There was a time when some Americans sought adventure in foreign lands and often took up arms and fought as foreign volunteers. While essentially soldiers of fortune, many were driven by ideology more than profit.

That was true of the aviators who volunteered to serve in the Escadrille Américaine — later renamed the La Fayette Escadrille in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolutionary War. The unit’s exploits during World War I attracted worldwide attention and encouraged other Americans to become interested in flying for France. Though more than 200 Americans eventually were trained by France to be flyers, most were assigned individually, or in twos or threes, to various French Aviation units.

A generation later, hundreds — perhaps even thousands — of American citizens volunteered to fly with the Royal Air Force (RAF) before the United States officially entered the war in December 1941. The most famous were the Eagle Squadrons. However, it was halfway around the world that another unit was organized in early 1941 and became almost legendary — it was the American Volunteer Group (AVG), more commonly known today as the “Flying Tigers.”

Origins of the AVG

Though Americans had flown for foreign powers previously, the idea for the foreign flying unit began when Soong Mei-ling (AKA Madame Chiang), wife of the Chinese Nationalist ruler Chiang Kai-shek, was named to head the Chinese Aeronautical Commission. She quickly noted the inferior nature of the planes that comprised the Chinese Air Force and made a proposal to Claire L. Chennault, then a captain in the United States Army Air Corps, to help organize a unit of trained pilots.

Chennault, who suffered from chronic bronchitis, blood pressure fluctuations and chronic exhaustion — the result of years in the cockpit flying at high speeds — was also known for his disputes with superiors. After being passed over for a promotion and grounded, he resigned from the military in April 1937. As a civilian, he was soon recruited to go to China, where he joined a small but determined group of American aviators training Chinese pilots. The clouds of war with an increasingly militaristic Japan were on the horizon, and Chennault sought to do his part.

He accepted a three-month assignment to survey the Chinese Air Force and to make recommendations on how it could be improved. That short “hitch” in China would eventually last eight years! But he didn’t serve alone, far from it, in fact.

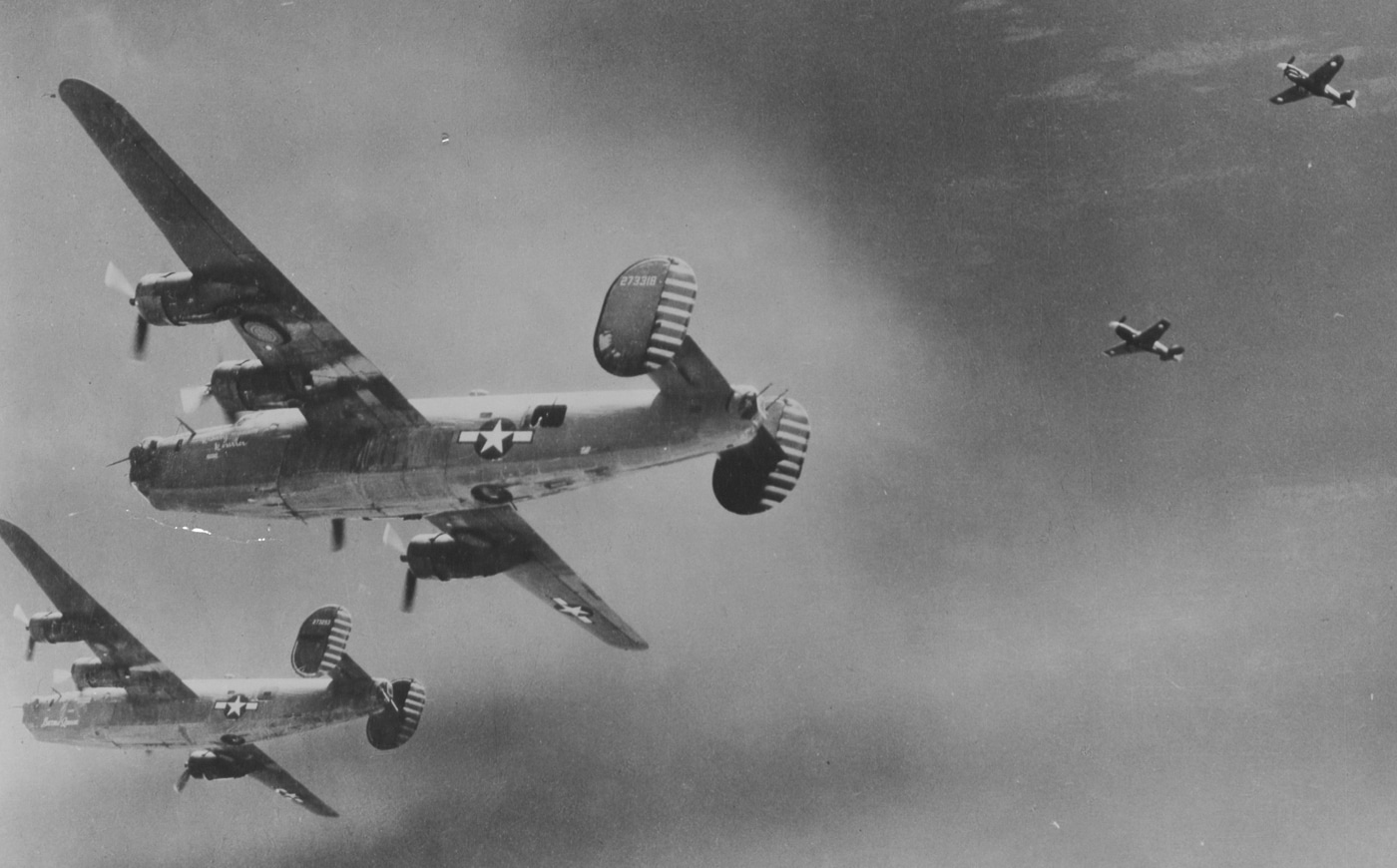

Beginning in the late spring and early summer of 1941, Chennault recruited American pilots and ground crewmen to fly and maintain 100 Curtis P-40 Warhawk fighters that the Chinese Nationalist government was able to purchase from the United States.

The P-40 was truly America’s state-of-the-art fighter prior to World War II. It had a maximum speed of 362 mph and a cruising speed of 235 mph, with a range of 850 miles without refueling. More importantly, it was a rugged and reliable aircraft — perfect for the AVG, which lacked the support of the U.S. military.

Contracts to serve in China were issued through CAMCO — the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company — which served as China’s “agent” for handling the purchase of the aircraft and the hiring of personnel. The reported salaries ranged from $250 to $750 per month based on experience, plus travel and allowances. The pay was more than almost any military aviator earned at the time. Also included were housing and 30 days’ paid leave, while a $500 bonus was offered to pilots for each enemy aircraft shot down. Those bonuses were later extended to include enemy planes destroyed on the ground.

Ideology may have been a factor for the American aviators, but the pay certainly didn’t hurt, especially as the United States was still recovering from the Great Depression.

The AVG Volunteers

In all, 109 pilots and 109 ground crew personnel were recruited, and Chennault’s AVG volunteers began training in Burma in July 1941. The majority of the pilots came from the U.S. Navy, while a large number were from the U.S. Army Air Corps and a handful more from the United States Marine Corps. Around a dozen of them were also Chinese Americans.

It should be noted, despite what movies and TV shows may have suggested, these weren’t battle-hardened men — and few had flown in combat.

However, Chennault proved to be a perfect leader for these soldiers of fortune. He taught the American aviators tactical methods, which included 72 classroom hours and 60 flying hours. His instruction called for the pilots to attack in pairs and to rely on the P-40’s main attributes, which consisted of sturdiness, firepower and diving power.

The classroom lectures included simple and easy-to-remember diagrams of Japanese aircraft — highlighting the vulnerable points. According to some sources, AVG members would later recall finding themselves attacking and instinctively firing accurately at vulnerable points as a result of the training they received. Essentially, Chennault’s training was to ensure that his fliers would “make a pass, shoot, and break away.”

The training was rigorous and dangerous. Three pilots died, while multiple planes and other equipment were damaged in various accidents.

Yet, by November 1941, the pilots were trained and most of the P-40s had arrived in Asia. The Flying Tigers were subsequently divided into three squadrons: 1st Squadron (“Adam & Eves”); 2nd Squadron (“Panda Bears”) and 3rd Squadron (“Hell’s Angels”).

Combat Operations

Another common misconception about the Flying Tigers is that they took part in combat operations before America entered into the Second World War, but in fact, the first action took place on December 20, 1941 — 13 days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

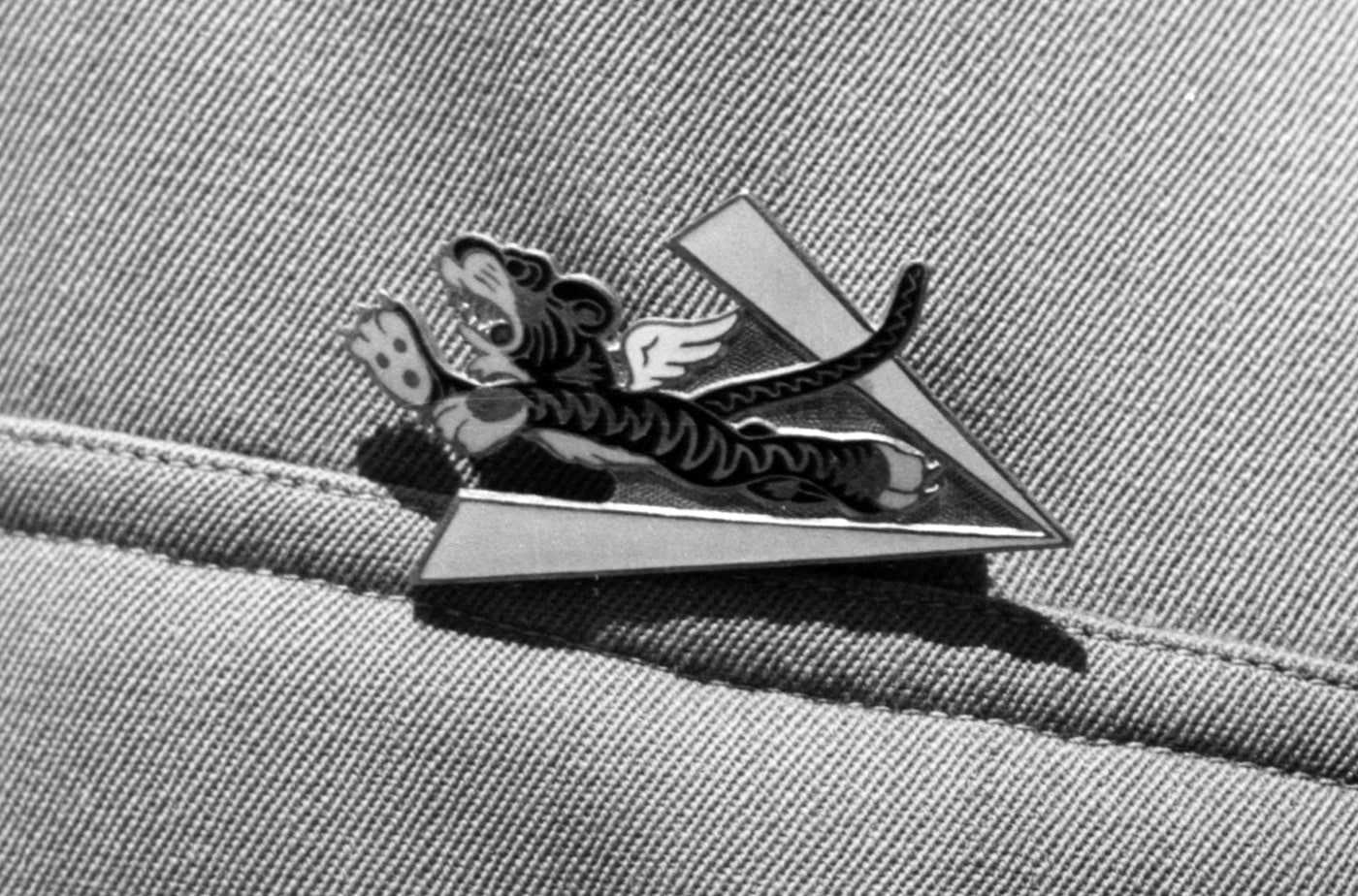

The unit, based at Kunming, China, was alerted to Japanese Mitsubishi K1-21 twin-engine bombers that were approaching from Hanoi, escorted by Japanese Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters. Chennault scrambled two squadrons and deployed them into the air. The P-40s were quite ferocious looking as his pilots had painted a shark’s mouth and teeth on the front of the fighter. The aviators tore into the A6Ms.

Thanks to their superior diving speed and maneuverability, the P-40s successfully shot down nine bombers out of a 10-bomber force. The lone Japanese bomber reportedly barely made it back to its base in Hanoi — then part of Japanese-controlled French Indochina. The sortie highlighted the capabilities of the AVG, but it was a personal victory for Chennault.

The Chinese were so grateful to Chennault and the aviators that they nicknamed the unit “Fei Hou” — or “Flying Tigers.” The name quickly stuck.

However, subsequent encounters with the Japanese proved that the AVG was facing an adversary that could adapt quickly. When the Americans tried attacking another group of Japanese bombers, the Japanese broke formation and turned to take the attack to the AVG pilots. Fortunately, the Flying Tigers had faster and more maneuverable aircraft. More importantly, they were better trained.

Even as the Japanese adapted, the Americans responded just as quickly. That resulted in victory after victory against the Japanese Air Force.

That proved to be vital. Perhaps the most important service performed by the Flying Tigers in the early months of 1942 was that the unit was scoring the only American victories anywhere in the world. Chennault also became the first American military leader to be publicly recognized for striking a blow against the Japanese.

It should be added too that the unsung heroes were the Chinese laborers who built the AVG’s runways by hand. They did so without modern tools and in many cases with no tools at all — literally using their bare hands to dig the runways for the American aviators.

Short-Lived Unit

While the Flying Tigers’ contribution to the war effort can’t be overstated, it only operated from December 1941 to July 1942. During that time Burma was of vital importance to China’s war efforts, but Japan had sealed off China’s coast from supply lines, and the Nationalist forces depended on supplies coming in from the port of Rangoon over the mountainous Burma Road to Kunming.

The Flying Tigers ensured that the road remained open.

Yet, when the United States entered the war, the American military presence in the Pacific Theater was dramatically increased, and that included the American troops assigned to China.

Lt. General Joseph W. Stilwell pressured Chennault into integrating the Flying Tigers into the U.S. Army Air Forces, but initially, the unit was to be under the command of Brigadier General Clayton Bissel. The Flying Tigers were particularly devoted to their leader and made it clear they didn’t want to be absorbed into the U.S. military without that leader. The unit was disbanded and a few of its members joined Chennault in a regular army unit called the China Air Task Force.

Chennault rejoined the U.S. military as a major in April 1942, only to be promoted to colonel three days later, and then 12 days after that he was promoted to brigadier general.

In March 1943, the Task Force became the nucleus of the new 14th Air Force — and their supplies had to be flown in over “the Hump,” the dangerous 500-mile air route from India to China over the Himalayas. Despite supply problems, the 14th Air Force grew from fewer than 200 aircraft to more than 700 planes by the end of the war. Its aviators in China destroyed and damaged more than 4,000 Japanese aircraft during the war, sank more than a million tons of shipping, and destroyed hundreds of locomotives, trucks and bridges while helping to defeat the Japanese in China.

“Japan can be defeated in China,” proclaimed Brig. Gen. Claire Chennault, according to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, which now honors the Flying Tigers with a surviving P-40 Warhawk in its collection. “It can be defeated by an Air Force so small that in other theaters it would be called ridiculous. I am confident that, given real authority in command of such an Air Force, I can cause the collapse of Japan.”

The Flying Tigers in Pop Culture

Though the exploits of the American Volunteer Group were rather short-lived, its story has become beyond legendary. The film Flying Tigers was released in October 1942 starring John Wayne and John Carroll, while several other motion pictures released during World War II further shared the exploits of the unit — with a significant number of historical liberties.

The TV series Black Sheep Squadron from the 1970s didn’t focus on the AVG, but it did highlight the wartime role of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, who served in the Flying Tigers and later commanded Marine Fighter Squadron 214 (VMF-214) flying the F4U Corsair. The short-lived Tales of the Gold Monkey offered a heavily fictionalized take on the unit — notably suggesting it was engaged in the Pacific against the Japanese years earlier than reality.

Though the last surviving member of the original AVG, Frank Losonsky, died in February 2020, the Flying Tigers won’t be soon forgotten. There are now multiple memorials and museum exhibits dedicated to the Flying Tigers in China, the U.S., Taiwan and Thailand. The history of the unit will live on, like all good legends.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here