We discuss a truly American rifle story that spans over 200 years and five generations.

If you’re a firearms enthusiast, then this story is for you. The tale spans more than 200 years and five generations. And unlike histories that examine most rifles, the rifles described here are, perhaps, out of your reach. To quote the great gun writer Townsend Whelen, “The placing of the bullet is everything.” Here you’ll see what an early gunmaker did to help shooters “place the bullet,” and how his descendant continues the tradition.

The story starts in Virginia in 1802 when Joseph Carper, the son of German immigrants, was born. In 1848, he acquired a large tract of land in what is now West Virginia. Joseph traded one rifle for all you could see from a high point that overlooked the New River. It’s hard to say exactly how much land this involved and interesting to argue how a century-old transaction of this nature would hold up in court.

But, more important, is the fact that Joseph built the rifle he traded for this land. Legend has it was a stunning piece, decorated with silver and muscle shell from the New River. On that land, Joseph built a gun shop and a home, and today, some of the property is part of what’s now known as the New River Gorge National Park. The whereabouts of the rifle involved in this trade is unknown.

Early Carper Rifles

Carper rifles were frequently banned from many pioneer shooting matches, and a Carper rifle won top prize at Virginia’s State Fair back when a state fair was genuinely important. The excellence of these rifles didn’t go unnoticed by the government. During the Civil War, or the “War of Northern Aggression” as it’s often referred to in the South, Yankee Cavalry descended upon the Carper home. Carper’s brothers were away serving in a Confederate Sharpshooter Battalion, leaving only Joseph, his wife and a small boy on the farm. The northerners burned Carper’s gun shop to the ground.

A stroke took Joseph’s life in 1880 while he was working in his shop. His son, Samuel, finished the rifle Joseph was working on and continued to make rifles until 1927. This was well into the age of the smokeless cartridge—the 3,000-fps .250 Savage and the .30-06.

Why would a gunmaker continue to make rifles far eclipsed in technology for that many years? It’s simple: demand. Carper rifles were marvelously accurate because of the unique procedure used to rifle the barrels by hand.

Barrels, Not Booze

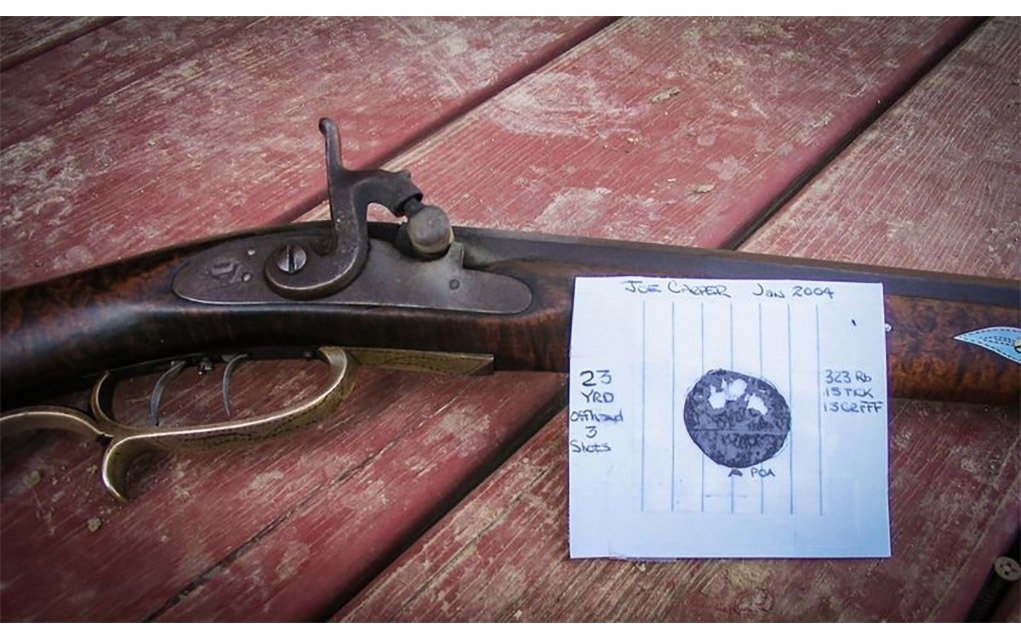

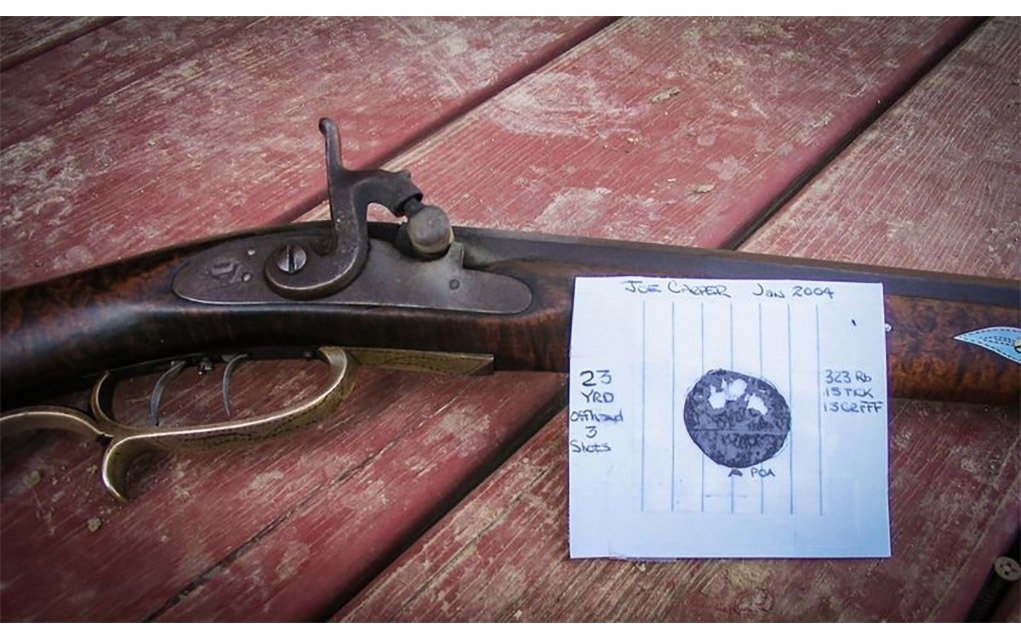

Today, there are only a handful of Carper rifles in existence. John Walker, a fifth-generation descendant of Joseph, has two of them and he knows where most of the others are. But more importantly, Walker builds his own muzzleloaders the same way his ancestors did.

Walker grew up in the shadow of his grandfather, an accomplished outdoorsman, and his father, who was a talented woodworker. These influences, in conjunction with the Carper legacy, steered Walker to develop an interest in hunting, firearms and rifle building. His uncle still had some of the gunmaking tools used by the Carpers, and after intense study and dubious research, Walker put the famous Carper barrel-rifling machine to work.

The process by which these barrels are rifled would make modern barrel manufacturers eye them like a rabid skunk. Nonetheless, the fact remains that Walker managed to duplicate the process that made the Carper rifle such a tack-driving frontier tool worth vast expanses of terra firma and the intervention of the Union Army.

The rifling machine utilizes a wooden gear about 6 inches in diameter and about 4 feet long. This spiral-fluted fence post corresponds to the rifling grooves it’ll help cut into the barrel. To one end, a handle is attached, and a chuck is fastened to the other. This allows the gear to be pulled through a guide that keeps the mechanism spiraling and straight.

A steel rod is attached to the chuck, and on its end is a short length of hickory that’s split, with steel cutting blades pinned in place. A barrel is clamped to the base in front of the chuck, and the rod is inserted through the barrel, leaving the cutter protruding from the end of the barrel. This allows the cutter to be pulled through the barrel and then pushed back, cutting one groove at a time.

As needed, shims are inserted into the split in the hickory to deepen the groove being cut. The entire process is an event that’s invisible to the builder and requires a talented touch. Walker says it takes about 8 hours to rifle a barrel, and he knows it’s done “when it feels right.”

Patching with Pride

A top-quality muzzleloading rifle barrel of modern manufacture can be had for a couple hundred bucks. So why, you might ask—other than nostalgia—would Walker make his own using this archaic method? Walker used to compete regularly with his rifles, and the Alvin C. York Memorial Shoot held in Pall Mall, Tennessee, was one of his favorite matches; it could be called the Muzzleloading Olympics. Hundreds of contestants flock there every year to prove their muzzleloaders shoot better than any on the planet.

Most of these guns are heavy and designed to be shot over a log—they’re called “chunk guns;” some weigh 20 pounds or more. Open sights and round balls are all that’s permitted. Walker had tried barrels from Green Mountain, Douglas and Getz, but with a patched round ball he found they couldn’t deliver the precision of his original Carper rifles.

The secret lay in the geometry of the rifling and the slow, tedious process, that in effect, laps the bore as it cuts the groves. With one of his hunting-weight rifles, wearing a barrel of his making, Walker attended this shoot in 1998 and placed in the top 40, or “in the beef,” as it’s called. No trophies are awarded at this shoot; various portions of beef are distributed to the top 40 shooters.

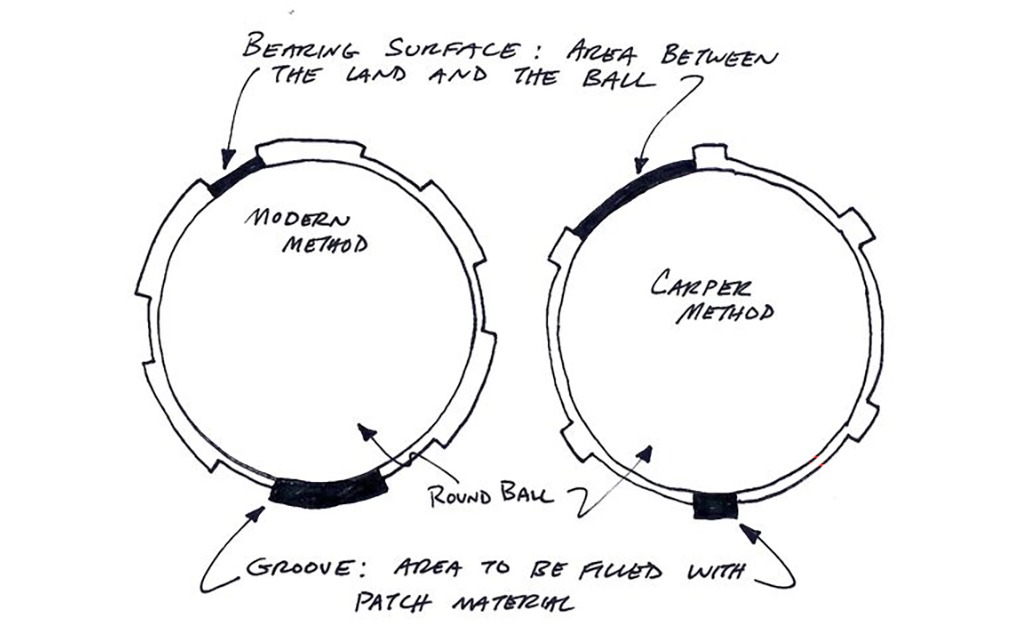

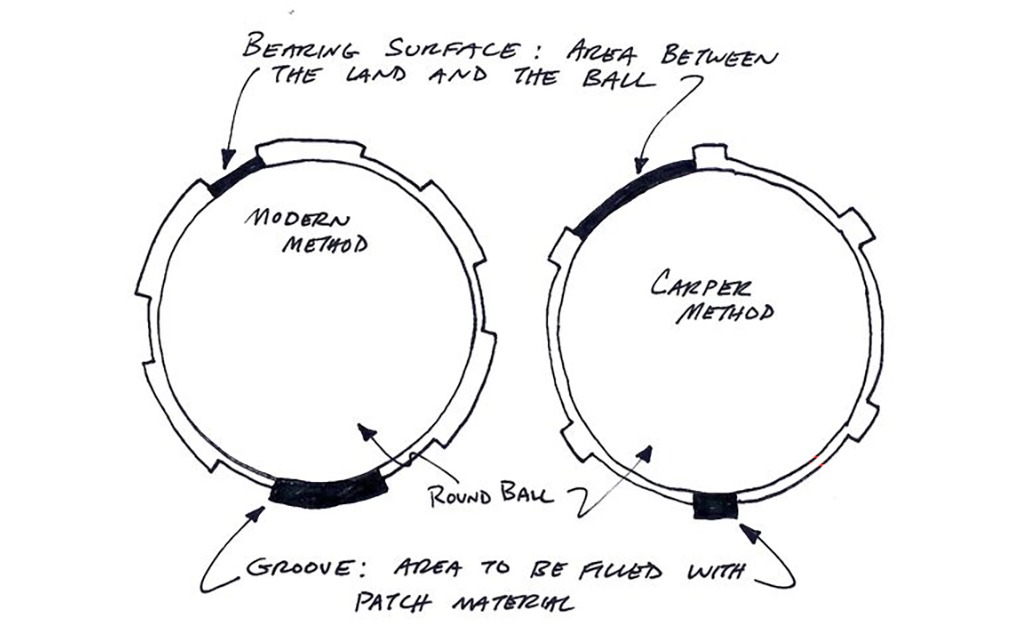

To understand why the Carper technique is so effective at shooting patched round balls, you first must understand what’s wrong with the design of modern muzzleloading barrels. Modern muzzleloading barrels very much resemble barrels for jacketed or cast bullets in modern cartridge guns. They consist of wide grooves and narrow lands. This works perfectly for jacketed bullets that are sized to the “groove to groove” dimension of the barrel. The wide groove offers a large bearing surface, and the narrow lands get the bullet spinning with minimal distortion. A patched round ball needs the same spin, but this type of barrel cannot effectively provide it.

The bearing surface for a patched round ball isn’t found in the groove but in the area between the land and the ball, which is separated by the patch. The weave of the patch grabs the ball, as it’s forced down the barrel during bullet exit, applying pressure to the bearing surface. A ball doesn’t deform down into the entire depth of the groove like a conical bullet. A wide groove needs too much patch, and the ball cuts the patch at the outside corners of the lands. This need for patch means balls end up being well under bore size to allow for a thick patch in hopes of preventing the “pinch cut” at the corner of the land, and the “burn-through” the wide groove will allow.

The Carper method is the opposite. To start, grooves are narrow, allowing only a smidgen of patch to enter the groove when the ball is loaded … just enough to relay the spin of the rifling to the ball. A narrow groove doesn’t allow as much burn through and doesn’t require such a thick patch to fill the gap. The wide lands mean the bearing surface is greater and more of the patch’s weave is impressed into the ball. This all means that a ball closer to the size of the land-to-land diameter or bearing surface can be used.

So, just as with modern bullets in modern barrels, what you have is maximum bearing and minimal distortion—not with the bullet, but with the patch! The patch is the key and that’s what a round-ball rifle must be made to harmonize with. Of course, the smoothness of the bore helps maintain patch integrity during loading and shooting. Walker rifles have won more West Virginia State Metallic Muzzleloading matches than any other. I used mine to win that match, and Walker has won it several times.

Up until about 2015, Walker just built his rifles for family and friends. He’s the only rifle maker I know who picked his customer. But that same year Walker stopped making guns, sold his farm and moved to Kodiak, Alaska, to run the Baptist Mission. To survive, the organization needed an organizer and someone with the hillbilly ingenuity like Walker has in spades. Since then, Walker saved the mission and turned it into an educational institution for youths, where they learn how to ride horses, shoot guns, make knives, grow food and, most importantly, tell the truth.

With the gun-building virus still inside him, Walker recently had his son ship his barrel rifling tools to Kodiak. Now, with the help of his daughter, Jenna, who by the way is a very talented knifemaker and engraver, he’s building rifles again. They’re exquisite works of historic art, conjured into existence with hours and hours of handwork.

They’re not gaudy, and they’re not fancy. Walker will tell you straight-up, “They’re nothing like you would find in the hands of a Pennsylvania pimp.” The rifles Walker builds now emulate the working, mountain-style rifles made in East Tennessee during the early to late 1800s. But everyone is hand-fitted to perfection and has a barrel that’s been hand-rifled using the original Carper rifling machine.

If you enjoy a challenge, call Walker up and try to persuade him to build you one of his rifles. You’ll have to convince him you deserve it, and that you’ll shoot it. Walker has no interest in building mantle pieces; he wants his rifles to be shot and hunted with. You’ll also have to send him a check for $5,000. Good luck! If you’re fortunate enough to become the recipient of a Walker rifle—by gift, trade, fortune or money—it’ll carry with it not only the legacy of a family of talented gunmakers, but also a historical link to the past.

Oh, and you can be sure it’ll “place the bullet” better than you can.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Historical Firearms:

Read the full article here