World War I forever changed the way wars would be fought. In 1914, man had only recently taken to the skies in fragile aircraft, aloft with a small engine surrounded by just wood and canvas. Many of those early “kites” were often as dangerous to their pilots as they were to any prospective opponent.

Still, it didn’t take long for the gentlemanly waves and salutes between unarmed opposing pilots to give way to dropping rocks and bricks, dangling grappling hooks, and then trading pistol shots and shotgun blasts. No sooner had one man taken flight than another was committed to shooting him out of the sky. The stage was set for an aerial arms race.

Toward the Future

After the Wright Brothers successful flight, interest in aeronautics grew rapidly in the United States. Various flying clubs staged events to advance flying beyond the level of a hobby, and also to attract the interest of the American military.

In August 1910, 300 feet above the Sheepshead Bay racetrack on Long Island, New York, U.S. Army Second Lieutenant Jacob Fickel clutched a wing strut of an early pusher aircraft (piloted by aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss) and fired four shots from a Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifle at a target below. The first recorded firing of a firearm from an aircraft yielded surprisingly good results: two of Fickel’s shots were in the bullseye.

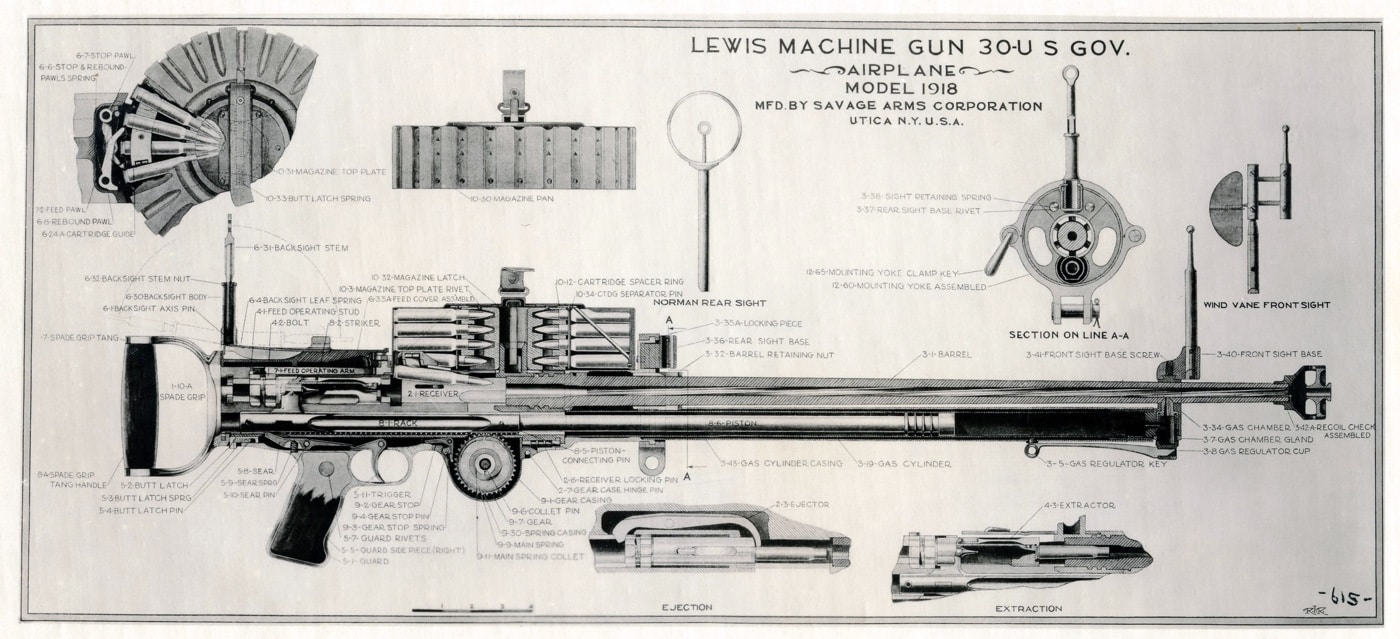

In August 1912, America witnessed another first in military aviation. U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Isaac N. Lewis had recently created a new machine gun for the Automatic Arms Company of Buffalo, New York. Colonel Lewis’ gun was a modern design, much lighter than most of the era, and fed by a detachable drum magazine. Lewis was a dynamic thinker, and shortly after he produced the first few examples of his now-famous gun, he envisioned using the 25-lb. weapon from an aircraft.

At the U.S. Army’s Pilot Training School at College Park, Maryland, Lewis’ plan came to fruition. The school Commandant, Captain DeForest Chandler, offered to perform the airborne Lewis gun demonstration personally.

[For more information, be sure to read Peter Suciu’s article on the Lewis gun.]

After a short training class from Lewis on how to handle the gun, Captain Chandler boarded a Type B Wright pusher aircraft, with Lieutenant T. DeWitt Milling serving as pilot. The Lewis gun was strapped in between his legs, with the muzzle resting on the top of the aircraft’s foot-rest crossbar. A 6×7’ target made of cheesecloth was placed on some open ground near the rear of the hangar.

Three passes were made from about 250 feet, with Captain Chandler firing a short burst each time. Chandler had no sight and could not see the impact of his rounds. Even so, it was discovered that he hit the target five times, with several strikes very close by. The next day, they tried it again (with Lt. Roy Kirkland piloting) and were rewarded with even better results: 14 hits out of 44 shots fired. Suddenly, the aircraft and the machine gun were forever joined.

Rising Up

While much of the Great War ground combat became mired in bloody stalemate, the combatant air forces sought to get infantry machine guns out of the trenches and into the skies. It would not be easy.

Machine guns themselves were relatively new, and supplies remained limited while war industries on both sides struggled to produce them in quantity. Meanwhile, the concept of a “light” machine gun was essentially unheard of. At a time when the tiny, fragile aircraft of the era needed compact firepower, most machine guns weighed in at more than 40 lbs., even without ammunition.

Most of the infantry machine guns of WWI were water-cooled, their hefty water jackets providing them with tremendous extended firing capability without overheating the barrel. But the heavy, belt-fed infantry machine guns had not been designed with the needs of airmen in mind. Aircrews had few worries about overheated barrels, as the ambient temperatures at altitude were often coolant enough, with the continuous airflow also a cooling factor.

At first, many of the standard infantry guns were modified by draining the water and perforating the jacket to allow the barrel to be cooled by the airflow. But guns like the Vickers machine gun or the German MG08 were belt-fed, and the early combat aircraft had little capacity for ammunition storage. Before the invention of reliable synchronization gear, the observer in the rear cockpit was the primary gunner. Most of the converted infantry guns were not workable solutions for the rear gunner.

Proper air-cooled machine guns were sought out for aerial use, but they were in incredibly short supply — so much so that a few hardy Frenchmen even tried to use the strip-fed Hotchkiss Mle 1914 (weighing 52 lbs. for the gun itself) aloft.

On the other hand, the Lewis was ready to take off.

Enter the Lewis

When World War I began, the Lewis gun was already being manufactured, albeit in small amounts, in England. Strangely, the attitude of the British War Office towards the Lewis in 1914 was that it was only fit for use in aircraft. There was little urgency shown in its production either, as by the summer of 1915 the Royal Flying Corps had fewer than 300 Lewis guns available.

In 1915, the basis British “air gun”, the Lewis Mk. I, became the standard light machine gun of the British Army. At that time, both air and ground Lewis guns used a wooden shoulder stock, the large radiator casing, 47-round pan magazine and the same adjustable tangent sight. However, British air crews were busy modifying the Lewis (essentially against regulations) to reduce weight and improve its usefulness in the air. While production of the Lewis ramped up significantly for the Army, the Royal Flying Corps found itself begging to obtain the guns originally allocated to them.

In 1916, the RFC received the Lewis Mk. II, an aircraft variant that standardized their earlier modifications — lightened by significantly reducing the radiator housing, swapping a spade grip for the shoulder stock and gaining a more effective aerial sight. The 47-round pan magazine would be upgraded with a 97-round drum made specifically for aircraft use.

With those changes, the Lewis gun became the most versatile aircraft gun of World War I. Lewis Guns would be made at BSA in England (.303), Savage Arms in the USA (.30 caliber), and about 3,000 were made in France by Darne (.303).

Offensive and Defensive Mounts

The Lewis gun gained great popularity in all the Allied air forces due to its tremendous versatility. It could be mounted for use as a forward-firing weapon operated by the pilot, or as a defensive gun fired by an observer or gunner.

In the early war period, Lewis guns were used as forward-firing armament in “pusher-type” aircraft with rear-mounted engines. The open front nacelle of a pusher aircraft offered the pilot or gunner a completely unrestricted field of fire.

Before the invention of effective synchronization gear to allow a machine gun to fire safely through the propeller arc, the Lewis gun provided a solution for “tractor-type” aircraft with the propeller in the front. The early mounts for tractor types used a Lewis pointing forward at an angle to fire just outside the spinning propeller. Unfortunately, this proved to be awkward.

The next innovation was to mount a Lewis gun on the top wing to fire forward above the propeller. This finally gave many aircraft types an effective offensive capability — albeit one that strained the pilot’s abilities to the extreme. Reloading the magazine on a Lewis gun while flying and fighting required great coordination and cool nerves. Later mounts for the top wing, like the British Foster, allowed the pilot to remain seated while he retracted the Lewis to face level to reload.

Some pilots learned the complicated technique of firing the Lewis forward and upward at an angle — quite useful in an “up and under” attack on an enemy, particularly those with a rear gunner. Lewis guns were also a good addition for fighter aircraft with little space in front of the pilot, providing supplemental firepower in aircraft like the SE5a and the Nieuport 17, or the only practical armament for a tiny ship like the Nieuport 11.

For the observer/gunner, the Lewis Gun was the best “flexible” weapon of the first air war. Compared with any other aerial gun, the Lewis was the most potent and the easiest to reload in flight. The 97-round drum offered a reasonable ammunition load for the time, and the cyclic rate was sufficient.

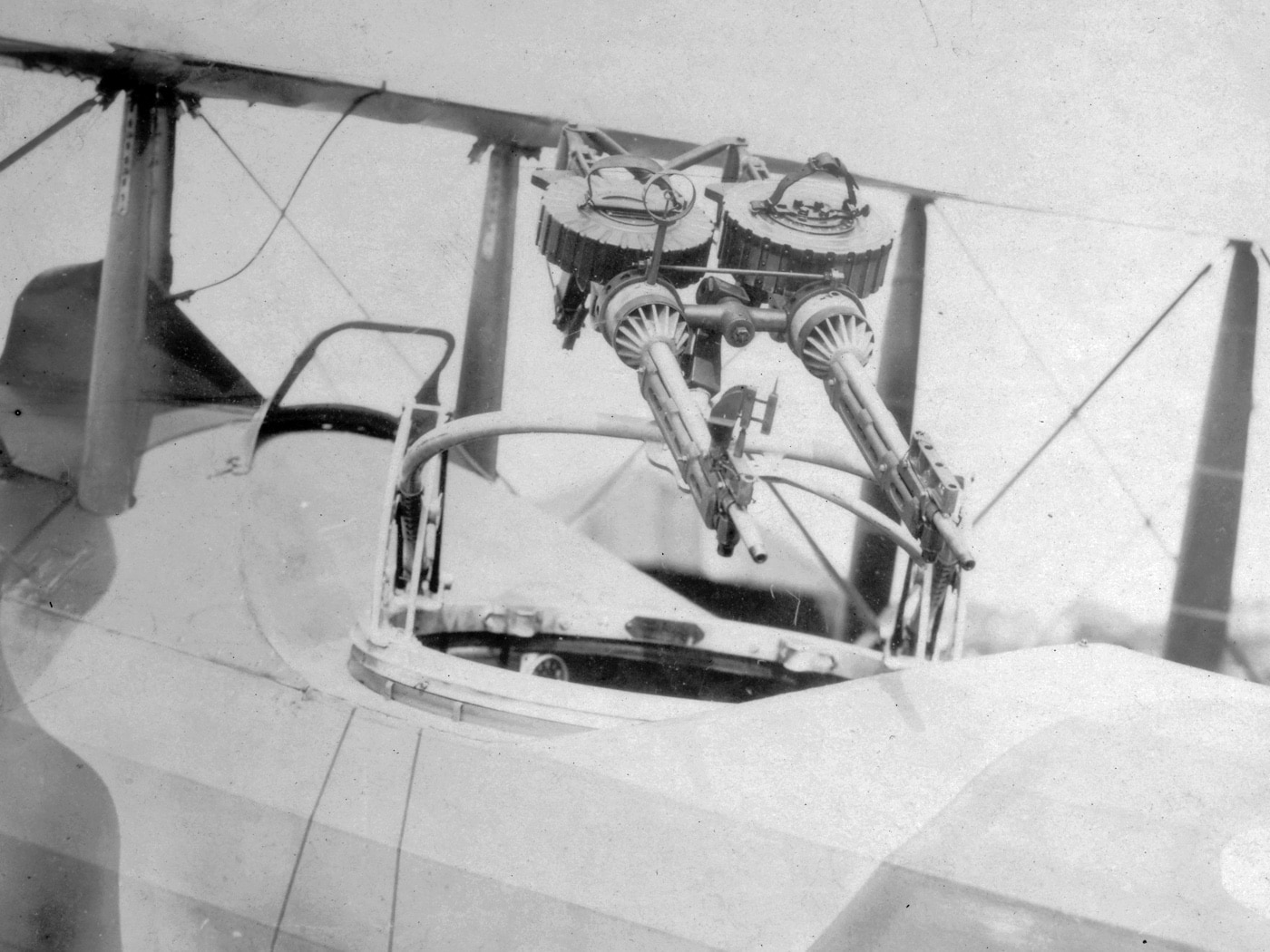

As the war progressed, Lewis gun mounts for observers became more sophisticated, and by 1918 many French and British observers had the option to use twin-Lewis mounts. The two-gun arrangement proved to be rather heavy and difficult to maneuver, and many observers chose to stick with just one gun for greater efficiency. Some American experiments arrived in Europe in time to see combat, including a useful muzzle brake as well as the “Hazelton Device,” a muzzle booster that increased the cyclic rate to more than 800 rounds per minute.

In a testament to its abilities, every Allied air force in Europe used the Lewis gun. Even the Germans used them, often equipping their observers with a captured Lewis when there was enough ammunition and magazines available.

The Lewis and the Scarff Mount

The US Army Air Forces Historical Study “Development of Aircraft Gun Turrets in the AAF, 1917-1944” outlined the difficulties of the observer/gunner in World War I, even when using the advanced (for the era) Scarff mount:

The earliest WWI turrets usually consisted of circular plywood tracks slotted to carry forked machine-gun adapters riding on hardwood casters. They were cumbersome and unmanageable as the wood warped and bound with every flexing of the aircraft fuselage: and manipulation, even at the laggard air speeds of that day, was complicated by the fact that the gunner never had enough hands to perform the many operations involved in training his guns. The major objection to these early turrets, however, grew out of the difficulties encountered in bringing guns to bear on elusive aerial targets, attacks from above left the gunner kneeling in his cockpit, while attacks from below found him climbing to his seat to sight over the plane’s edge

The Scarff mount, with its adjustable elevation attachment counterbalanced by elastic shock cord and its backrest rotation assistor, overcame many of these difficulties. By the end of the war Allied aircraft were using twin Lewis guns in Scarff rings perfected sufficiently to permit firing a single off-center gun without adverse slewing effect, and French manufacturers were turning out machined-aluminum turrets differentiated in type between nose and tail. But even these technical advances were recognized as unsatisfactory at the time of the Armistice, and commentators summing up the lessons of the war were specific in their warnings to the future. Officers with war experience repeatedly stressed two imperative requirements: first, to devise some means for overcoming the effects of high-speed slipstreams upon flexible guns and second, to perfect a satisfactory method of covering the lower quarter sphere behind the tail with protective gunfire.

The Conundrum

While the Lewis gun was a fine weapon, there were still many lessons to be learned before the average observer/rear gunner could use it well enough to defend his aircraft. The British and French set out to solve the problem with advanced training.

In the Royal Flying Corps’ textbook of Aerial Gunnery (1917), the manual states:

Difficulty of taking steady aim in the air: Experience has shown that a gunner firing from an aeroplane cannot hold his gun very steadily upon a mark which is passing him, but that, even after considerable practice, he will as a rule scatter his bullets over a wide area around that mark. This is principally due to two distinct causes — the difficulty of traversing a gun steadily to follow a moving object, and to small angular movements of the aeroplane, due to unsteadiness of the air.

As to the question of practical range, the textbook advises:

Range at which to open fire: The maximum range at which fire may be profitably opened must depend very largely on individual skill, and on such circumstances as the relative speed and aspect of the two aeroplanes. It is impossible at present to lay down anything very definite on this point, nor will it be possible until experience has been gained of the actual results obtained with the new pattern sights by men thoroughly trained in their use. Sufficient information has been obtained, however, to show that under some circumstances fire may be opened with advantage at 300 yards, but that range should rarely, if ever, be exceeded. On the other hand, at ranges of 100 yards or less the relative position of the aeroplane may be changing so rapidly that the average man cannot use his sights with any effect but must rely on maneuver and tracer bullets. For the present, therefore, observer pupils should be taught to reserve all fire to within 300 yards and to try to get in as much as possible at about 200 yards.

An American postwar evaluation of aerial gunner concluded:

The idea that a fighting airplane should be regarded mainly as a moving platform for a machine gun has been fully demonstrated, and it is hardly too much to say that the length of a pilot’s life at the front is directly proportional to his and his observer’s ability to shoot.

As for the Lewis Gun itself, the normal rate of fire was about 550 rounds per minute, with the rounds accurate (on the ground) out to 800 yards. Accuracy in the air was anyone’s guess — experience and continuous training made the biggest difference.

Canvas Wings. Iron Men.

The air war in World War I has often been characterized as romantic, or even chivalrous. In reality, it was none of those things — it was an unrelenting, unforgiving struggle with few chances to succeed — let alone survive.

Allied airmen climbed into fragile aircraft that most of us would not even taxi in today. They fought almost exclusively without parachutes, and fought without protection against the elements, fire, gunshots or flak. Everything they learned, from training techniques to combat tactics was improvised, literally, on the fly.

Into this maelstrom, many of these men went with the most important — and capable — aerial weapon of the Great War — the Lewis gun.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here