We dive into the history and ballistics of the .280 Remington cartridge and try to figure out if the cartridge remains relevant today.

The .280 Remington is limping along to extinction, which is both understandable (for reasons we’ll get into) and also quite a shame.

It came along too early or too late depending on one’s view, got sandbagged by poor marketing and, in general, never caught on enough to enshrine itself as one of the All-Time Greats.

As a result, in my opinion, .280 Remington is asymptotically winding down to oblivion. The dying cartridge has positives, but there’s nothing it does so well that you can’t find equal performance in what are more popular and in many cases more desirable cartridges.

Where Did .280 Remington Come From?

As the Remington cartridge division has been apt to do throughout its history, it devised the .280 by adopting a 7mm-06 wildcat that many basement ballisticians were mucking around with. First commercially released in 1957, Remington declined to offer the cartridge in the 720 series initially, instead opting to only (at first) chamber the 740 semi-auto and the 760 pump-action rifles in the new caliber. It wouldn’t be offered in any of the company’s bolt-actions until three years after its introduction.

To give you an idea of how fruitful of a venture this was, Remington sold far more 740 and 742 rifles in .30-06 than they ever sold in .280, and when it came time to update the model again in the ‘80s (as the 7400), they also offered it chambered for .270 Winchester.

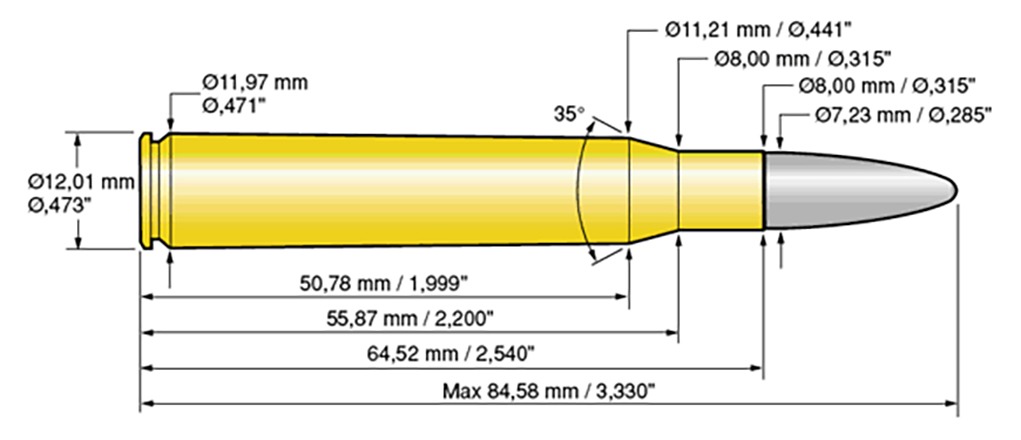

The recipe for .280 was the same as for .270 Winchester, its main competitor, as both cartridges start with a .30-06 as the parent case and neck it down for a smaller bullet, specifically .284 inches for the .280 Rem.

The classic .280 Remington loadings are a 140-grain bullet at 3,000 feet per second and a 150-grain bullet at about 2,900 feet per second. Typical recoil energy is around 17 foot-pounds, about on par with a .308 Winchester or a 150-grain load of .30-06.

However, since the .280 is classically loaded with the middle range of grain weights in .284 caliber, it didn’t benefit hugely from the higher sectional densities and ballistic coefficients of the heavier (160-grain and above) projectiles in factory loads.

Hence it acquired a reputation as a handloader’s darling, as premium high-BC bullets and judicious powder selection gave it stunning effective range with mild recoil, but it just never quite captured serious mainstream appeal.

The rifle and ammo-buying public said to themselves, “Why would I buy that when I can just get a .270 or a 7mm Remington Magnum (when it made its appearance 5 years later)?” and that’s what most of them did.

Midway through its life, Remington rebranded the .280 Remington as the 7mm-06, then the 7mm Express in 1978. All this did was confuse the hell out of the shooting public, who mixed the cartridge up with 7mm Remington Mag. How they expressed this bafflement was by buying different rifles.

The rebranding was over by 1981, and factory ammunition now bears the legendary “Safe For Use With 7mm Remington Express” label to this day. Around the same time, Remington introduced the 7mm-08, which was vastly more successful as a hunting cartridge and in competitive shooting.

In its day, the .280 Remington was known for being a mild-ish hunting cartridge with long legs, perfect for North American game short of the great bears and most African plains game besides the really big ones. It had a reputation of primarily being useful for hunting light to medium game from pronghorn and deer to elk, moose and caribou.

Despite its problems, the cartridge still had some fans. Jack O’Connor’s last rifle was a Ruger 77 action in an Al Biesen stock in .280 Remington.

However, by the 1990s, the damage was done. Long-action cartridges have been falling out of favor since then, and realistically there’s nothing that .280 Rem. does that a .270 doesn’t do equally well in the real world.

.280 Remington Ballistics: Does It Do Anything Better Than .270?

The .280 Remington has an edge over .270 on paper, but it rarely (if ever) materializes in the real world.

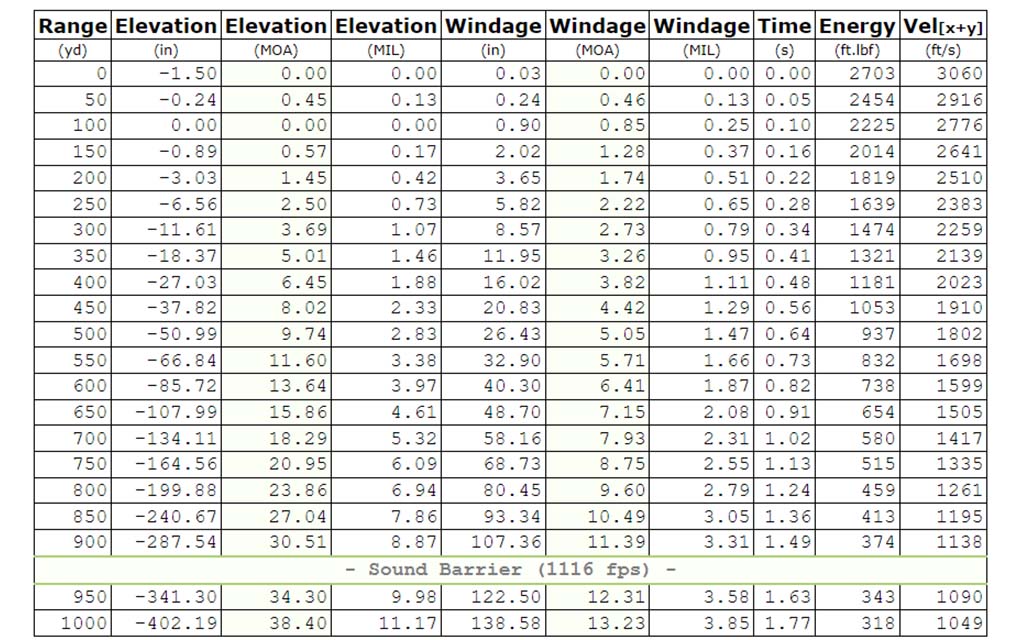

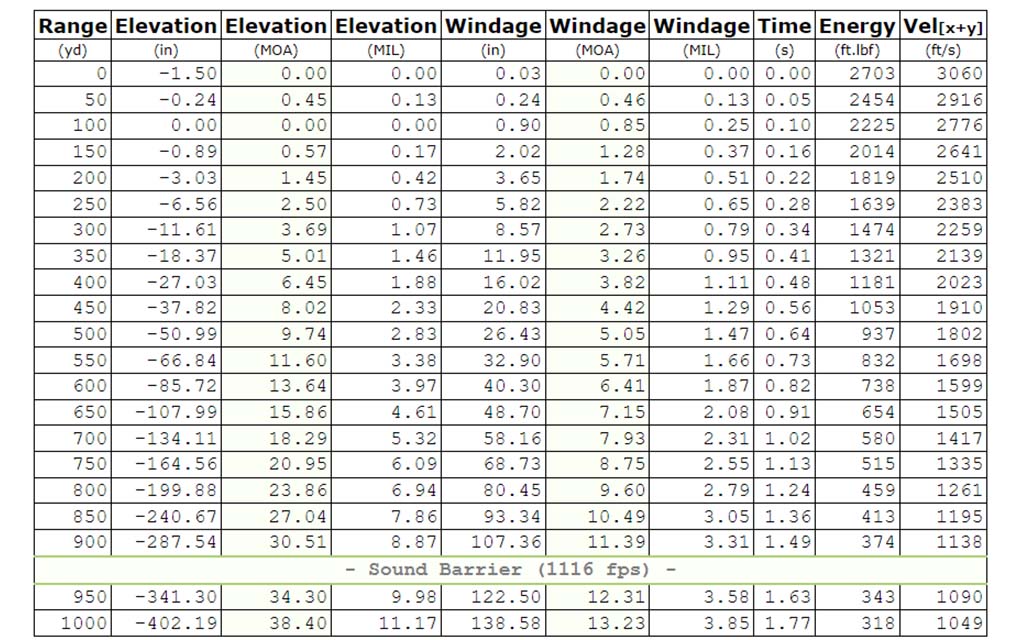

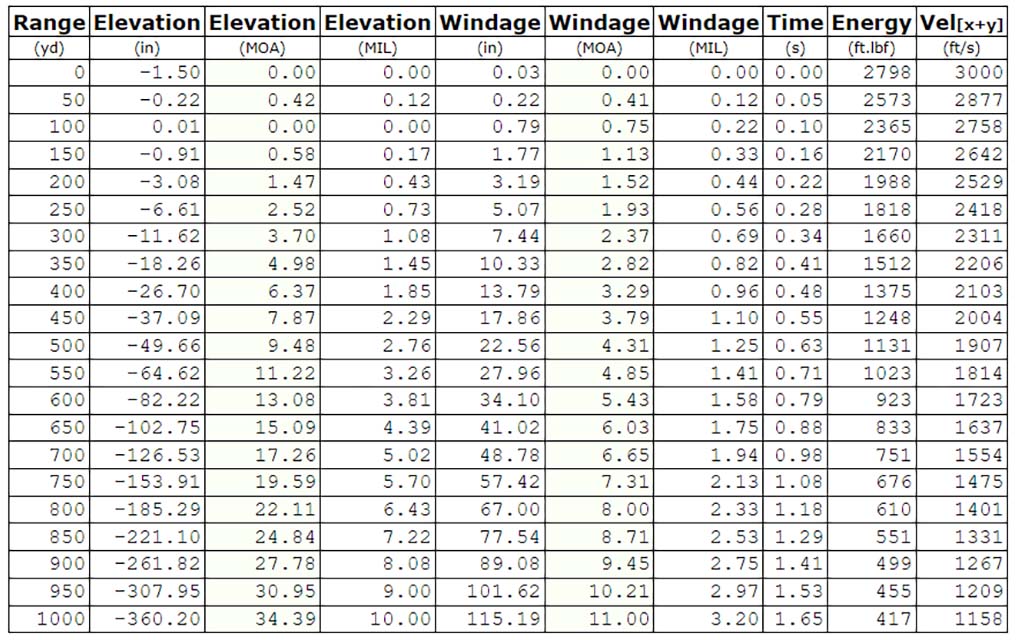

Let’s start by looking at some classic loadings to see how closely they compare using Shooter’s Calculator. All tables were calculated presuming a 1.5-inch sight height, a 10 mph 90-degree crosswind, zero corrections for atmosphere and a 100-yard zero. We’ll begin with 130-grain CoreLokt (G1 BC of .336) in .270 Winchester:

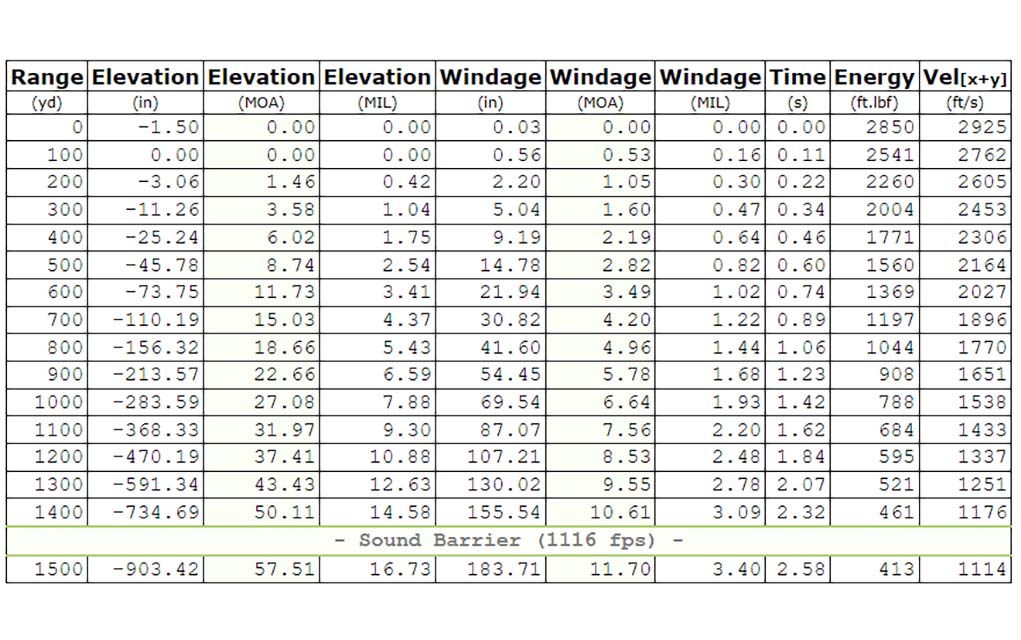

The 130-grain load in .270 is supersonic to over 900 yards and could easily have an effective range on deer to 500 yards. Now let’s look at the 140-grain CoreLokt (G1 BC of .390) load for .280 Remington:

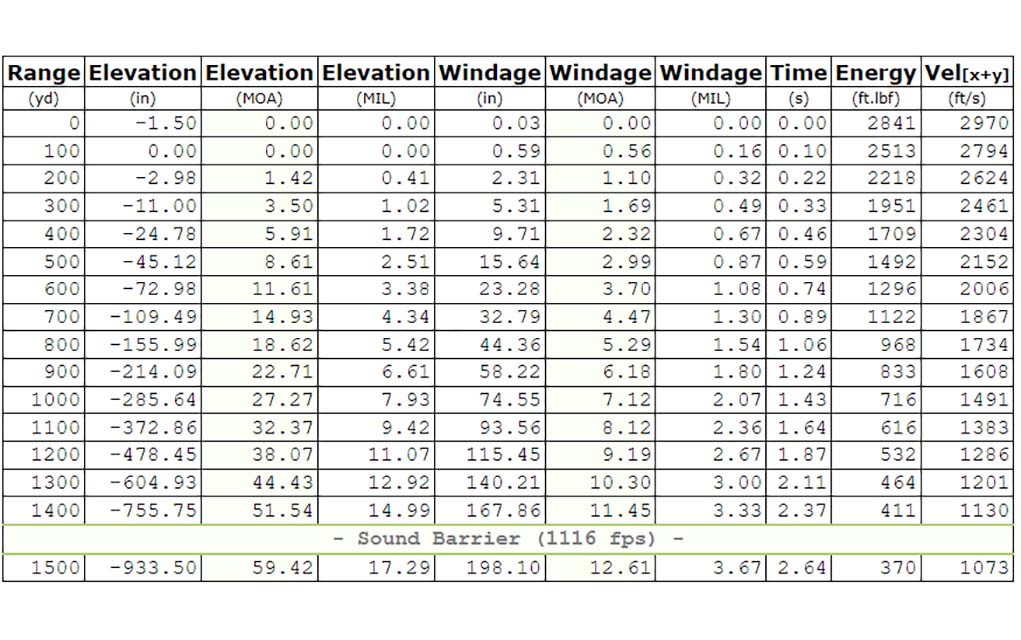

The .280 Remington’s 140-grain bullet is still supersonic at 1,000 yards (though only just) and is well within effective range on light-skinned game up to 650 yards and heavier medium game out to 500 yards.

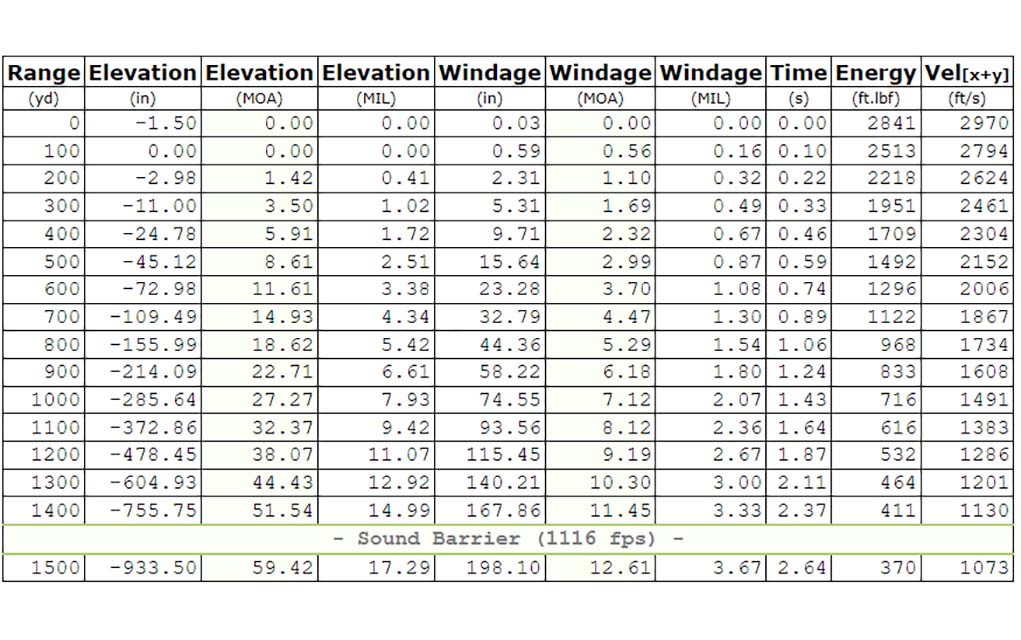

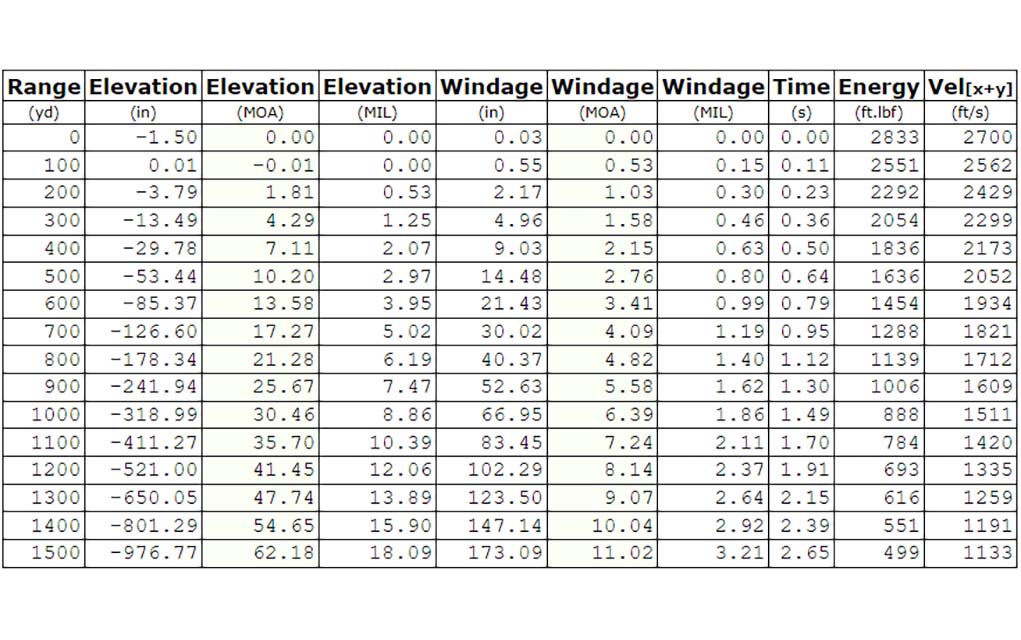

However, both cartridges benefit hugely from modern high-BC bullets. For instance, here’s a trajectory table for .270 Winchester with Hornady’s 145-grain ELD-X (G1 BC of .536) load:

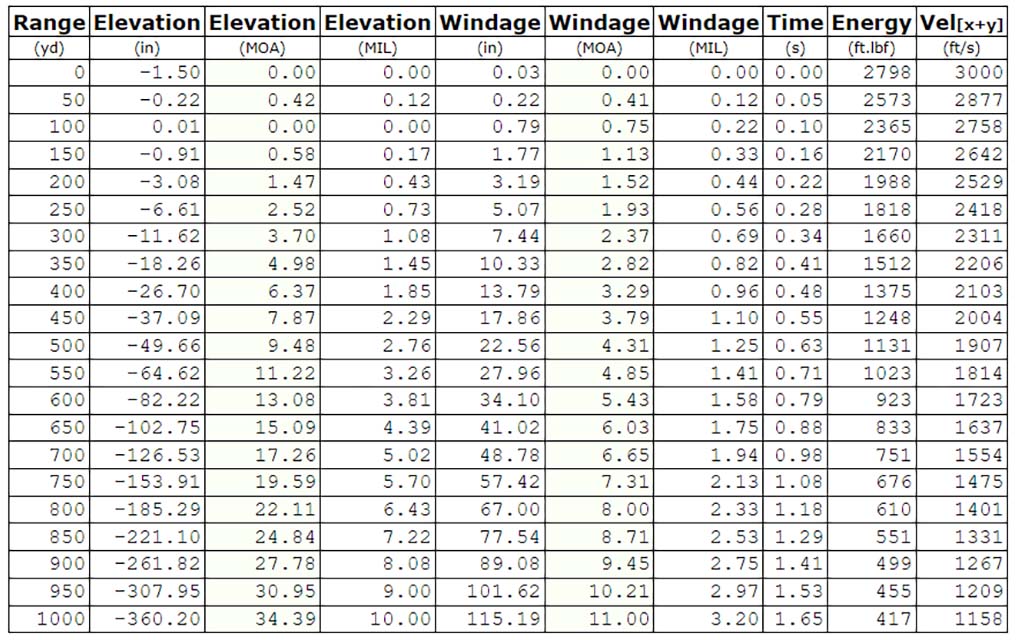

And here’s Hornady’s .280 Remington ELD-X load featuring a 150-grain bullet with a G1 BC of .574:

With modern ammunition, both are excellent at long-range, and both stay supersonic beyond 1,400 yards. The .280 has slightly higher velocity and energy, but at 1,000 yards it only drops 2 inches less than the equivalent .270 load. Not a huge difference practically speaking.

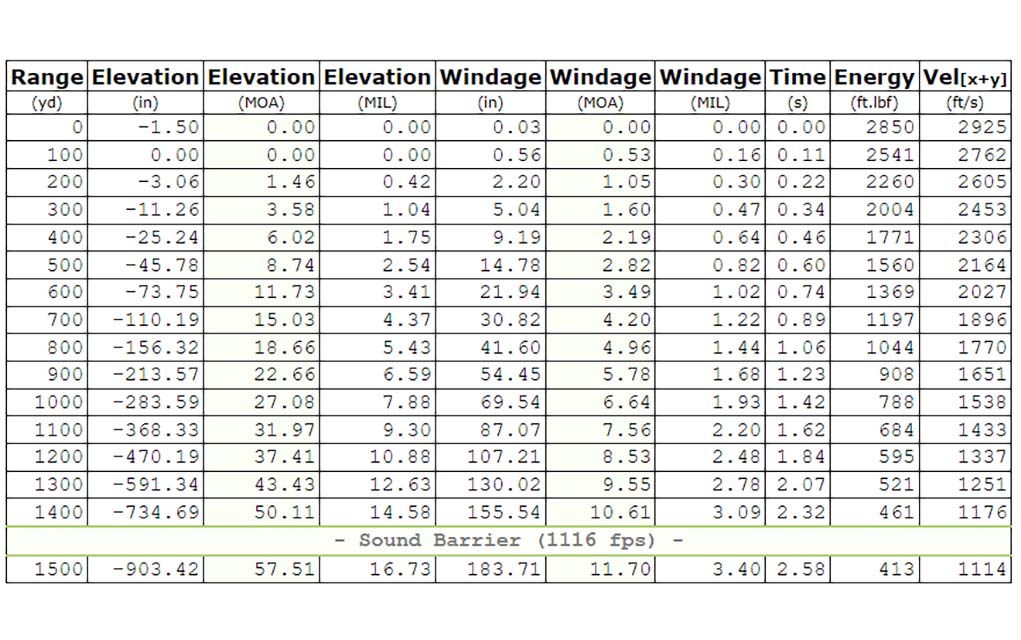

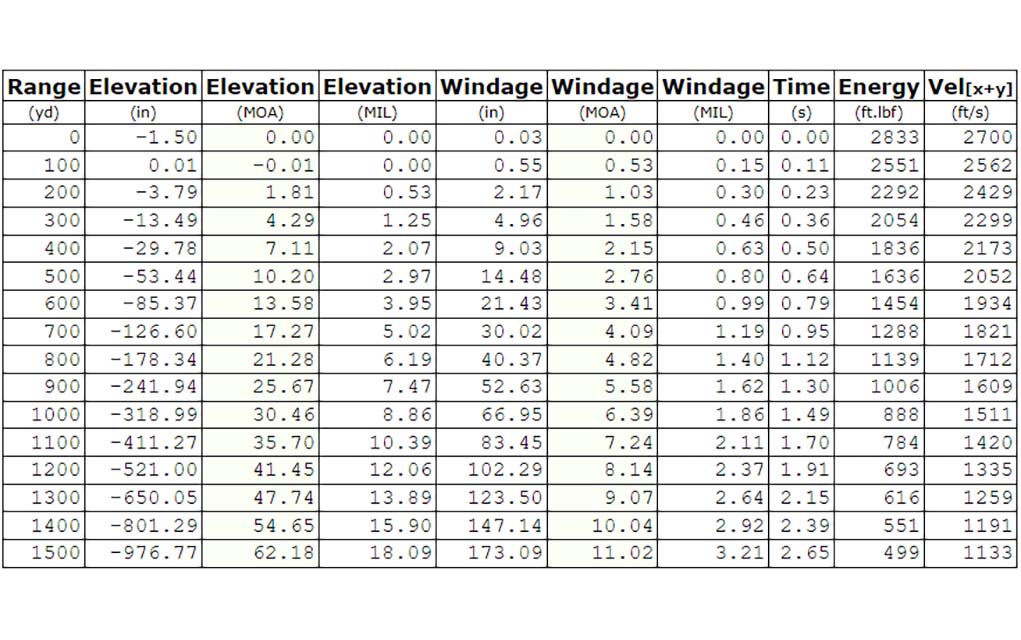

To give you an idea of why .280 Remington is a handloader’s darling, here’s a trajectory table based on Nosler’s load data using a 175-grain AccuBond LR bullet (G1 BC of .648) at 2,700 fps:

As you can see, it’s still supersonic at 1,500 yards, and that’s a feat that even many loads of 6.5mm Creedmoor can’t achieve. Scrupulously handloaded, it’s a long-range hunter’s dream…but few people have the time, money or patience to work up a load like that.

As far as factory ammunition goes there’s a difference between .270 Winchester and .280 Remington, but there’s more to cartridge selection than what ballistic data can tell you.

The reality is that a deer or elk can’t tell what velocity the bullet is traveling at when it hits them. No animal anywhere has decided “If it had been 100 fps faster, I’d actually die!” With the CoreLokt loads, there’s only a 100-fps difference at 500 yards (a discrepancy of less than 10 percent) and the .270’s bullet has only dropped an additional 1.3 inches. At the ranges you’d likely use either of these cartridges at, the differences are too small to matter, essentially making them identical in the field.

An attempt was made to better the .280 when P.O. Ackley created .280 Ackley Improved, but it was so close to 7mm Remington Magnum in every respect (including recoil) that it never really caught on either.

.280 Remington Vs. .270 Winchester In The Real World

So, ballistic differences aside, let’s discuss other aspects of the .280 Remington versus .270 Winchester debate.

At the time of this writing, on GrabAGun, there are 146 rifles chambered in .270 Winchester, over 100 of which are in stock. Meanwhile, there are 3 in .280 Remington, none of which are in stock.

As for ammo, GrabAGun lists 11 loadings in .280 Remington, 3 of which are in stock, compared to 70 listings of .270 Winchester of which 43 are available. Savage Arms, oddly enough, makes 10 in .280 Ackley, but none in the original recipe. Further, the prices are just as bad as the availability of .280 Rem., as Ammoseek currently lists the cheapest .270 Winchester at about 75 cents per round while the cheapest .280 is almost $1.50 per round.

Is .280 Remington Even Worth Fooling With Anymore?

For the new shooter looking to get into a serious hunting rifle, you’re better off staying away from .280 Remington.

Not because there’s anything inherently wrong with it, of course, and as mentioned it can have excellent performance with handloads. But when you consider the price and availability of .280 rifles and ammo alongside the fact that there are much more accessible cartridges with equal or better performance, the choice becomes obvious.

Outside of inheriting a .280 Remington rifle or finding a cool one for sale at a price you can’t refuse, there’s no real reason to get into the cartridge today. If you do happen to have one and are looking to use it, I’d recommend the 140-grain CoreLokt or Federal Fusion loads for hunting deer-sized game in the western states and the Hornady Precision Hunter 150-grain ELD-X for larger game or hunting at longer ranges.

Raise Your Ammo IQ:

Read the full article here