In 1933, engineer Donald Roebling wanted to find a way to save people stranded in disaster. After the 1926 Miami Hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane that resulted in thousands of deaths in South Florida, the need for a rescue vehicle was real. Roebling’s father suggested Donald build a machine to “bridge the gap where a boat was grounded and a car flooded out.” Unexpectedly, Donald Roebling’s philanthropic invention of the Alligator would eventually carry U.S. Marines to victory in the World War II Pacific campaign.

It was fitting that Donald Roebling’s father used the term “bridge the gap” in his suggestion. Donald’s great-grandfather, John Augustus Roebling, designed New York’s Brooklyn Bridge, and his grandfather, Col. Washington Augustus Roebling, completed the plans and built it. Engineering was in the Roebling DNA. Donald would construct his part of the family legacy in Clearwater, Florida.

Designing the AMTRAC

The Alligator was conceived as an amphibious tractor, or an AMTRAC, which could bring aid to victims on land or sea. Thought of by Roebling as a “Mercy Machine,” his tractor would plow through the most inhospitable swamp areas and then operate as a boat on the water with its tracks providing the propulsion. In a fortuitous twist of fate, the United States Marine Corps was at that time considering a vastly different application for an AMTRAC.

Donald Roebling began constructing prototypes for his Alligator and had a functional platform completed in 1935. Experimentation on the Alligator took place in Roebling’s personal workshop at his grand Spottis Woode estate on the Intracoastal Waterway in Clearwater. Components were also built in a secondary shop in the neighboring town of Belleair.

The initial challenge was the material used for the waterproof hull. Roebling settled on duralumin, an alloy of aluminum. It was lighter than steel, yet strong enough for the boxy structure. Duralumin was used for aviation in the 1920s and 1930s, notably for frames of airships such as the German Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg, and the American USS Los Angeles, Akron, and Macon. Roebling had to explore methods for working with this new material for the Alligator.

Roebling also struggled with his cleated tracks as they proved unreliable in hard use, but he was doggedly determined to build a vehicle that relied on the single-drive system to work on both land and water. His persistence was rewarded as he developed rugged, efficient tracks and obtained U.S. patent #2138207 for his system.

By 1937, the Alligator was in its fourth iteration. Model IV was approximately 20 feet long, 8,700 pounds, and could reach 18 mph on land and nearly 9 mph in the water. All prototype testing was done near Clearwater at the waterfront bluffs in Belleair, Honeymoon Island, and Dunedin.

After concluding military operations in Haiti and Nicaragua in the mid-1930s, the U.S. Marine Corps was interested in developing a doctrine for fighting on amphibious terrain, especially for the transport of men and material from ship to shore. The Marines had tested a Christie amphibious light tank in 1924 but found it unsuitable for rough seas.

In the Spotlight

With Roebling rambling his rescue vehicles about in marshes, mangroves, and the beaches of Pinellas County, these activities drew the attention of the staff of Life Magazine. On October 4, 1937, Life ran a story about Roebling and his Alligator under the Science and Industry heading on page 94 of the issue. Included were photos of the AMTRAC being put through its paces.

The Life article attracted the attention of U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Edward Kalbfus, who in turn, shared it with U.S. Marine Corps Major General Louis McCarty Little, who commanded the Fleet Marine Force. As the story goes, Gen. Little sent a copy of the article to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General Thomas Holcomb. With a veritable ammo crate of brass enthused by the Alligator and its potential to solve the puzzle of amphibious landing, it was assured that Roebling would be consulted.

In February 1938, the Marine Corps sent a letter of interest to Roebling. He promptly responded, “The Alligator may be inspected, and we will be glad to demonstrate it to you at any time.” Mere weeks later, Marine personnel were scrutinizing the Alligator. The next two years would be marked by further examination and jumping through the many hoops of bureaucratic procurement procedures.

The Department of the Navy contracted with Roebling on February 22, 1940, to build 200 Alligators. The price would be 3.3 million dollars. With no way to manufacture the vehicles on such a scale at his estate, Roebling subcontracted with the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) in Dunedin, Florida, just north of Clearwater, to build combat-ready steel Alligators. Later versions would be produced at plants in Lakeland, Florida; Riverside, California; and San Jose, California.

Landing Vehicle Tracked in Combat

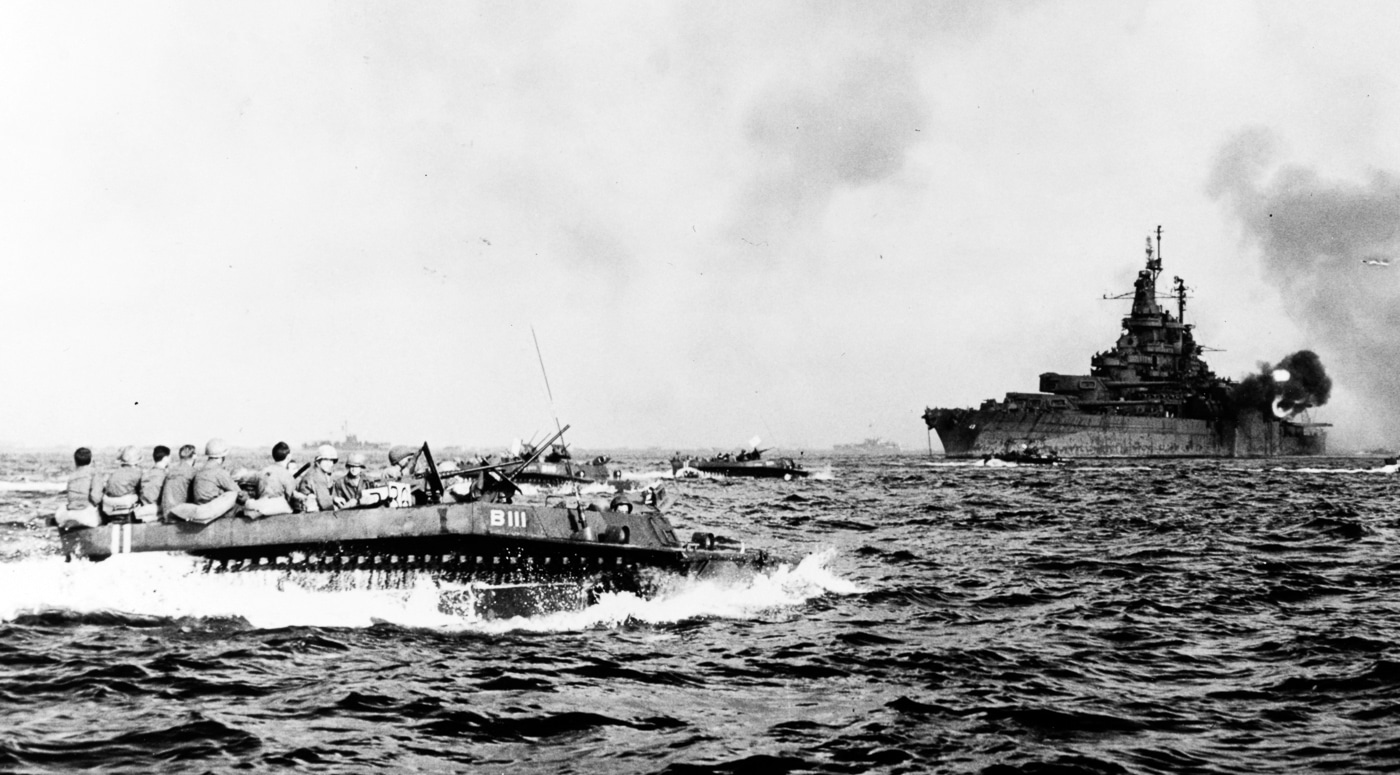

The first Alligators that were delivered to the Marines became known as the LVT-1, or Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Model 1. Roebling’s original Mercy Machine had proof of concept. The LVT-1 joined combat at the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Many variations of the LVT would follow and serve with distinction during the war. Even the current Marine Corps AAV, Assault Amphibious Vehicle, is a descendant of Roebling’s original requirements.

“There is not the slightest shadow of a doubt that the overwhelming victories of our forces at Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Palau, and Iwo Jima would not have been possible without the AMTRACs,” said Vice Admiral E.L. Cochrane, WWII chief of the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships. More than 18,000 LVTs would be built between 1941 and 1945.

While the Dunedin FMC factory that built Alligators is now a parking structure, there is still pride in FMC’s contribution. The Veterans of Foreign Wars SPC Zachary L. Shannon Memorial Post 2550 in Dunedin has a refurbished LVT-4 on display. I took a quick drive over and was honored to have some vets take my photograph with Roebling’s innovation.

In Recognition

Roebling received a U.S. Navy Certificate of Achievement in recognition of the “exceptional accomplishment” of the Alligator. In 1948, he was awarded a Medal of Merit from President Harry Truman, “for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service to the United States.”

For a man with the vision of saving thousands of people from storms, Donald Roebling possibly saved millions with an invention that would move military might in both the Pacific and European Theaters and help the Allies win WWII. Roebling quietly resumed his amusements of mechanical tinkering, stamp collecting, and HAM radio in the post-war years. Roebling never accepted personal compensation for the Alligator and gifted the patent to his tracked system to the U.S. government. He passed away in 1950.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here