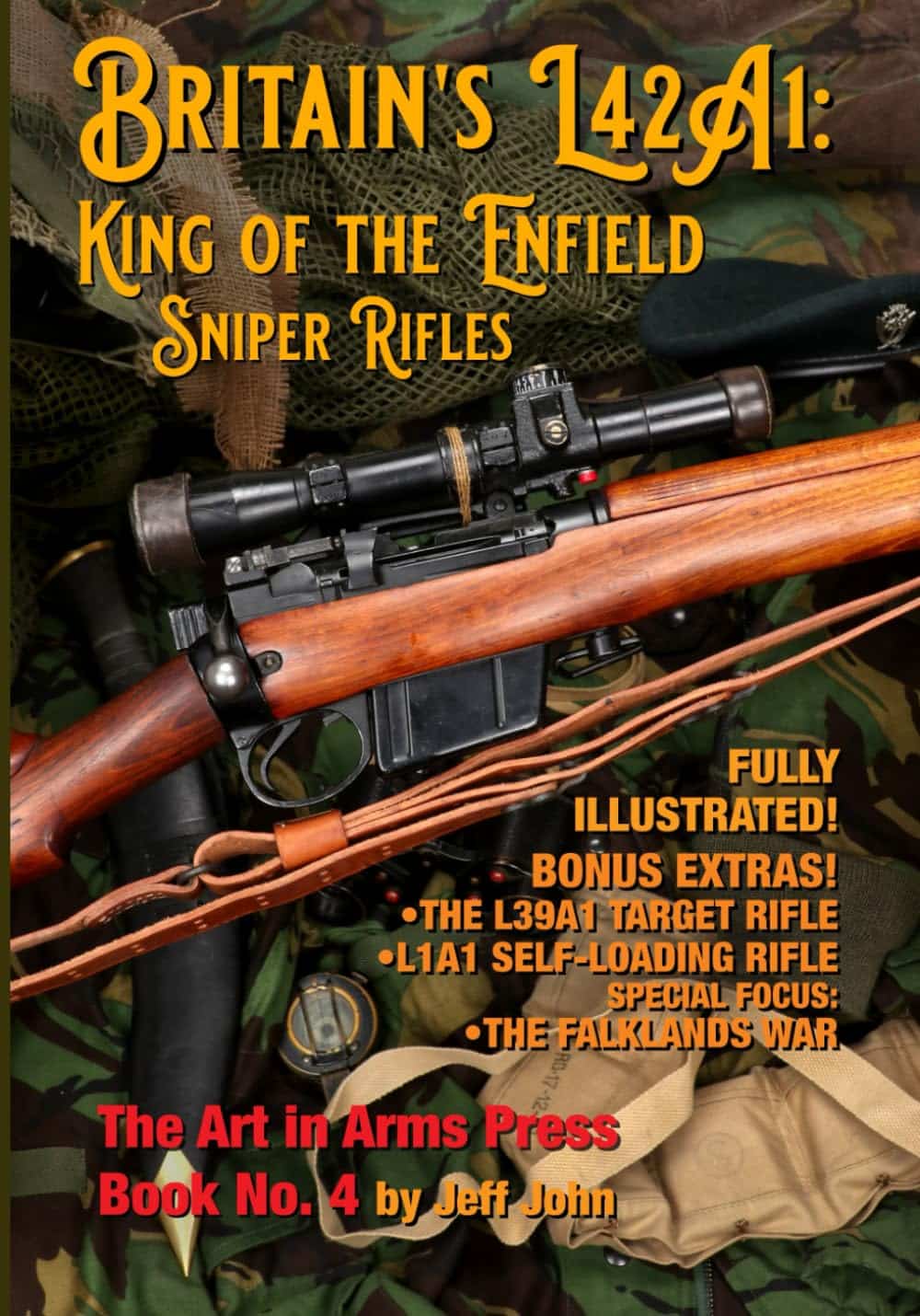

Editor’s Note: For more about the fascinating history of the L42A1, read Jeff John’s new book Britain’s L42A1: King of the Enfield Sniper Rifles available at Amazon.com.

Nothing better than being good and lucky. The L42A1 sniper rifle is a case in point. The atomic era began in 1945 with propellor aircraft and bolt-action rifles woefully obsolete overnight and all nations faced with rearming from the top down with atomic missiles, jet aircraft and replacing those antique bolt rifles with full-auto machine rifles. The Soviet Union was racing to do so, was right at free Europe’s door after enslaving Eastern Europe, and hungrily anticipating the rest. Only the United States stood guard until Europe recovered.

In the face of all this, Britain disbanded their Scout/Snipers so valuable during WWII and Korea. Only the Royal Marines kept the concepts and talents alive while still fielding arguably WWII’s best sniper rifle in the Enfield No. 4 Mk I (T) .303 alongside their new 7.62×51 L1A1 Self Loading Rifle. The uneasy peace of the Cold War didn’t mean the rest of the world wasn’t smoldering. Troubles began in Ireland in the late 1960s, and an insurgency in Oman became a serious threat.

All of a sudden having a capable man able to deliver a single precise shot instead of a fusillade once again proved a necessity. It takes time to develop a weapon from scratch, time Britain didn’t have. The Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield provided a simple, elegant solution.

Fertile Grounds

Target shooters had plowed the way. Military rifle competition shooting was very popular in England, with most competitors happily shooting Enfield No. 4 rifles in .303. As stocks of surplus ammo began running out in the early 1960s, many — especially the Army teams — wanted to compete with the new 7.62×51 NATO service round, preferably in a bolt action.

Easy peasy! In the early 1960s, Enfield had developed a 7.62 conversion package for the No. 4 rifle so Commonwealth countries could easily convert No. 4 rifles in case Britain needed rifles quickly while transitioning to the L1A1 SLR. But those converted rifles didn’t shoot well. Maddeningly, they — as a rule — shot better than the .303 out to 200 yards, couldn’t compete from there to 600, and excelled at the longer ranges. There was no easy fix.

After much experimentation, Enfield’s ingenious solution was to free-float a 27.5-inch long, heavy, hammer-forged 7.62×51 barrel onto the No. 4 with a fore-end shortened to the front swivel. Bingo! These very accurate L39A1 target rifles were made available to the Army teams and the public in the late 1960s — just as the Army higher-ups realized the need for a sniper rifle, with no time to design one from scratch and the obsolete .303 a poor option.

Onward and Upward

This was how Britain backed into a best-of-class sniper rifle — again. The 7.62 L39A1 front end was mated to select No. 4 Mk I (T) rifles still in stores. Some rifles were numbered in the same series as the L39A1, and this is one of those. Oddly, there doesn’t seem to be a pattern to which ones had the old numbers removed, and ones having their original serial numbers retained since they appear with similar dates.

Unlike the exemplary craftsmanship used in scrubbing off the original markings of the L39s, L42s like this one had the original serial numbers crudely ground off, then new ones added. However numbered, all share a new “L42A1” model number on the left side of the receiver, the stylized “ED” for Enfield, and the year the conversion was completed. Receivers were modified underneath for the 7.62 magazine, but little else had to be done.

The barrel got a sturdy military-style front sight protected by twin wings. The rear sight was left alone. When the range was read in meters instead of yards, it was deemed close enough to the 7.62’s trajectory to require no modification except one. As originally designed, the rear sight had to be raised to remove the bolt for cleaning. WWII snipers were loath to do so even though the scope would return to zero within 1 MOA or less. Good, but not good enough. Armourers in the field relieved the underneath of the sight so the bolt could be removed without first removing the scope. The L42 rear sights were given this sensible modification.

An Eye for Precision?

Optics were a problem. Few scopes in the 1960s were as reliable or as sturdy as the WWII No. 32 aboard the No. 4 (T), but the early scopes were difficult to zero, so only the perfected late war No. 32 Mk III 3X scopes were installed. Those scopes were gone through, had new elevation turrets installed for the 7.62’s trajectory and waterproofed.

Their WWII stock number was lined out and a new NATO Stock Number added. The scope’s serial number was stamped on the top of the stock’s wrist. If the original stock was retained, the WW II Mk I or Mk II scope number was X’d, lined through or filed off. The scope mount was numbered to the rifle.

Hands-On

These rifles were legendary for accuracy and reliability. This one in my collection shoots remarkably well. My best five-shot group was ⅝ of an inch at 100 yards with Black Hills ammo topped with 168-gr. Sierra Tipped MatchKing bullets. Anytime match ammo was fired, there would be three or four shots hovering around a ½ inch. Standard ball shoots well, with five shots of surplus Winchester-made Lake City ball ammo giving a 1⅜-inch group and surplus Swiss Saltec a 1½-inch one.

To shoot this well requires some technique. One detraction of these Enfields is their slippery brass buttplate. To shoot the rifle well, it is important to physically place the butt back into your shoulder pocket after cycling a round. The length-of-pull is a short 13 inches, and it is also important to pull the rifle in tightly to consistently to shoot it well.

These rifles were set up to be shot prone, and the scope is far enough forward to do so. The comb riser is sufficient to give a good cheekweld. The scope is a little too far forward to use from the bench without crawling up on it, but it isn’t too hard.

Conclusion

Only about 1,200 L42A1 rifles were made, but the records are sketchy. The L42 was replaced in mid-1980s by the Accuracy International L96, and it was retired after the first Gulf War. About 640 rifles were imported by Navy Arms in the early 1990s. They were mixed with L39A1s, so the quantities of each are unknown. Many were destroyed, but somebody got the bright idea that some should be preserved as a baseline for accuracy and reliability. Some of those served in Iraq and Afghanistan as late as 2005. Not a bad legacy for a rifle first adopted in 1888!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here