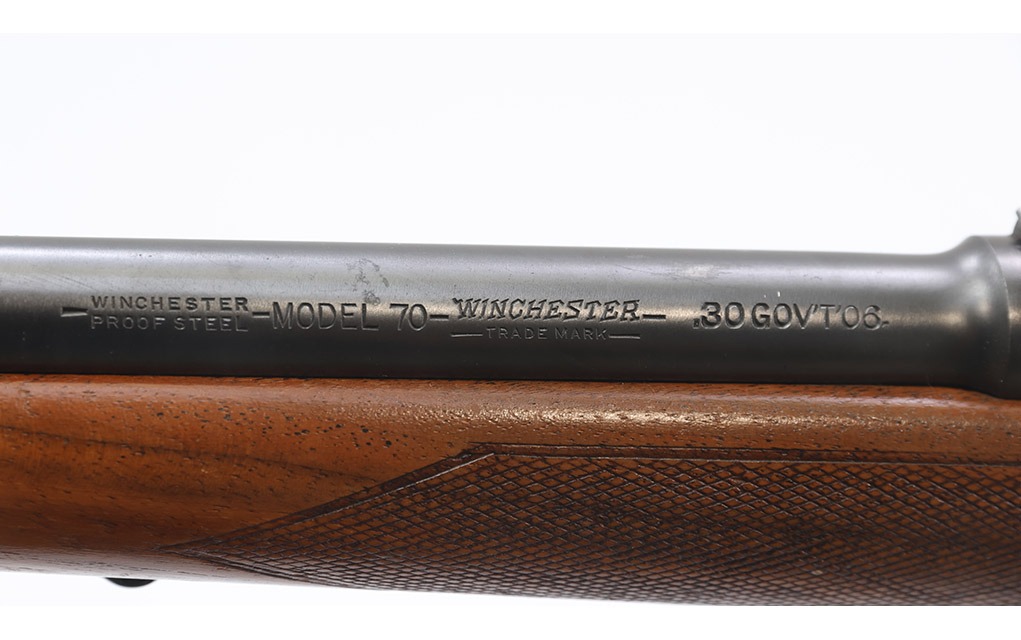

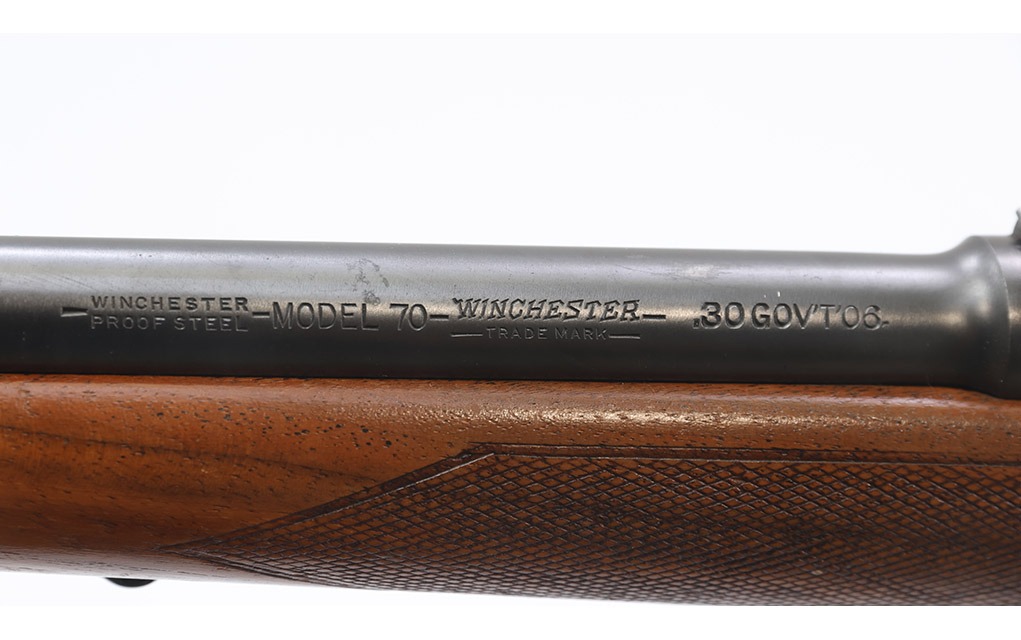

I looked at the serial number and thought, Hmm, that’s an early one. Yes, it is. In fact, it was made in 1941. It’s in the group known as the “Type I-2,” and it has the stripper clip slot in the receiver bridge, the flag-shaped safety lever that works the wrong way, and the bolt handle has a different contour and angle compared to the postwar rifles.

After doing some research, I found that the hallowed “date stamp” on the underside of barrels was only the date the barrel itself was made. It apparently wasn’t uncommon for a batch of barrels to be made one year and then installed in receivers in subsequent years as that caliber was ordered. But I guess by 1941 they had used up the older barrels, and the barrel-making line was just keeping up with the receiver making line because mine is dated 1941. In fact, it is dated “41” and “1906” because that’s how they denoted date and caliber.

By 1941, Winchester was busy making M1 Garands, having started deliveries in December of 1940. Little did they know what “full production rate” was soon going to entail.

So, mine was assembled halfway through the year of 1941, and it might well have taken some time to get from the Winchester assembly area to shipping, to a distributor and then to a gun shop someplace. It’s entirely possible that it was resting in a rack in a gun store or hardware store on December 7, 1941. Who knows.

Details of a Classic

The Model 70 was the evolution of the Model 54, which was itself essentially an American-made Mauser 98. It did change some things from the Mauser—some good and some kinda meh. One change was the trigger. The Mauser trigger, though a marvel of durability and simplicity, depends on a spring-loaded leverage design to release the sear. While it’s practically indestructible and end-user fool-proof, it’s not easy to adjust. Well, you can’t adjust it, short of doing polishing, cutting, carving … all things off of the DIY list for firearms.

The Model 70 trigger has small nuts on threaded shafts, with lock nuts as matching sets, and you can adjust it to be pretty darned good. Oh, you can over-adjust it, but hey, everything with adjustments can be over-adjusted. Since it was set from the factory to be really nice, most never got adjusted. The few I had to work on as a gunsmith had been over-adjusted by their owners, and all I did to fix the problem was to set them back to factory standard, and life was good again.

The barreled action rides in a one-piece walnut stock with cut checkering, and the bottom metal is held in place by three screws. The magazine plate is hinged and held shut with a spring-loaded button at the rear, so to unload you just press the button, swing the bottom plate down to dump the rounds out of the magazine, and then open the bolt to extract the last round.

Another good thing was the front action screw. It went up through the bottom metal and stock to enter a threaded hole in the center of the generously sized bottom of the action. So when you torque the action screw, there’s a good surface area for the screw to pull the action down onto the stock. This is unlike the Mauser with the front action screw in the front recoil lug. The unfortunate result of that is the tightening of the action screw essentially makes the stock lug a fulcrum, and it needs more fussing in bedding the action.

Also, the Mauser comes with less area for the pulled-down action to rest on in the stock. In the days (decades really) before glass-bedding, this mattered. And when glass-bedding did get invented, the Model 70 had much less need of glass-bedding to keep it from getting twitchy as far as bedding was concerned.

One aspect of bedding that is a real head-scratcher these days is the barrel screw. The what? Yep, it was felt back then that, in order to control barrel movement, it was a good thing to tighten a screw into the barrel, out on the forearm, and keep it from flopping around. This also happened to be, on the 70, the boss where the rear sight was located.

Free-floating barrels? In the era of wood stocks, that wasn’t a thing. Oh, and the front sight? Nothing so déclassé as a ramp bolted on with screws. The front sight ramp is an integral part of the barrel, with a dovetail for a front blade and a front blade hood to protect it.

If you wanted other sighting systems back then, Winchester had you covered. Ever wonder where the mounting of scopes on top of the receiver with four screw holes top dead center came from? Well, if it wasn’t Winchester who invented it, the adoption of that for the classiest American rifle sealed the deal. Right from the beginning, Model 70s were set up for scopes.

She Ain’t Perfect

There was an oddity, and that “meh” I mentioned.

The oddity is the safety. The prewar safety is one I call the “wrong way” safety. The 70 safety is a three-position design. All the way on, it won’t fire, and you can’t work the bolt. In the middle, you still can’t fire, but you can work the bolt, and Fire is, well … Fire.

When it’s on Safe, it’s crossway over the cocking piece, and it blocks your view of the sights. But, to swing it to Fire, you have to reach up with your thumb (right-handed shooters, I have no idea how you southpaws would manage this) and pull the safety lever back toward you and rotate it fully to the right side. With iron sights, it isn’t too fussy … but with a scope on top, it can be a real problem. Fat thumbs, gloves and cold weather—all can conspire to make it a real hassle.

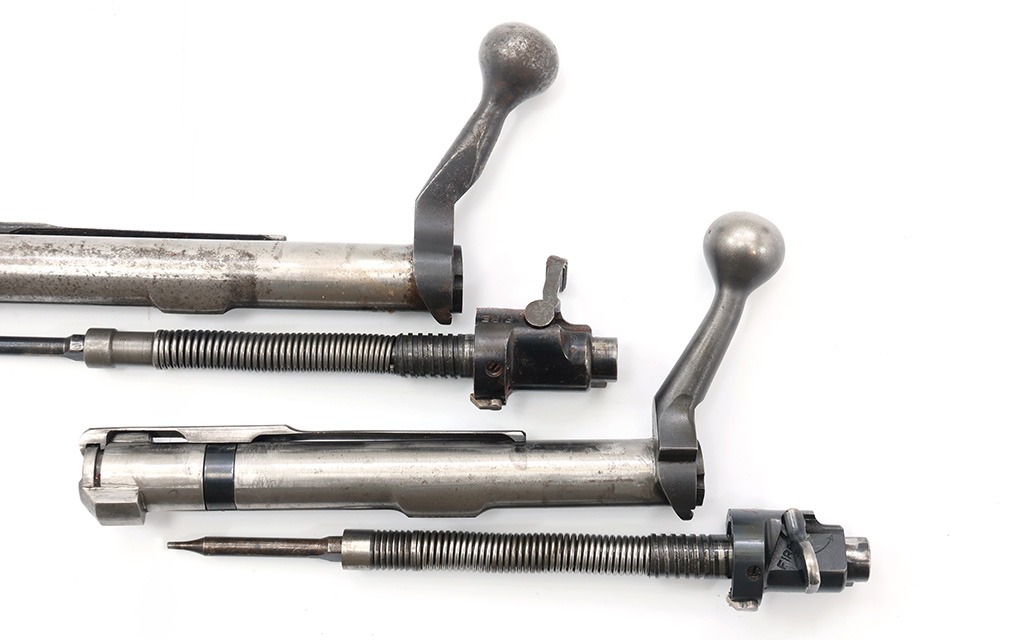

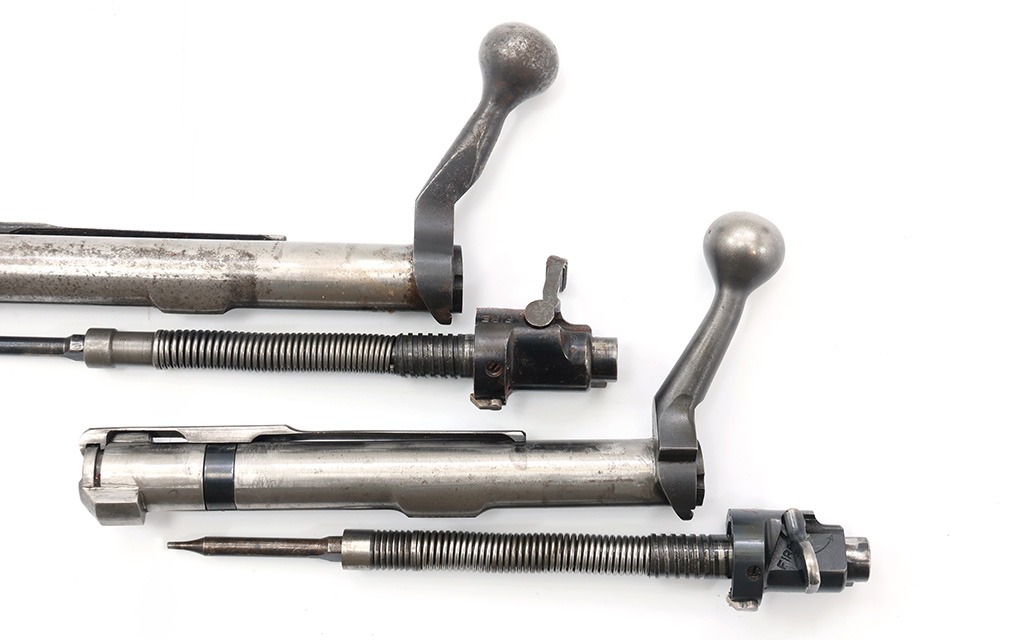

The 70 has a controlled-feed extractor, just like the Mauser, which was the standard of the day. It’s a big, stout, spring steel extractor, and it can readily be removed in stripping the 70. In fact, you can remove the bolt and disassemble it with your bare hands, no tools needed, like the Mauser. And that I liked, because I would see rifles in the gun shop every year where the petrified-oil-bound or dust-and-lint-caked striker spring couldn’t muster enough oomph to set off primers. Once I looked, I could promise next-day or even while-you-wait correction to my hunting customers.

And the meh? Then, there was the famed “coned breech.” This was adopted because (I guess) it was a feature on the ’03 Springfield, and as a result, the best rifles had to have it.

OK, muster up the 3D modeling software in your head, and imagine the back end of the barrel. On a Mauser, that back end is square to the bore. The extractor has room to work because that gap exists all the way around the barrel. OK, now, on the 70 (and the Springfield) grow that back end of the barrel, like a funnel, except where the extractor has to reach to the chamber. That’s the coned breech. The supposed advantage was that it provided better guidance to the cartridge tip and prevented jams. (All those who have had such a jam with a Mauser, please raise your hand … I thought so.)

While it didn’t increase reliability, it did create a headache for gunsmiths. Fitting a new barrel to a Mauser is simple, if exacting. But once you’ve fit and headspaced a Model 70, you then have to carefully mark the barrel, remove it from the action, mill the extractor clearance slot through the edge of the coned breech and reinstall it.

Lady in Waiting

My intention with this rifle was to get it set up for hunting … and then hunt. Well, in the 30-plus years since I acquired it, I have done that exactly not once. It has had two or three different scope bases and rings on it and a half-dozen scopes, all pulled off for some other project. It once again has the scope and rings on it that it was wearing when it first arrived here. I’ve used it in articles, and chrono’d ammunition in it, but I’ve never had the chance to hunt with it.

And as time goes by, it’s in very nice shape; it might get to be too much of a collectible to hunt with. (Yes, I have the original stock around here … someplace.)

And then, just in time for this article, I scored another Model 70 at a really good price. It needs some scrubbing, and it’s a better candidate as a hunting rifle. It’s a postwar rifle, made in 1952, with a “52” barrel date on it … which I find mildly amusing. Both of my Winchester Model 70s were made at a time when Winchester was distracted by making Garands. The first one for World War II, the second for Korea.

The postwar safety works as we expect, being fully on the right side, and working just fine underneath a scope. The barrel marking is also different. Pre-war, they marked barrels in .30-06 as “30GOVT06”. Postwar Winchester went to “30-06-SPRG.” They also did away with the stripper clip slot, postwar.

We will not speak of the changes made for the post-64 rifles, which is a painful subject to be discussed later. And, that’s assuming I can bring myself to acquire one of those [shudder].

You may be thinking, Well, old rifles may be nice, but so what? They knew how to make rifles back then. In fact, the Model 70 was pretty much a hand-built rifle, which wasn’t unusual in the days (decades, again, really) before CAD-CAM and CNC machining. The bolt is so slick that people who handle a pre-’64 70 think that it has been hand-lapped or something. Nope, just really slick.

And, they’re plenty accurate enough. No, you are not going to post a competitive score in a PRS match with one, since it won’t shoot sub-half-MOA ever, let alone all the time. But can you? And will the deer or elk care that you are using a “merely” MOA rifle?

My pre-war Model 70 is a walnut and steel rifle, from a time when hunting was hunting—not sniping—and the latest thing in synthetic materials were nylon stockings. I’ll admit that at 8 pounds bare, and over 9 pounds once there’s a scope, sling and ammunition onboard, it isn’t a mountain rifle. But that weight comes in handy when you touch off a .30-06.

Put a muzzle brake on it, you say?

Heresy!

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the September 2024 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Hunting Rifles:

Read the full article here