The preparations for the invasion of Normandy are almost beyond comprehension. The single greatest military operation in the history of mankind required the complete attention of the Allies’ combined land, sea, and air forces. And yet, after the beachhead in Normandy was won, a more fearsome battle waited just beyond the sands.

The Norman countryside provided near-perfect territory for the defenders, and as more and more German units arrived in the area, the hard-won beachhead turned quickly into a deadly bottleneck.

Missing the Forest for the Trees

While you can’t anticipate everything, there was a critical component to the battle of Normandy that the Allied planners had overlooked: the hedgerows of the “Bocage country”. These man-made and natural obstacles proved to be some of the most effective defensive positions of the entire war. And this was particularly so in the American sector.

The hedgerow country began about 10 miles inland from the invasion beaches, and this peculiar feature dominated the landscape all the way to the western edge of the Cotentin Peninsula. Norman hedgerows were a centuries-old practice used by the farmers in the region to divide their fields, pastures and orchards. Each field was small, most less than 500 yards, with some less than 200 yards in size.

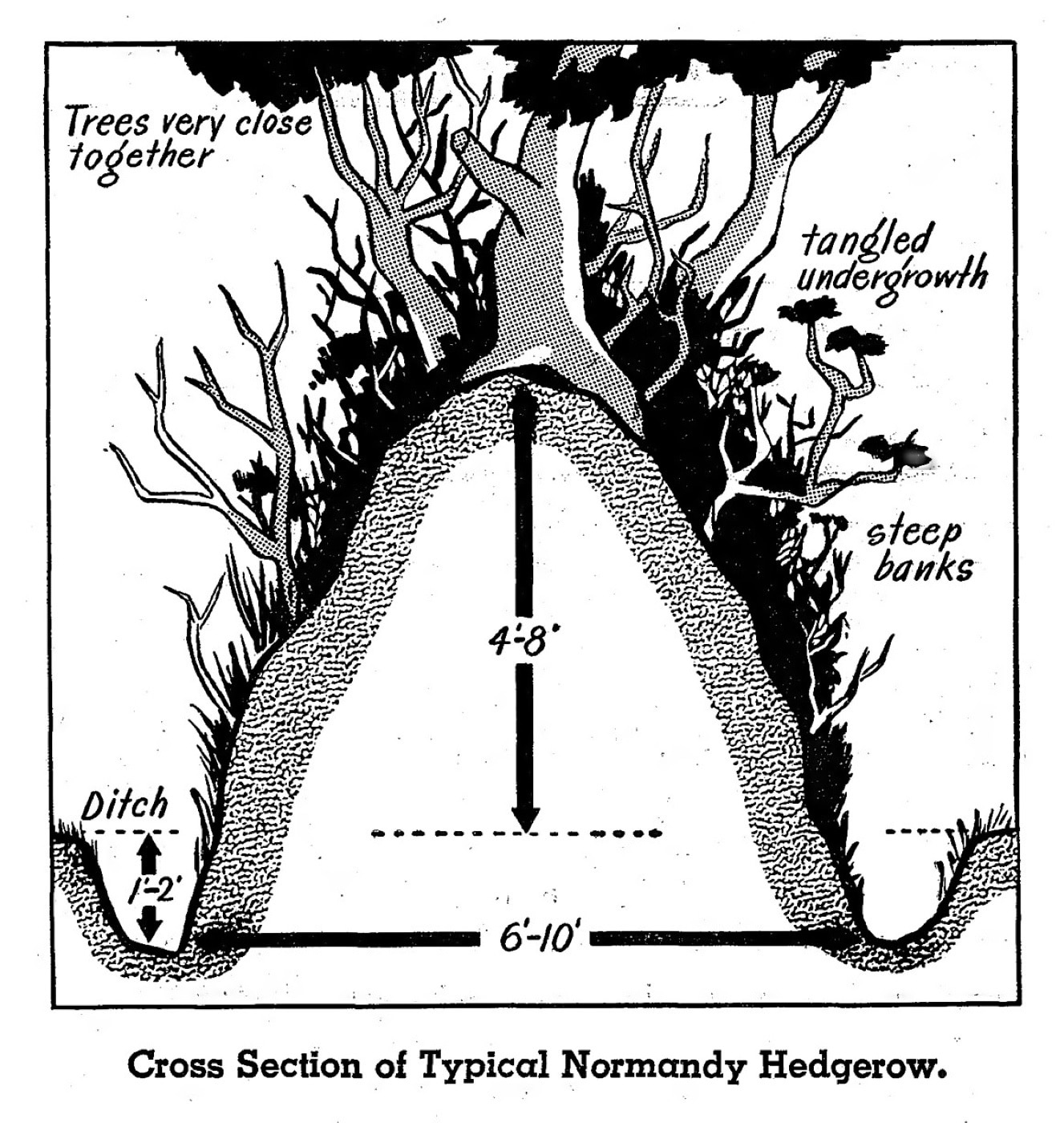

The typical hedgerow in Normandy was a combination of a sturdy embankment (up to four feet thick), that could range up to 15 feet high. Atop the embankment grew the hedge, often featuring a tangle of vines, small trees and shrubs. Ultimately, the hedgerows created a battlefield of walled compounds — each with its own opening, but with very few connected to each other. Some were accessible by road, but the roads in Normandy were normally quite narrow. Many hedges were accessible by tiny, rutted wagon trails.

Almost everything about the Bocage country favored the German defenders. To make matters worse for American troops, little or no training had been provided to deal with the hedgerows, nor was there specialized equipment ready to work in the Bocage. General Omar Bradley observed the hedgerow country as early as June 8th, and immediately pronounced it: “The damndest country I’ve seen.” The stage was set for a terrible fight to break out of Normandy.

Stubborn Defenses

Hitler demanded that his troops mount a “stubborn defense” in Normandy, and the terrain features gave the German forces every opportunity to do it. Among the hedgerows, much of the American force’s ability for fire-and-movement would be negated. Meanwhile, a small number of German troops could pin down an American advance, and Wehrmacht commanders seized every opportunity to inflict heavy casualties and make their traditional counterattacks. Normal tactical maneuvers were not possible in the Bocage, and with American armored units often bottled up, or simply road-bound, the Normandy campaign would frequently be a ground-pounding infantry fight.

German defenses turned each farm field into a strongpoint protected by direct and indirect fire. Machine guns like the MG 42 and MG 34 were emplaced in earthen embankments dug out of the hedgerows — set up on tripods for maximum accuracy. Light machine gun teams were ready to move to attack the American troops from the flanks.

Once an American assault was stalled or pinned, pre-sighted indirect fire was called in from available artillery and mortars. The German 8cm “Granatwerfer 34” was highly effective, firing a nearly 8-pound shell out to about 1,300 yards. Studies revealed that as much as 75 percent of all American casualties during the Normandy campaign were caused by mortar fire.

German defensive positions were linked by field telephone, providing the ability to coordinate the defense of an entire sector. Mines and booby traps were common, and German trip-wire explosives became a notable feature of their defenses in Normandy. In the tight confines of the Norman roads and trails, the German Panzerschreck rocket launcher and Panzerfaust anti-tank grenade launcher were effective in ambush against American tanks.

Road junctures and the corners of key hedgerow defenses were covered by German anti-tank guns, both the efficient 75mm Pak 40, and the renowned 88mm — the tankers boogie man of WWII. Some German tanks and self-propelled guns added their weapons to defensive positions, particularly when American tanks were expected to be nearby.

Sniper!

Snipers were a critical component to the German defenses in Normandy. The concern about snipers often made inexperienced units hesitant, often with dire consequences.

The following comments about German snipers in the Normandy campaign come from a U.S. Army wartime series titled “Combat Lessons”:

The German soldiers had been given orders to stay in their positions and, unless you rooted them out, they would stay, even though your attack had passed by or over them. Some of their snipers stayed hidden for 2 to 5 days after a position had been taken and then ‘popped up’ suddenly with a rifle or AT grenade launcher to take the shot for which they had been waiting.

We found firecrackers with a slow burning fuse left by snipers and AT gun crews in their old positions when they moved. These exploded at irregular intervals, giving the impression that the position was still occupied by enemy forces.

High losses among tank commanders have been caused by German snipers. Keep buttoned up, as the German rifleman concentrates on such profitable targets. This is especially true in villages. After an action the turret of the commander’s tank is usually well marked with rifle bullets.

One infantry regimental commander provided a detailed description of the German defensive organization:

We found that the enemy employed very few troops with an extremely large number of automatic weapons. All personnel and automatic weapons were well dug in along the hedgerows in excellent firing positions. In most cases the approaches to these positions were covered by mortar fire. Additional fire support was provided by artillery field pieces of 75mm, 88mm, and 240mm caliber firing both time and percussion fire. Numerous snipers located in trees, houses, and towers were used.

On several occasions the Germans have allowed small patrols of ours to enter villages and wander around unmolested, but when stronger forces were sent forward to occupy the village, they would encounter strong resistance. The Germans will permit a patrol to gather erroneous information in order to ambush the follow-up troops acting on the patrol’s false report.

With all openings to the hedgerows covered, American rifle companies tried to chop their way through the dense growth atop the hedges, only to find German MGs in their face and grazing their flanks. Pinned down in a kill zone, many green units froze and were targeted by snipers as mortar fire fell among them. The doctrine of fire-and-movement was too often forgotten, with dire consequences.

Further comments from “Combat Lessons” describe a lack of intensity in American infantry attacks:

Interrogation of German prisoners during the hedgerow battles revealed that even the Germans detected a lack of aggressive drive among the American infantry units. Prisoners stated that the American infantry moved too cautiously and consequently failed to take weakly held positions. They were surprised that artillery barrages were not followed up by determined infantry assaults. An experienced corporal in the German 275th Infantry Division summed up German attitudes: “Americans use infantry cautiously. If they used it the way Russians do, they would be in Paris now.

Inexperienced troops tended to stop moving under fire, seeking the nearest available cover or even freezing in the open. A platoon leader in the 9th Infantry Division described the reaction of new men under fire:

One of the fatal mistakes made by infantry replacements is to hit the ground and freeze when fired upon. Once I ordered a squad to advance from one hedgerow to another. During the movement one man was shot by a sniper firing one round. The entire squad hit the ground and they were picked off, one by one, by the same sniper.

Another problem encountered with green troops was their inability to open fire on the enemy.

Reinforcements have no idea of when to open fire. Reconnaissance by fire is unknown to them. In moving through wooded areas, green men would observe the enemy within 150 yards but would not fire a shot until the platoon leader did. They thought they might waste ammunition. They should know when they reach us that it is better to expend ammunition on positions that are not occupied than fail to cover it and learn later that it was occupied.

My father served with the 8th Infantry Division, and he was a veteran of the hedgerow fighting. He described to me that the men had to “unlearn” certain concepts that were impressed upon them in training. The fighting in Normandy quickly reshaped their tactics, particularly the notion that the G.I.s must see a target before they could shoot at it. He commented: “After a week in Normandy, we shot at anything that looked or sounded suspicious.”

Fire and Movement

Classic infantry principles still worked, but flexible, innovative methods were needed to fit the tactical situation. An Infantry regimental commander in Normandy commented in Combat Lessons:

Fire-and-movement is still the only sound way to advance your infantry in daylight fighting. Build up a good strong base of fire with automatic rifles and light machine guns. The heavy machine guns are much more effective, but it is difficult to keep them with the advance. Use your 60-mm mortars to deepen and thicken your covering fire. When you are all set, cut loose with all you’ve got to keep Jerry’s head down while the riflemen close in from the flanks and clean him out.

Dozers, Rhinos, and Plows

The battles in the Bocage saw plenty of courage among U.S. troops, along with a healthy dose of American ingenuity. By the end of June 1944, American commanders were frustrated by their lack of progress as the Norman hedgerows presented the immovable object in the German defenses.

The first solution came in the form of the M4 Sherman tank fitted with a bulldozer blade. The Sherman dozer kept the tank’s turret-mounted 75mm gun and coaxial .30 caliber machine gun, while adding the earth-moving ability of a Caterpillar D8 tractor. The dozer tanks could carve out a clean opening in the hedgerow for other tanks and troops to move through. General Eisenhower called the tank-dozers a “Godsend”. Unfortunately, there were far too few of them available in Normandy, and other means were needed quickly.

U.S. combat engineers used a pair of 25, and later 50-pound charges, to blast a hole in the hedges that tanks and infantry could pass through. Other innovations came from American tank units: First Lieutenant Charles B. Green of the 747th Tank Battalion used salvaged railroad ties to create a massive pair of prongs fitted to the bow of a Sherman tank — offering the ability to ram through most hedgerows. Meanwhile, Sergeant Curtis G. Culin used iron girders salvaged from German beach landing obstacles to create a hedgerow cutter for American tanks. A series of teeth or horns was welded to the vehicle’s bow, providing the ability to cut through the hedges. Tanks fitted with the Culin device were often known as “Rhinos”. By late July, more than 60% of all US 1st Army tanks were fitted with the hedge-cutters.

Major-General Charles Gerhardt, commanding the 29th Infantry Division, commented on the use of the hedge-cutters in this report from August 5, 1944:

The 2nd Battalion, 115th Infantry and Company “A”, 747th Medium Tank Battalion attacked St. Andre de L’Epine using our infantry tank tactics as outlined on a chart which I previously furnished you. This attack was very successful. There was a 3,000-yard advance with a 90-degree change in direction to the right without losing a tank. The infantry would clean out the bazookas and faustpatrones from the hedgerows before they got a shot at a tank. The new lesson is that tanks should operate in pairs, not abreast but In column, with one field separating them, for the reason that when one runs out of gas or ammunition the other can take over. In other words, the tanks leapfrog each other. Originally, we used two 50-pound charges set off by the accompanying engineers to blast holes in the hedgerows for the passage of tanks. In an effort to reduce the size of the charge tanks were equipped with two prongs for punching holes in the hedgerow in which 15 pounds charges were placed and tamped. The tanks soon discovered that, just like elephants rolling teak logs with their tusks, the prongs were lifting out the hedgerows and no charges were necessary. Two improvements on these prongs have been made in the First Army. One is called a rhino and consists of a series of sawed-off angle irons which act as huge teeth welded to the front of the tank. The other is a bumper made from captured railroad irons.

Meanwhile, tank and infantry team tactics were taught and rehearsed just beyond the Normandy beachhead. More and more replacements learned enough to make them effective in the Bocage. Tankers learned to stay back from the German-occupied hedgerows as best they could, to avoid close assaults with satchel charges or Panzerfausts. Tank-infantry communication overcame their differences in radio frequencies by using a telephone handset mounted on the rear deck and plugged directly into the tank crew’s intercom. As the hedgerows were smashed open, American tanks blasted German MG positions at point-blank range while the advancing infantry suppressed German anti-tank teams. The tank-and-infantry assault became a brutal exercise in blocking and tackling basics — demolishing one hedgerow position after another until the road to Paris was open.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here