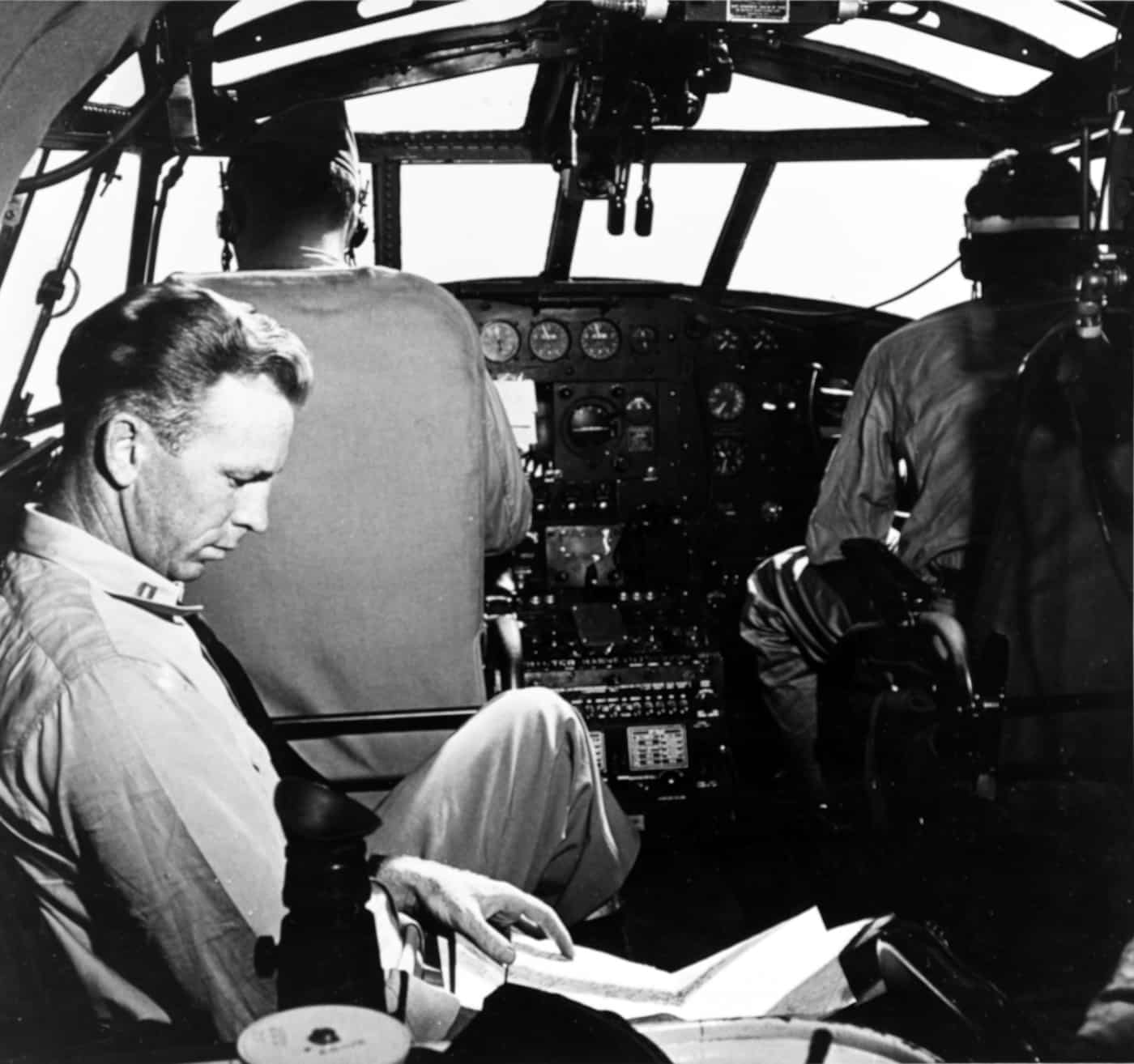

Nervously, Herbert “Johnny” Johnson scanned the night sky from a cramped position in his Martin PBM Mariner. The flight over the Sea of Japan was relatively short, but they were flying alone through a war zone, and the enemy had proven to be tougher and better equipped than many of them anticipated.

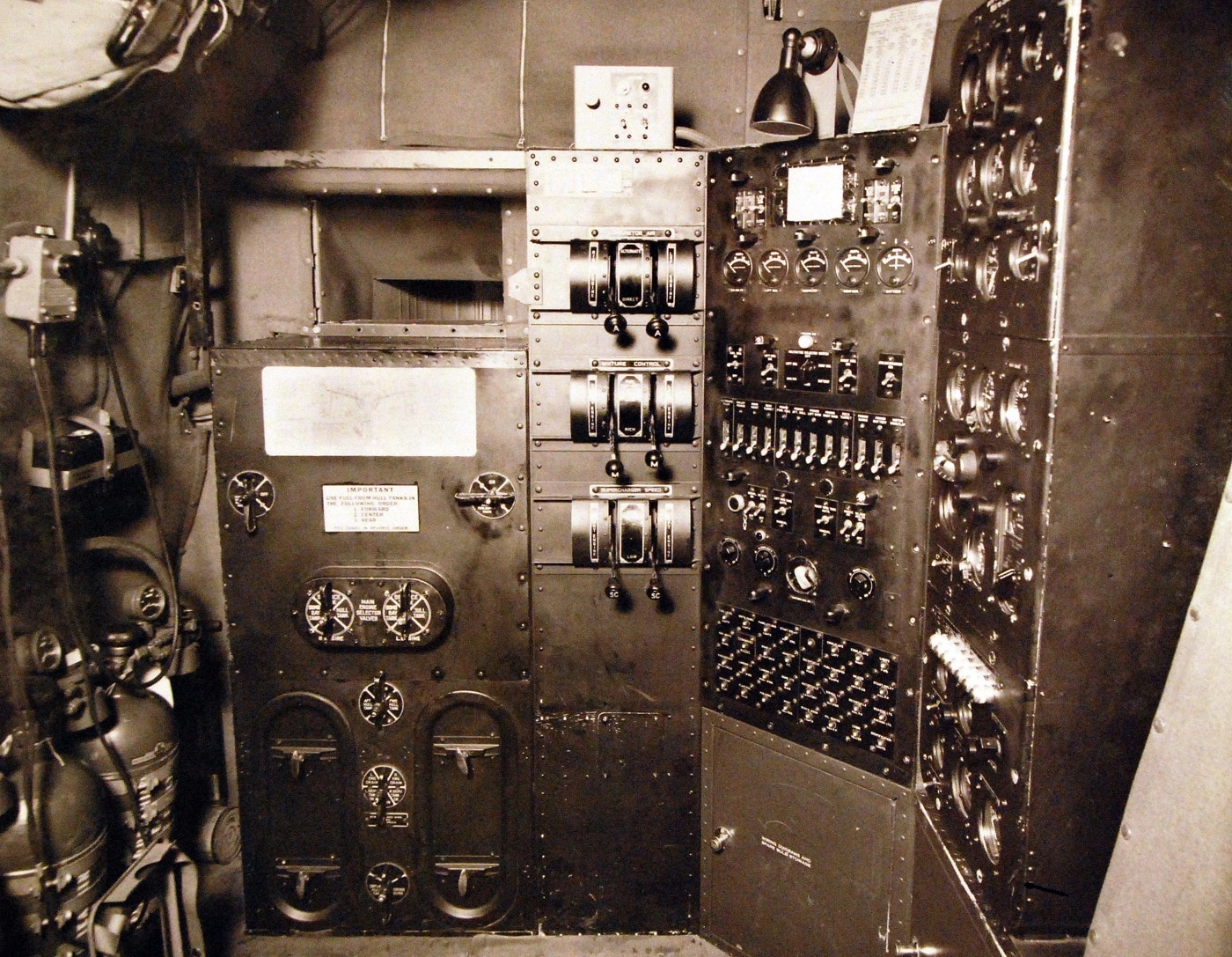

Johnny Johnson was the plane’s flight engineer, the same role he’d had only five years previous when on anti-submarine patrols in World War II. Then he was watching for Japanese fighters. This time, Johnson was looking for North Korean Yak-9U and Ilyushin Il-10 fighters instead of Zeros and Oscars.

Of course, there wasn’t much he could do even if he did spot an enemy aircraft. All eight of the M2 .50-cal machine guns, and some of the sailors who normally manned them, had been pulled out of the plane to allow more supplies to be packed in.

American and South Korean troops had been pushed back to an area they were calling the “Puson Perimeter” and were holding on for dear life. They needed every ration, bullet and bandage packed into the plane. Consequently, the plane’s guns were deemed superfluous and removed in favor of some bit of kit a soldier or Marine needed on the front line.

The only defensive firepower on the entire plane was the pilot’s M1911A1 riding in a leather shoulder holster. None of them had any illusions where that left them. If they were jumped by a North Korean pilot, they would be lucky to survive. At least the large PBM was a “flying boat” that could safely put down on the water — assuming they lasted that long.

Johnson checked his watch. “We should be getting pretty close to Puson,” he thought. He settled back into his position and kept an eye on all the gauges.

Shortly, the plane began to make a turn as the pilot lined up for a landing. A slight amount of comfort crept in as Johnson thought they had made another successful run. But now, the hard work started. As the flight engineer, he had to get the plane readied for a return flight to Japan so they could do it all over again. Listening for commands from the pilot, Johnson got to work.

The Martin PBM Mariner

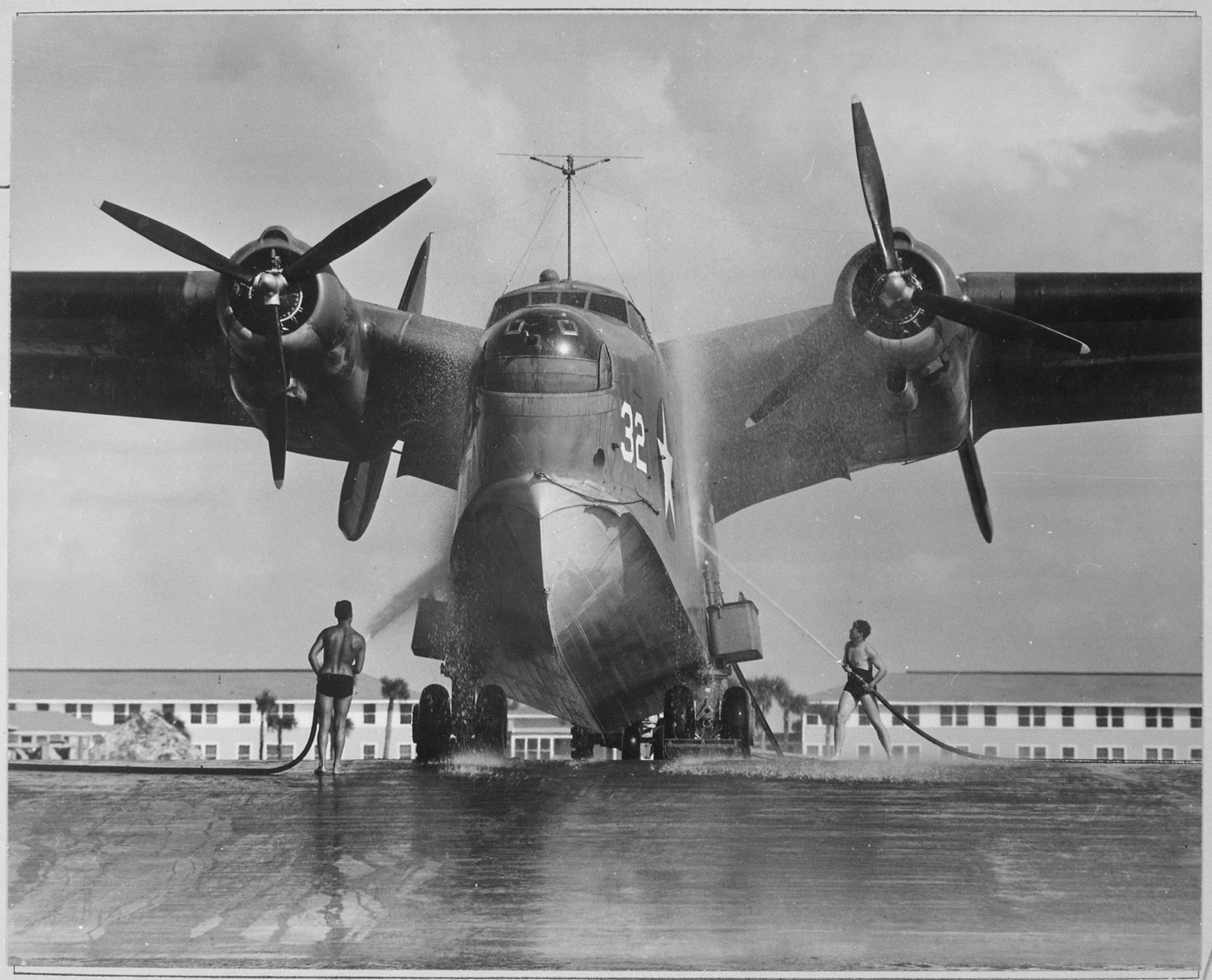

The Martin PBM Mariner was a twin-engine flying boat developed in the late 1930s. Originally designed by the Martin company to compete against the Consolidated PBY Catalina for a Navy contract, the planes ultimately were ordered as a replacement for the PBY.

Employed by the U.S. Navy as a patrol bomber in World War II and the Korean War, these planes were taller, longer and had a broader wingspan than the B-17 Flying Fortress. It’s hard to appreciate how much bigger the PBM was until you saw one side-by-side with a B-17.

Like the B-17 heavy bomber, the PBM was festooned with .50-caliber machine guns and could carry a formidable payload over long distances. In fact, with a similar payload, the PBM had longer legs than the Fortress. And if needed, the PBM could fly for hours on a single engine.

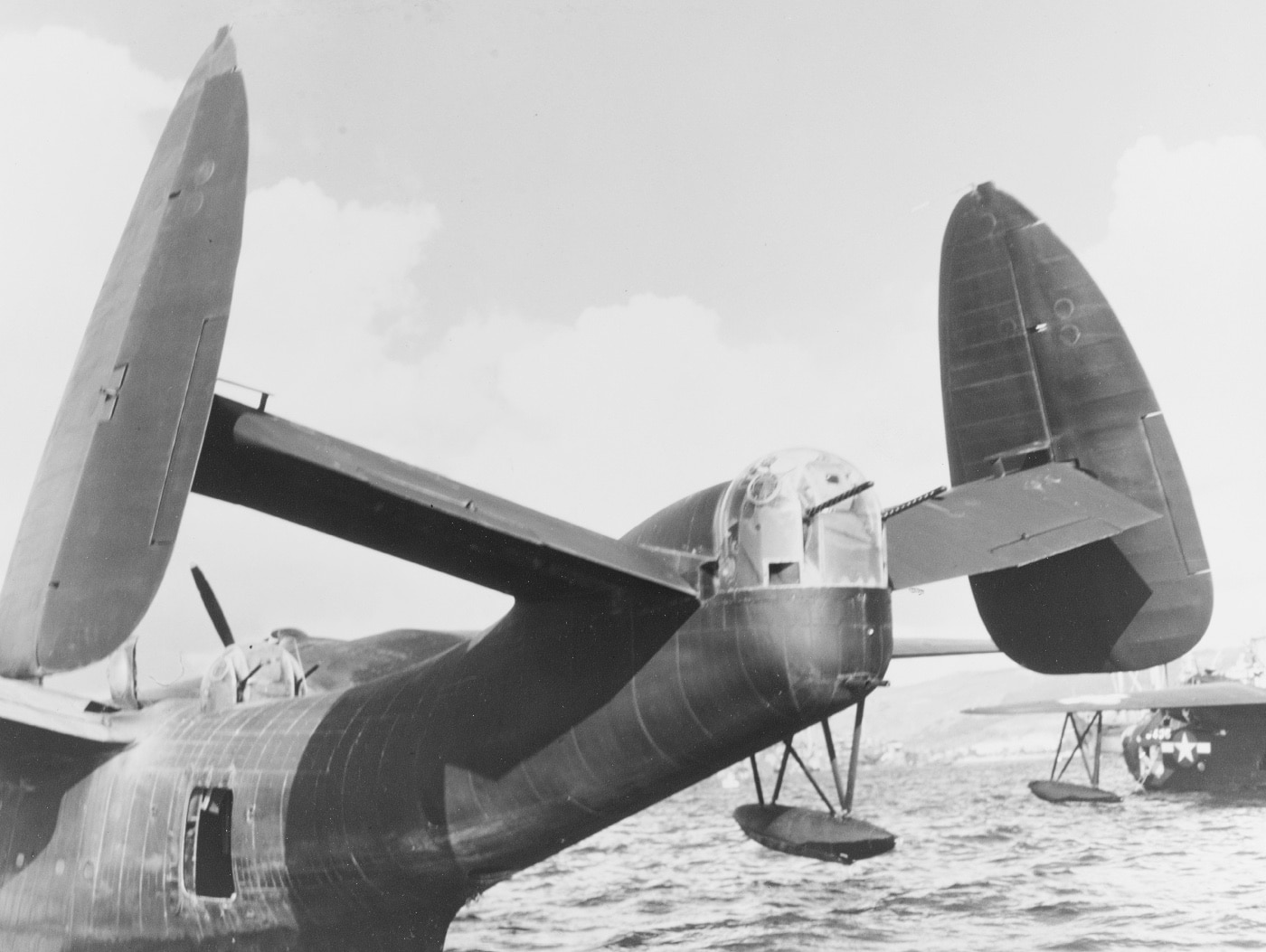

Unlike the B-17, the Martin PBM was designed to take off and land on the water.

What Is a Flying Boat?

In simple terms, a flying boat is a seaplane designed with a hull as the fuselage to give it the ability to take off and land on water. It differs from float planes in that float planes gain buoyancy from pontoons, or floats, under the fuselage and wings.

During the Golden Age of Flight, things were different than they are today. Innovation and experimentation were much more common. Designers often came up with imaginative solutions to the technical limitations of the era. The flying boat design was one approach that proved popular. Nevertheless, the design fell out of favor by the 1960s.

It might surprise younger readers, but the flying boat used to be a significant part of aviation. Many countries employed them in their militaries while commercial airlines like Pan American Airways — later known as Pan Am — employed them for passenger routes. In fact, if you’ve ever seen Raiders of the Lost Ark then you’ve seen Indiana Jones taking transcontinental flights on them.

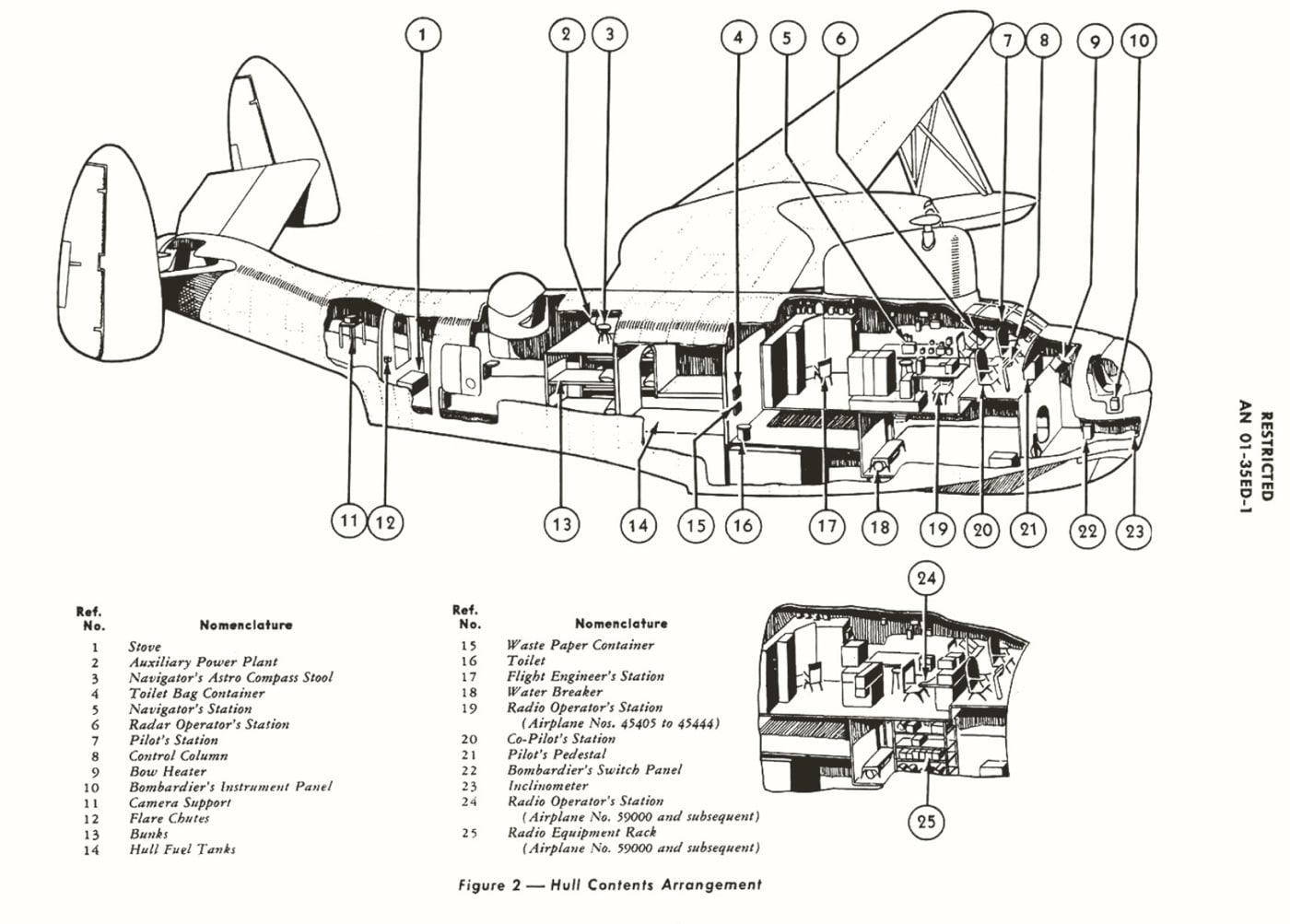

Because hull integrity is a real thing, the vast majority of Mariners did not have traditional landing gear. That meant that PBM aircraft could only take off and land in the water. Aircraft could be refueled and supplied on the water.

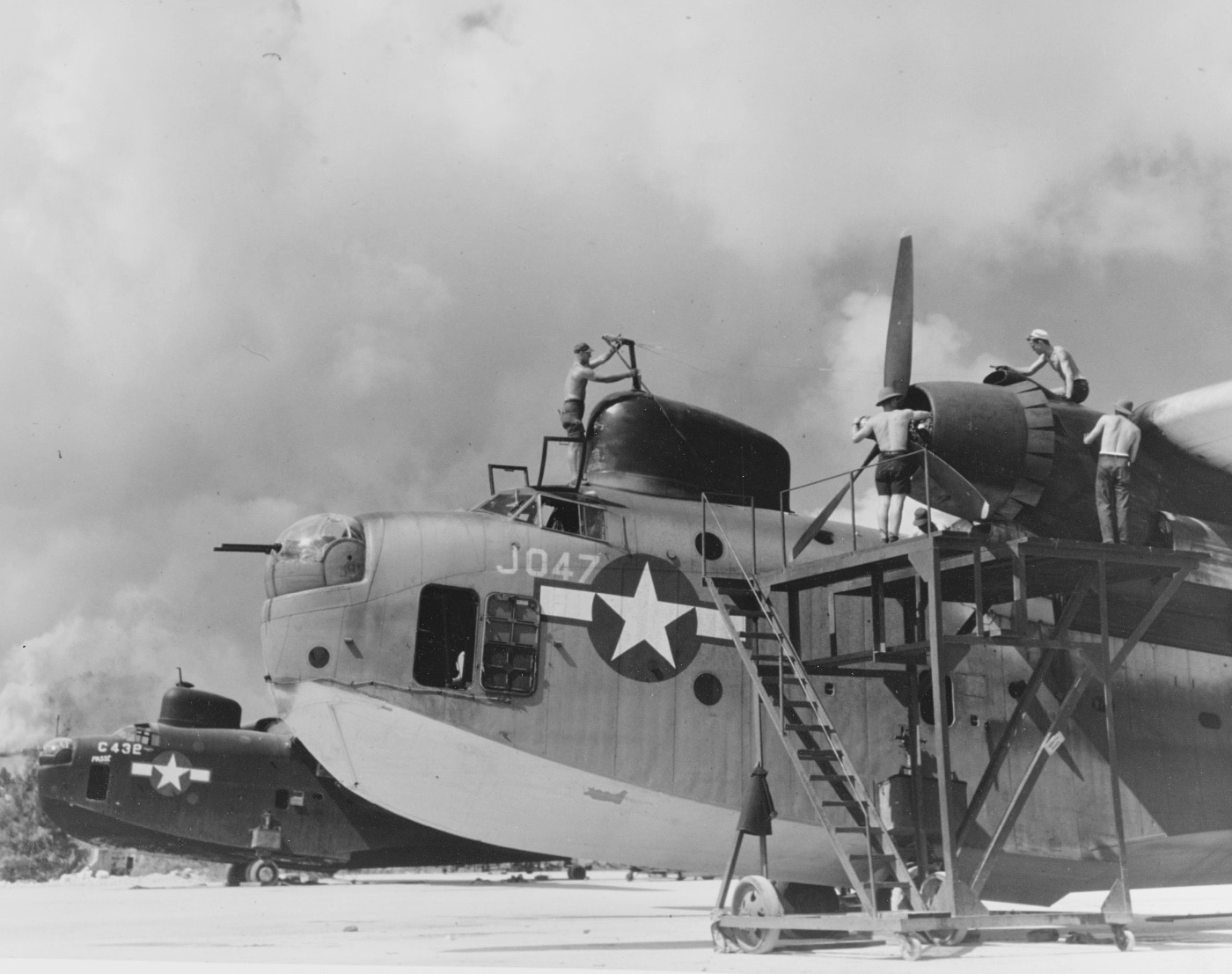

For servicing, they could be lifted by a seaplane tender out of the ocean. Likewise, they could be fitted with temporary beaching gear so the aircraft could be pulled onto land.

Believe it or not, flying boats are still used today. In fact, there are several flying boats still in production including the Dornier Seastar and the new AVIC AG600.

“Real” Bomber

While the U.S. Army Air Force is often associated with the “real” bombers of World War II, the Martin PBM was a legitimate bomber. The first PBMs to enter service could carry 4,000 pounds of bombs. Later PBM models with more powerful engines and fewer defensive machine guns maxed out at more than 12,000 pounds of ordnance.

PBM Mariners could deliver a variety of ordnance including 500-lb., 1000-lb. and 1,600-lb. bombs, depth charges, mines and torpedoes. Bombs were loaded in enclosed compartments in both wings below the engine nacelles. This allowed the plane to remain streamlined while ensuring the integrity of the watertight hull.

Additionally, torpedoes could be attached to the exterior of the PBM wings.

As with many capable military planes, there were a variety of models made. Three main models were made — the PBM-1, PBM-3 and PBM-5 — with several subvariants built for specific missions including anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and transport.

Bristling with Guns — Armament

PBM patrol bombers were most often equipped with Browning M2 .50-caliber machine guns. They were intended for two purposes — defense against enemy fighters and attacking surfaced submarines.

While depth charges were more frequently used against German U-boats and other Axis submarines, PBMs have numerous documented uses of the M2 machine guns against enemy subs. Over in the Pacific Theater, PBMs downed multiple Japanese fighters that mistook the PBM for an easy target.

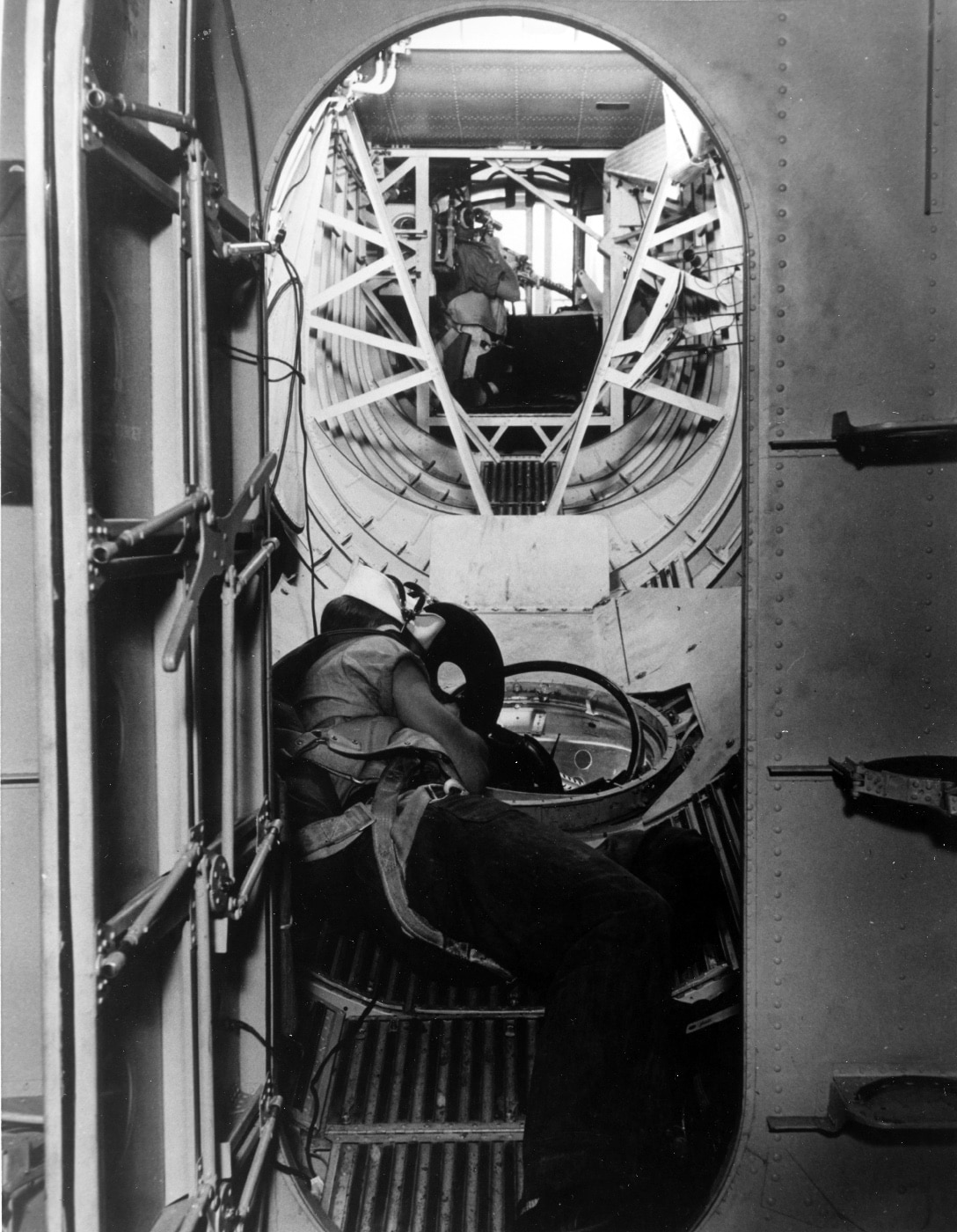

In many configurations, the PBM had eight M2 machine guns. A pair were in a nose turret, a pair were in the dorsal turret and another pair were in the tail turret. Amidships, single M2 machine guns were found on both sides of the fuselage — not unlike the waist gunner positions of a B-17.

A single .30-caliber machine gun could also be found in the bottom of the fuselage between the main cabin and the tail gunner position. While not as powerful as the .50s, it could still be a nasty surprise for any fighter jock who tried to attack the plane’s belly.

Some variants, notably early models and ASW-specific models, of Martin PBMs had fewer machine guns to improve patrol range. Transport models typically had no machine guns. The planes were quite versatile and readily accepted multiple configurations.

Anti-Submarine Patrols

Martin PBM aircraft were used in a wide range of activities. It is probably best known for its sub hunting capabilities in World War II. PBM patrol bombers could be equipped with depth charges and Mark 13 torpedoes. It is believed, however, that all PBM attacks on submarines were made with depth charges and none with torpedoes. Torpedoes were used against surface ships.

Many PBM aircraft used for anti-submarine warfare were equipped with radar and AN/ASQ-1 Magnetic Airborne Detection Equipment — or MAD gear as it was more commonly known. PBM aircraft with MAD gear could be recognized by the addition of two streamlined housings that were attached to the top of the wingtips.

Neutrality Patrol in the Atlantic

Starting in 1939, war raged in Europe. German U-boats prowled the Atlantic Ocean seeking to stop men and supplies from reaching Europe. At the same time, Allied naval forces blockaded Germany. Called the Battle of the Atlantic, it was the longest continuous campaign of the Second World War.

Ostensibly, the United States was neutral at the outset of hostilities. Within days of panzers rolling into Poland, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the United States a neutral power. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Navy began the Neutrality Patrol using both ships and planes to defend American interests.

When Martin PBMs began entering service in September 1940, they were almost immediately deployed to support the Neutrality Patrol. In July of 1941, British ASV radar units were added to a pair of PBM patrol bombers. Not only did this enhance the capabilities of the aircraft, but it also marked the first instance of a U.S. Navy plane being equipped with radar.

Battle of the Caribbean

As part of the Battle of the Atlantic, both Italian and German submarines deployed to the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico to attack Allied shipping. PBM crews saw extensive service in this region. In the summer of 1943 alone, Martin PBMs sank five German U-boats in the Caribbean and surrounding waters.

However, Germany had upgraded its anti-aircraft capabilities on U-boats, and they were a much more dangerous prey. A quad-20mm autocannon was installed on some U-boats. Called the Flakvierling 38, these AA guns were lethal against low-flying aircraft. Three PBMs were shot down and several more were significantly damaged.

During the war, PBM crews were credited with sinking 10 German U-boats, which amounted to slightly more than a third of all U-boats sunk by U.S. patrol aircraft.

Pacific Theater Deployments

While the PBM Mariners were used to hunt Japanese submarines, they were frequently used for attacking Japanese convoys, bombing land targets and rescuing flight crews.

Most frequently, PBMs operated solo. That means the crews had to be self-sufficient and work well together. One crewman stated that the men who served on his PBM respected rank and protocol on the ground but were a tight-knit family in the air. Sailors cross-trained to other positions on the plane to increase resiliency in combat.

Attacks on ships and subs while on patrol were often conducted alone. Likewise, defense against Japanese fighters did not have the benefit of a massed herd of planes, a strategy effectively employed by the U.S. Army Air Force over Europe.

For attacks on land targets and harbors, several PBMs would act as a team. This typically meant that two, three or four Mariners would act in concert. Mass bombing raids were uncommon.

For bombing missions, the U.S. Navy developed a modified version of the Norden bombsight. Ordnancemen trained with the Norden prior to deployment to the fleet in a PBM. The reality seemed to be that the bombsight was rarely used as the PBMs were frequently used for very low-level bombing operations that made the Norden superfluous.

Attacks were frequently made at less than 500 feet — often half or less than that. By comparison, the smaller B-17 Flying Fortress typically made bombing runs above 20,000 feet.

Dumbo Missions in the Pacific

The United States Navy used the PBM frequently for Dumbo missions. Dumbo missions, named after the Walt Disney cartoon character, were search and rescue missions to pick up downed aviators who had to ditch their planes.

Frequently, PBMs would coordinate these Dumbo missions with air raids and other military operations. However, the Dumbo monicker would eventually become synonymous with any search and rescue mission.

The PBM was an excellent Dumbo aircraft due to its long legs and ability to land in the ocean. If the seas were suitable, a PBM could set down and pull flight crews right out of the water. If the water was too rough, the PBM could drop rafts and other supplies and loiter overhead to coordinate a rescue with Allied ships.

Dumbo missions could be long and dull, but they were incredibly successful overall. In a 1945 Time magazine article, the author cited a government report that documented more than 2,000 pilots and air crewmen who were rescued between June 1944 and June 1945.

Korean War

In addition to ferrying men and material early in the conflict, the U.S. Navy used the PBMs to conduct long-range patrols of the waters around the Korean Peninsula. Further, PBM crews were tasked with eliminating enemy mines in harbors and other areas.

On at least one occasion, a PBM carried an Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) to Inchon for reconnaissance ahead of Operation Chromite.

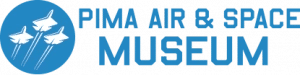

Bomber with a Kitchen

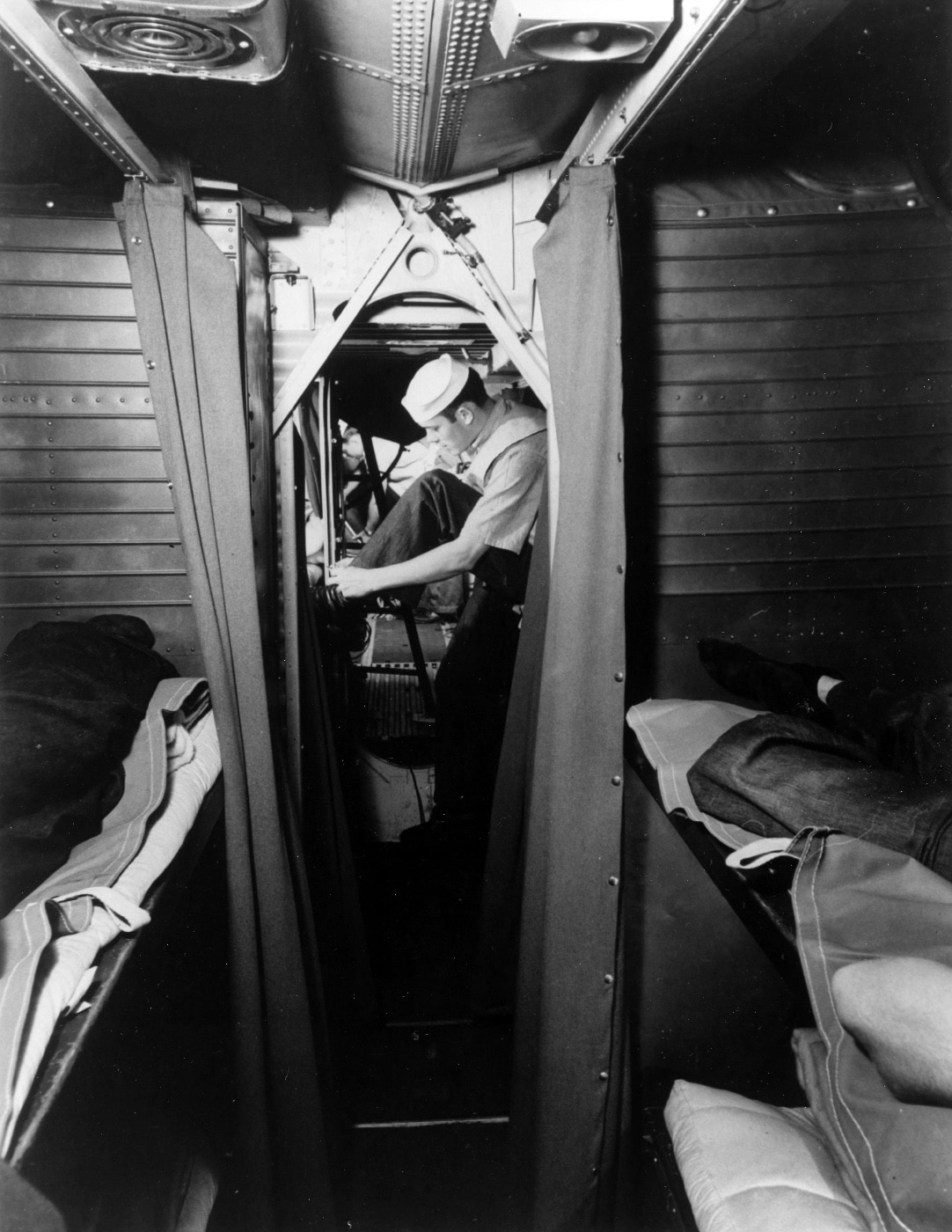

Martin PBM aircraft were large enough to have a bathroom, bunkroom and a galley aboard. The bunkroom had four bunks to allow passengers and crew to get some downtime on long trips.

The galley wasn’t a gourmet kitchen, but it was a functioning area that allowed crewmen to cook up a decent meal. Likewise, the head was fully functional, albeit modified for a plane.

For crews on a long patrol or ferry, these amenities were priceless. Likewise, they made the plane suitable for transport of flag officers and other dignitaries.

Jet-Powered Flying Boat

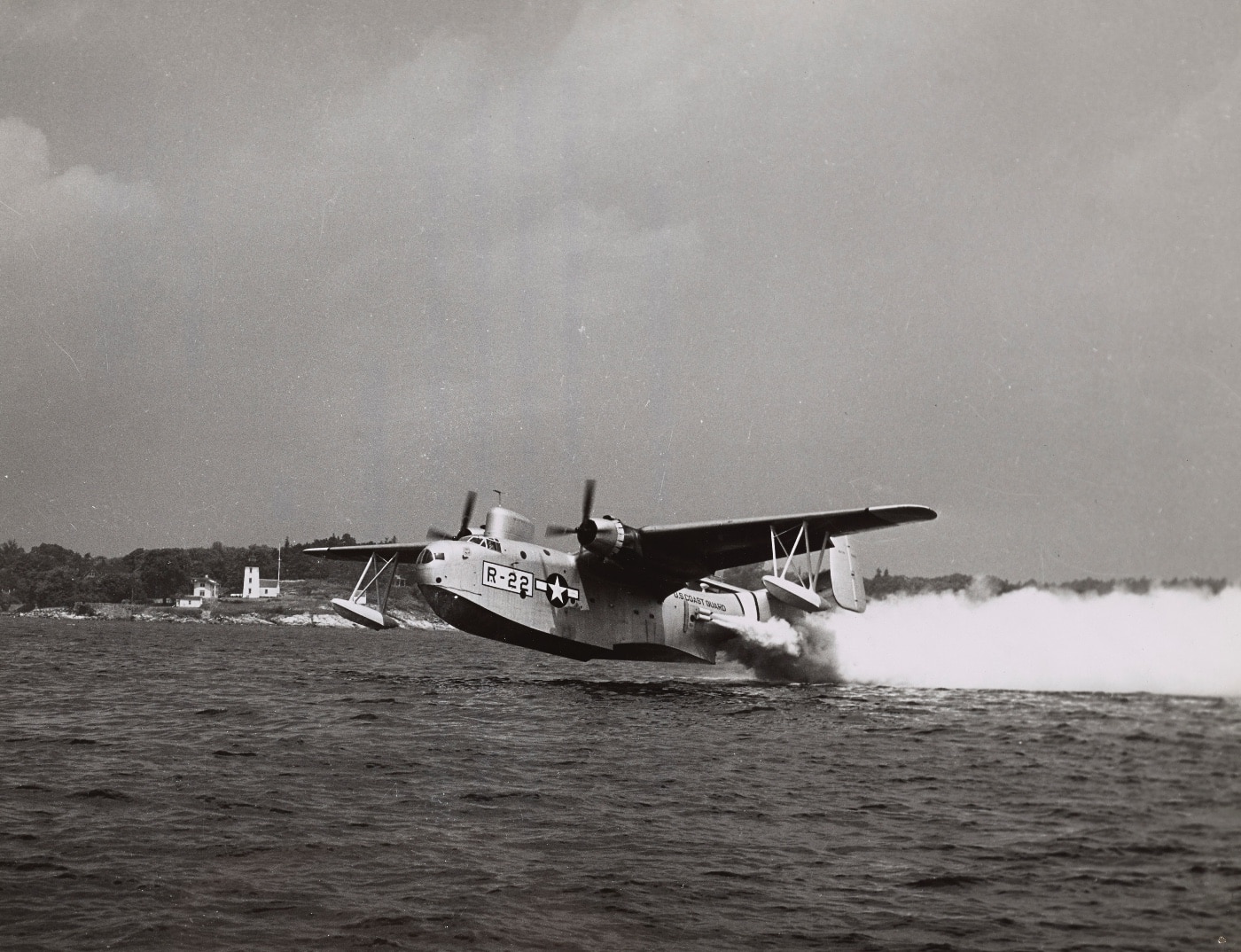

While the twin-engine PBM had excellent flight characteristics, it also had the issues inherent with water take-offs. Simply speaking, getting big planes into the air from the water takes time and space. Choppy water makes takeoff even more difficult.

Martin experimented with different ideas, including a catapult barge that would launch the planes in a manner similar to an aircraft carrier. In the end, however, a simpler solution was utilized: jets.

Jet-assisted take-off (JATO) canisters were fitted to some PBM planes. These canisters were used to shorten the take-off distance substantially — especially on rough waters.

PBM Use by Allied Countries

In addition to the United States Navy and Coast Guard, Martin PBM variants were used by the Argentine Navy, Dutch Navy, Panamanian Defense Forces, Royal Australian Air Force and Uruguayan Navy.

The United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force received 54 PBM patrol bombers. After testing, however, the Brits believed the planes were too taxing on their pilots to fly. They wound up returning all of the PBMs without flying any of them in combat.

Final Thoughts on the PBM

Like many men of his era, my father volunteered for the Navy during World War II. After getting his mother’s permission due to his young age, he enlisted in 1943 not knowing that it was the first step in a nearly 21-year career.

Growing up, he talked about some of his experiences — mostly interesting stories from all the times between the wars. He almost never talked about World War II or Korea. It wasn’t until the last years of his life that he shared any of those stories with me or my brother. Frequently, his time with PBM Mariner and PBY Catalina flying boats would be part of his recollections — the good ones and the bad.

Martin PBM Mariners saw combat in World War II and the Korean War. They’ve engaged in combat against the communists of both China and the Soviet Union outside of declared hostilities. Yet, try to find a single PBM in a movie.

The more I learn about the planes, the men, the squadrons and their missions, the more I realize their story needs to be told.

There is one surviving PBM flying boat in the world. Held by the National Air and Space Museum, the surviving PBM-5A (U.S. Navy serial number 1220714) is on display at the Pima Aerospace Museum. Interestingly, it is one of only 40 PBM aircraft that was built or retrofitted with retractable landing gear. Located in Tucson, Arizona, the museum is open every day of the week. If you have the chance, I recommend visiting and checking out its massive collection.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here