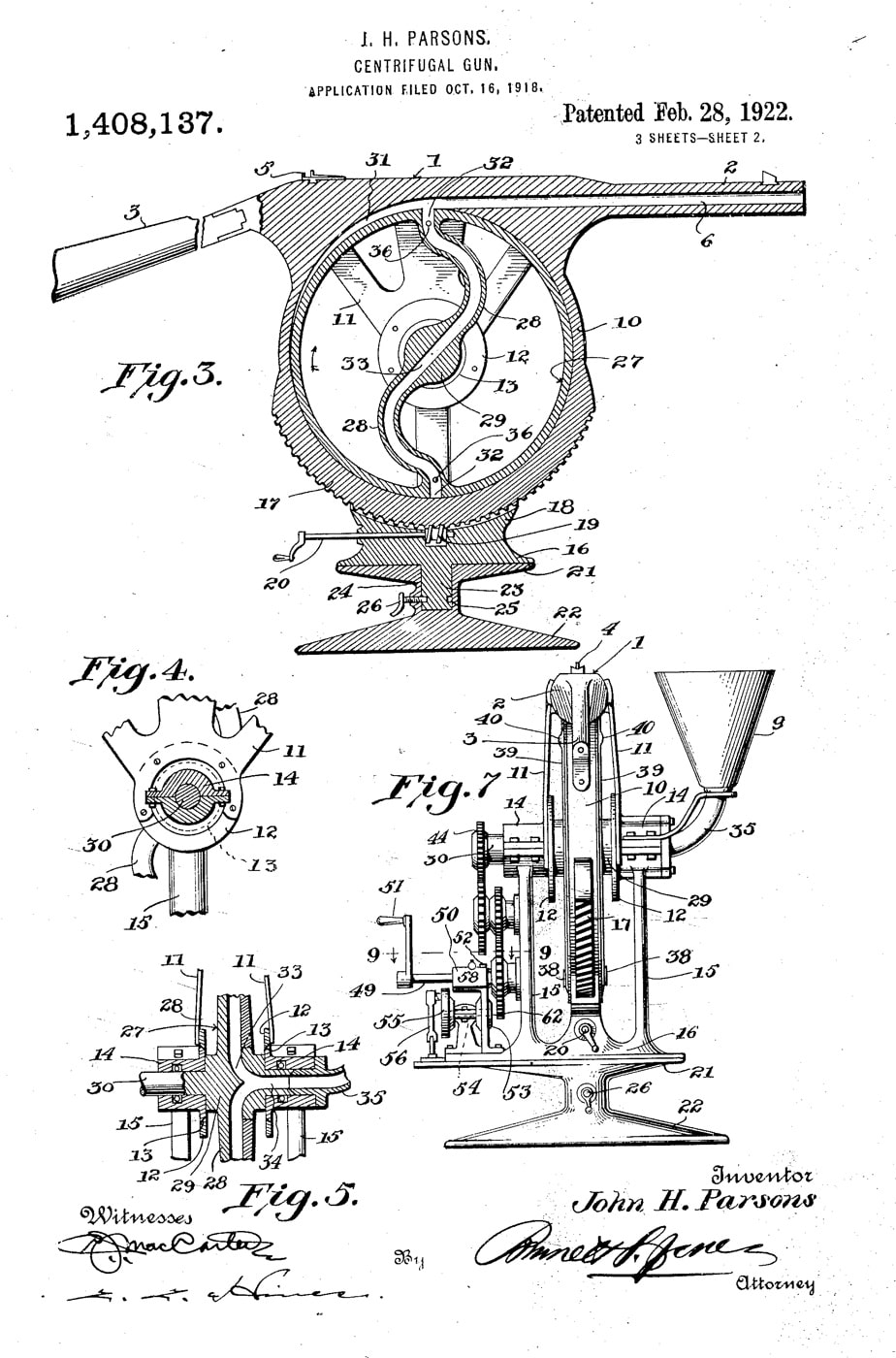

Since the American Civil War, a handful of weapons developers have sought to turn the unique powers of the centrifuge into a rapid-fire weapon. These are not firearms, of course, as no gunpowder is used. The driving force of exploding powder is replaced by a disc rotating at extremely high speed, designed to grab and fling the projectiles downrange.

During the Civil War, the concept of the centrifugal gun took shape. Variations in design ranged from hand-cranked to steam-powered, varying in caliber from .58-caliber musket balls to 12-pound cannon balls. Boston-based designer Robert McCarty got some traction with his hand-cranked, musket ball-flinging device, which even secured a demonstration for President Lincoln. However, no one was impressed enough to send McCarty’s weapon to the field for a combat test.

A Strange Journey

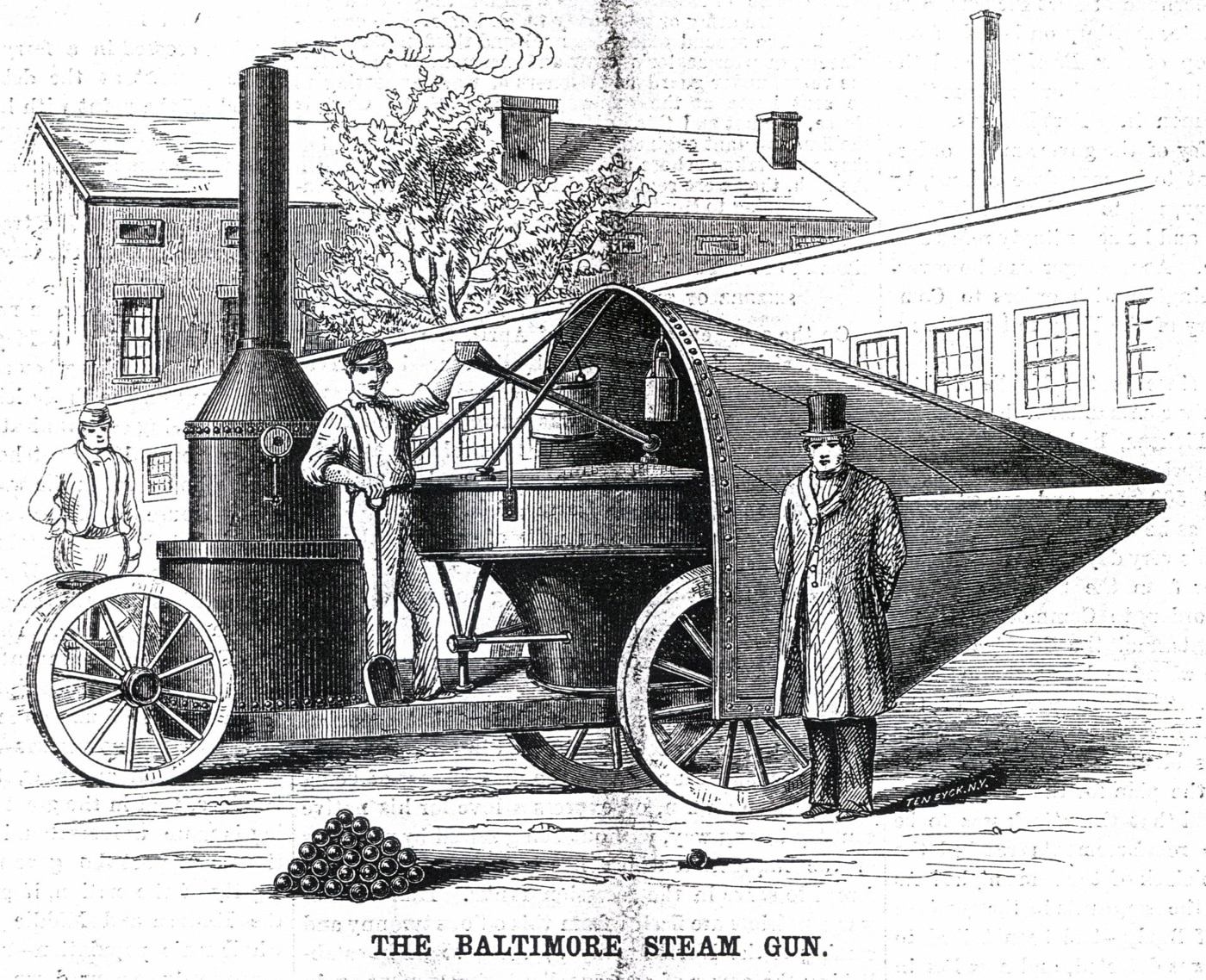

Inventor Charles S. Dickinson had been working to harness the powers of centrifugal force to create a rapid-fire weapon beginning in 1858. His first efforts were hand-cranked. By early 1861, Dickinson had constructed a large, steam-powered contraption with the help of some Boston-based inventors.

In February of that year, he had traveled to Maryland and demonstrated his potential weapon of mass destruction to the Baltimore City Council. The Baltimore police were impressed enough to take the monstrosity away from him. Apparently, they thought it would come in handy to quell the growing civil unrest going on about town, particularly since its rate of fire was rumored to be 200 rounds per minute.

In police custody, Dickinson’s steam-powered menace was temporarily housed at the foundry of wealthy Ross Winans. Winans was an active, vocal supporter of states’ rights and suddenly the Dickinson centrifugal weapon became attributed to him. Meanwhile, Winans was also labeled as an agent of the Confederacy. Partisan politics has always been a rough game, and in those days, it could get you hanged, depending on where you were standing.

As a result, the Baltimore police returned it to Dickinson, the rightful owner. Shortly afterwards, Dickinson tried to take his brainchild to Harper’s Ferry, ostensibly to sell to rebel forces. He was intercepted along the way by Union troops. The Federals took his gun away, again, and this time for good.

Back in Baltimore, Ross Winans, continuing to struggle with bad publicity and was jailed for a few days on suspicion of his involvement in selling the untried “super weapon” to the Confederacy. He was released on his promise to never take up arms against Abe Lincoln and the government in Washington. The Dickinson invention went back to Massachusetts without ever firing a shot in anger. The Civil War ended with no centrifugal-fire casualties that anyone is sure of, but when the concept was first discussed, several folks were nearly scared to death.

A Bunch of Hot Air?

The Civil War era media was certainly impressed by the centrifugal gun concept. The following is an excerpt of the text of a Harper’s Weekly article from May 25, 1861, describing the Winans “Steam Gun” as captured by a Colonel Jones on the way to Harper’s Ferry:

This most efficient engine stands without a parallel commanding wonder and admiration at the simplicity of its construction and the destructiveness of its effects; and is eventually destined to inaugurate a new era in the science of war.

Rendered ball proof, and protected by an iron cone, and mounted on a four-wheeled carriage, it can be readily moved from place to place or kept on the march with an army. It can be constructed to discharge missiles of any capacity from an ounce ball to a twenty-four-pound shot, with a force and range equal to the most approved gunpowder projectiles and can discharge from one hundred to five hundred balls per minute.

For city or harbor defense it would prove more efficient than the largest battery. For use on the battlefield (the musket caliber engine) would mow down opposing troops as the scythe mows standing grain; and in sea-fights, mounted on low-decked steamers, it would be capable of sinking any ordinary war-vessel. “In addition to the advantages of power, continuous action, and velocity of discharge, may be added economy, in cost of construction, in space, labor, and transportation, all of which would be small in comparison to the cost and working of batteries of cannon, and the equipment and management of a proportionate force of infantry.” The possession of this engine — ball-proof, and cased in iron — will give the powers using it such decided advantages as will strike terror to the hearts of opposing forces, and render its possessors impregnable to armies provided with ordinary offensive weapons.

To the Trenches

Turn the clock forward to 1918, and the last year of World War I. America had joined the Allies against Germany and the Central Powers less than a year before, and American inventors saw the opportunity to supply Uncle Sam with powerful new weapons. Some of them revisited the centrifugal gun concept. One of these men was Levi Lombard.

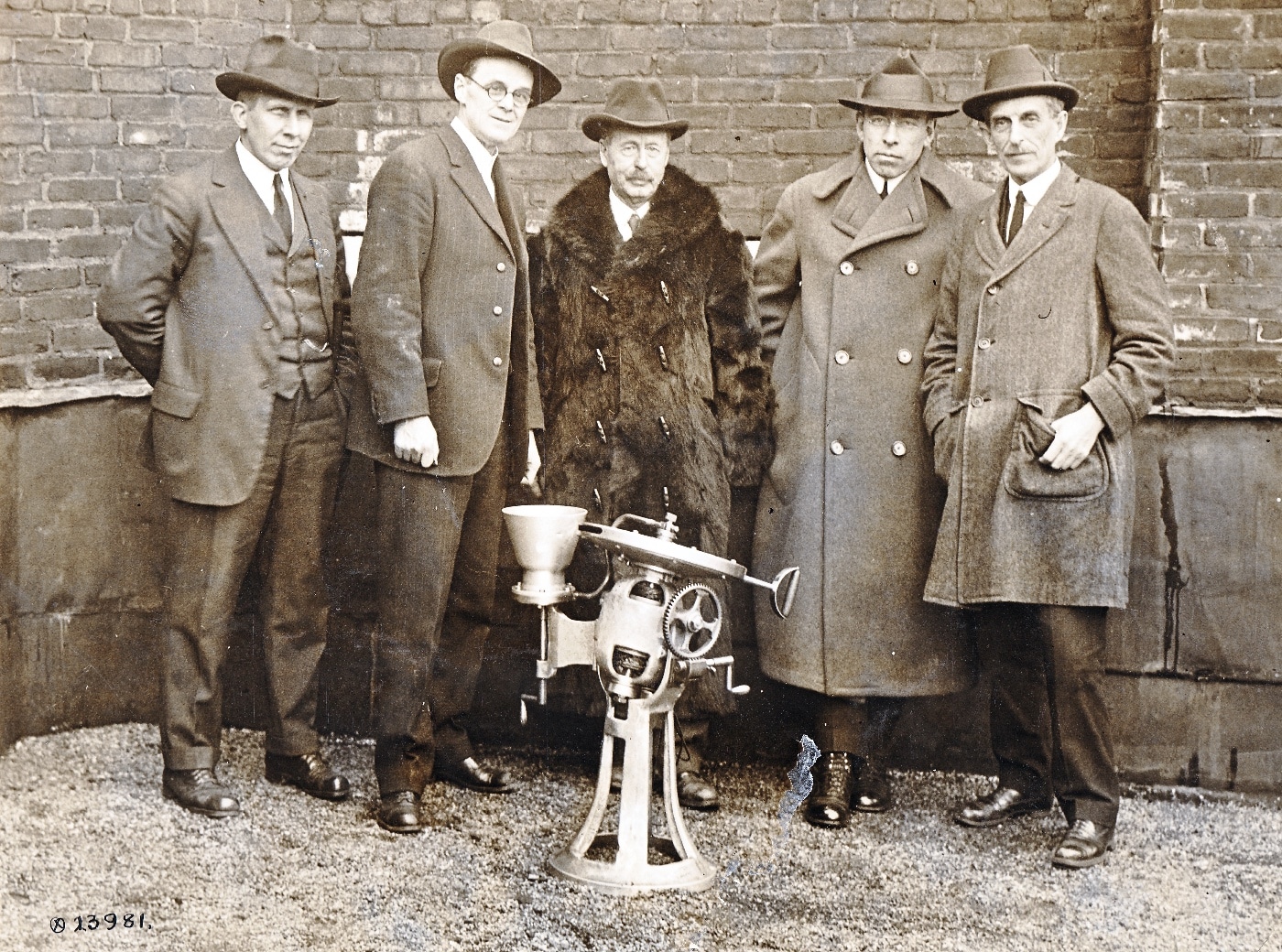

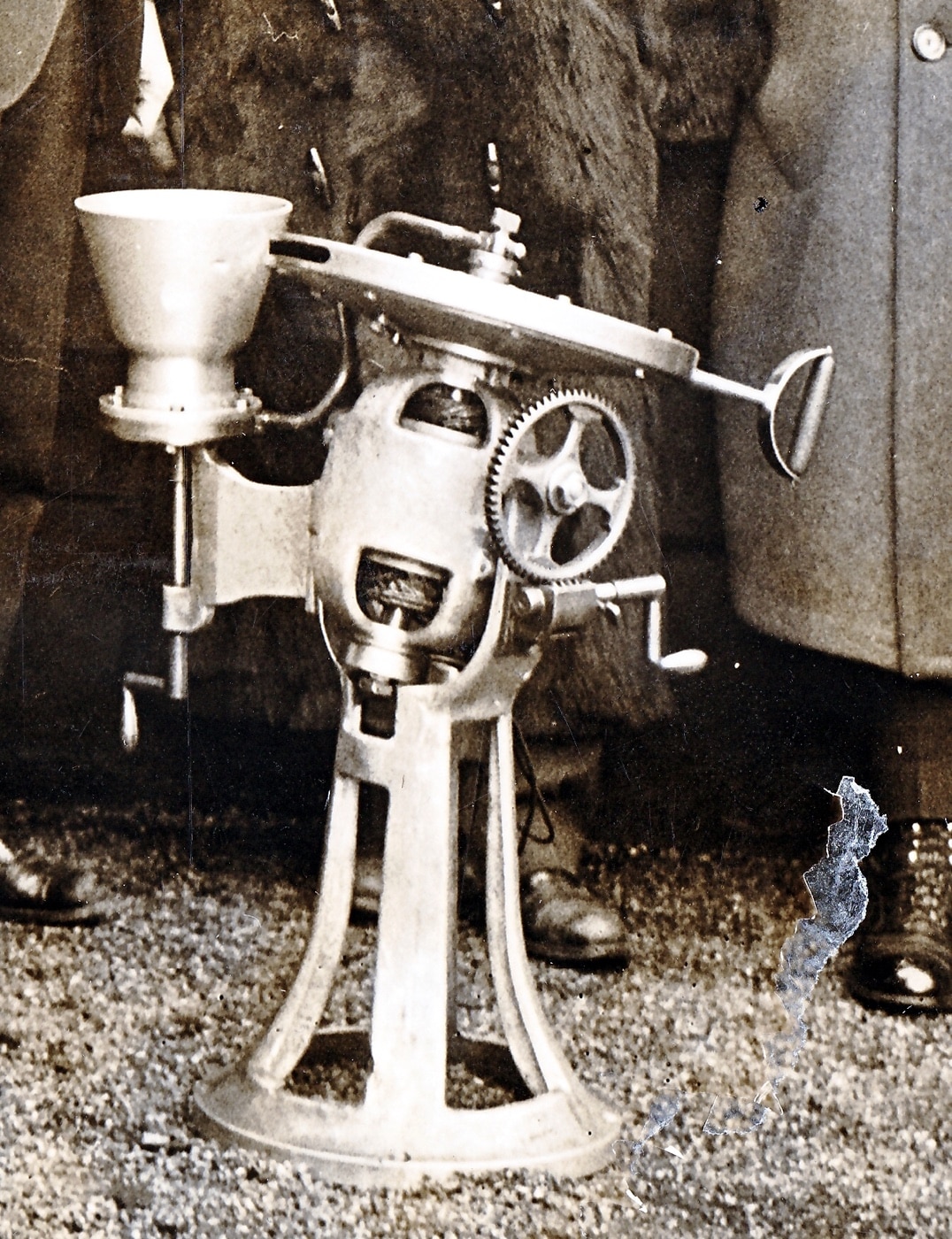

I found a photo of Mr. Lombard and his associates in Boston, dated March 1918. The official caption describes the device in the foreground as a “centrifuge gun”. It also mentioned that the weapon’s rate of fire was 33,000 rounds per minute! Despite the fact that the “Lombard gun” had no barrel, its ability to fire at more than 500 rounds per second certainly attracted the US Army’s attention, at least for the moment. That’s when the difficult questions about the concept’s practicality started to arise.

There is some evidence that several centrifuge weapon designs were either tested or reviewed by branches of the U.S. Government during World War I, including the U.S. Bureau of Standards. Several patents were issued, continuing into the early 1920s. These ranged from a “silent machine gun” powered by a large electric motor to apparently a much noisier variation powered by an aircraft engine. Comments from U.S. Ordnance reviewers remained consistent though, beginning with assessments like “woefully inaccurate” and “beyond resolution”, and concluding with “rejected”.

Despite breath-taking stats for rate of fire, the centrifugal gun systems were unlikely to hit anything, ever, and if they did strike a human target the bullet might not even break the skin. Additionally, the battlefields of the era were devoid of electrical outlets, which proved a grave inconvenience to the designs that used an electric motor. The centrifuge gun seems most potent in the clean room confines of a laboratory, and not so much in the harsh environment of the killing fields or even the proving grounds.

Conclusion

Even now, the concept still lingers. During 2005, a 21st Century centrifugal gun was announced, titled the “DREAD Weapon System”. Many impressive claims have been made in DREAD’s marketing materials, from a rate of fire reaching 120,000 rounds per minute, to the silent, recoilless, flash-less, jam-proof, self-cleaning, low-heat signature operational characteristics of the weapon. However, there are no reports on accuracy or striking power, but I’m sure those minor details are being addressed.

As for you dedicated rifle marksmen or deadeye hand-gunners, it is probably worthwhile to hold on to your musket or six-gun (or even slingshot) until they work out all the kinks on the old newfangled centrifugal gun.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

![Best Micro Compact 9mm Pistols [Field Tested] Best Micro Compact 9mm Pistols [Field Tested]](https://i2.wp.com/gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/EDC-X9-2-review-target.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)