“Masters of the Air” stands as a landmark in telling the American World War II story in popular media. The expansive and expensive nine-part miniseries — which aired in 2024 on Apple TV+ — was designed as the third part of a trilogy that included the massively successful “Band of Brothers,” followed by “The Pacific.” They were long and difficult productions, and I was honored to serve as Senior Military Advisor on all three.

We did mountains of research on the 8th Air Force in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) generally, and specifically the activities of the 100th Heavy Bombardment Group (The Bloody Hundredth) which was selected as representative of the air war in Europe for the series.

Maybe it was my background as a former enlisted man or just my instincts to cheer for the underdog, but I was concerned from the start of our training period and throughout the production in the UK that there be an accurate depiction of the air gunners who flew on all Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress missions.

Usually in a dramatic, character-driven production, the emphasis tends to be on the officers up front — the pilots, navigators and bombardiers. However, I wanted to make damn sure the unsung and under-appreciated air gunners got the attention they deserved.

During training and prior to committing anything to cameras, we used a crawl, walk, run approach. World War II flight crews were trained as soldiers before they went on to mission-specific bomber crew duties, so we began with the basic soldier stuff including proper wear of the uniform, PT, close-order drill, and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) organization to include customs and courtesies. Then it was time to get specific with a special emphasis on the performers who would portray air gunners.

Training B-17 Gunners — Where To Begin

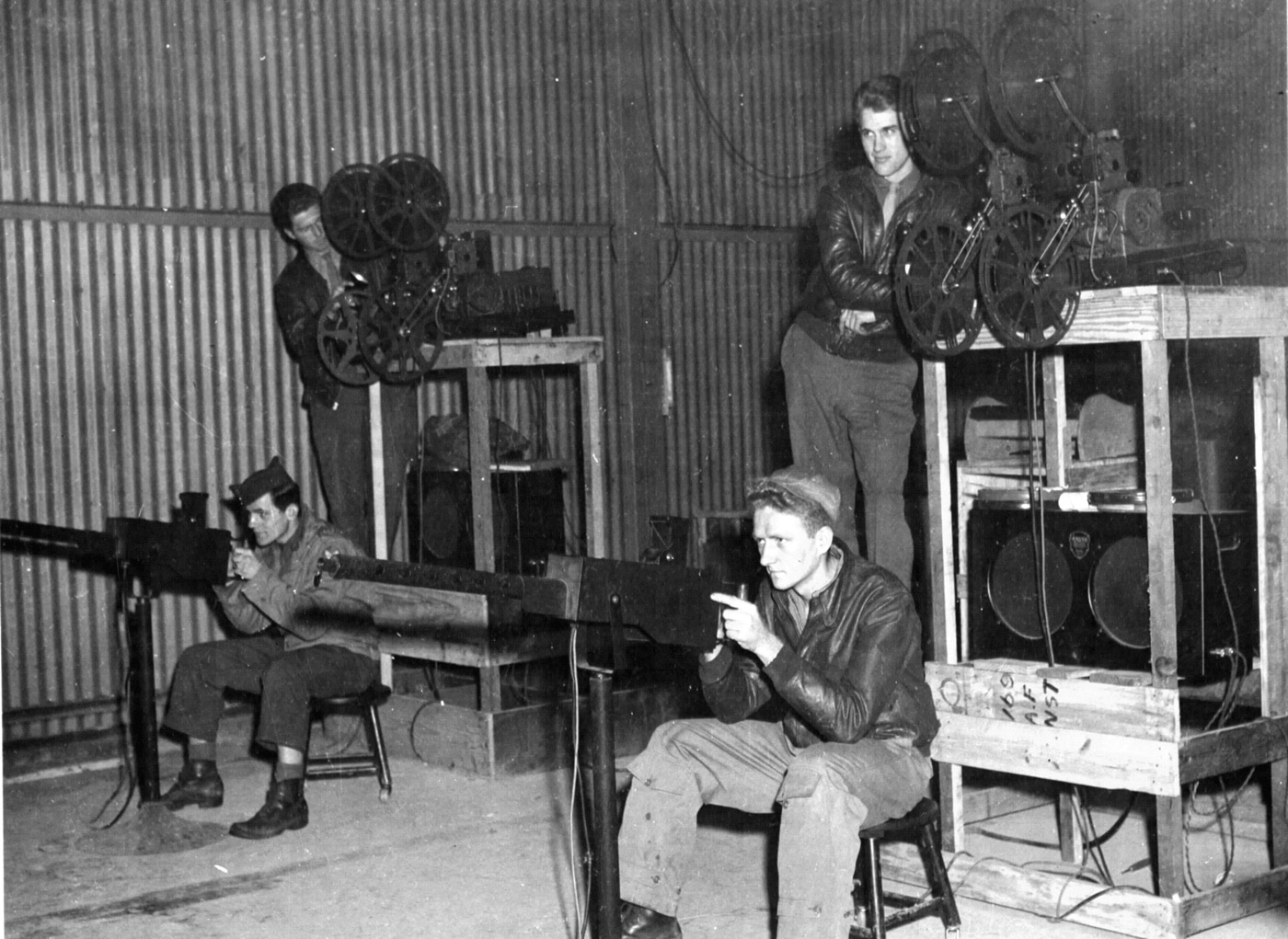

We started training them on the real .50-cal. Browning M2HB, with four blank-adapted guns on a firing line at our training site. They got a taste of taming that beast by loading and firing in short bursts from a flex-mount. While they wrestled with the bolt handle, feed chutes and stiff recoil springs, we reminded them that they would be simulating all that at high altitude wearing oxygen masks and heated suits in sub-zero temperatures.

Touching the gun’s metal parts without thick gloves would lead instantly to frost-bitten and useless hands. Ammo was fed to each gun through a series of metallic chutes and trying to link extra belts into a gun while airborne at altitude was a trick that every B-17 air gunner had to master given the AN/M2’s ammo-eating rate of fire.

The “Ma Deuce” can be a bear to handle under any conditions, but we wanted to ensure they understood — and accurately portrayed — the problems with taming a .50-cal. machine gun in a vibrating aircraft at extreme altitudes.

The Real Experience

To hammer the point home, toward the end of the training period, we dressed all our actor aircrew out in everything the men they were portraying would have worn on a real-world mission in World War II. This included a basic uniform shirt and trousers, a set of blue long johns and the leather electrically heated trousers and fur-lined jackets.

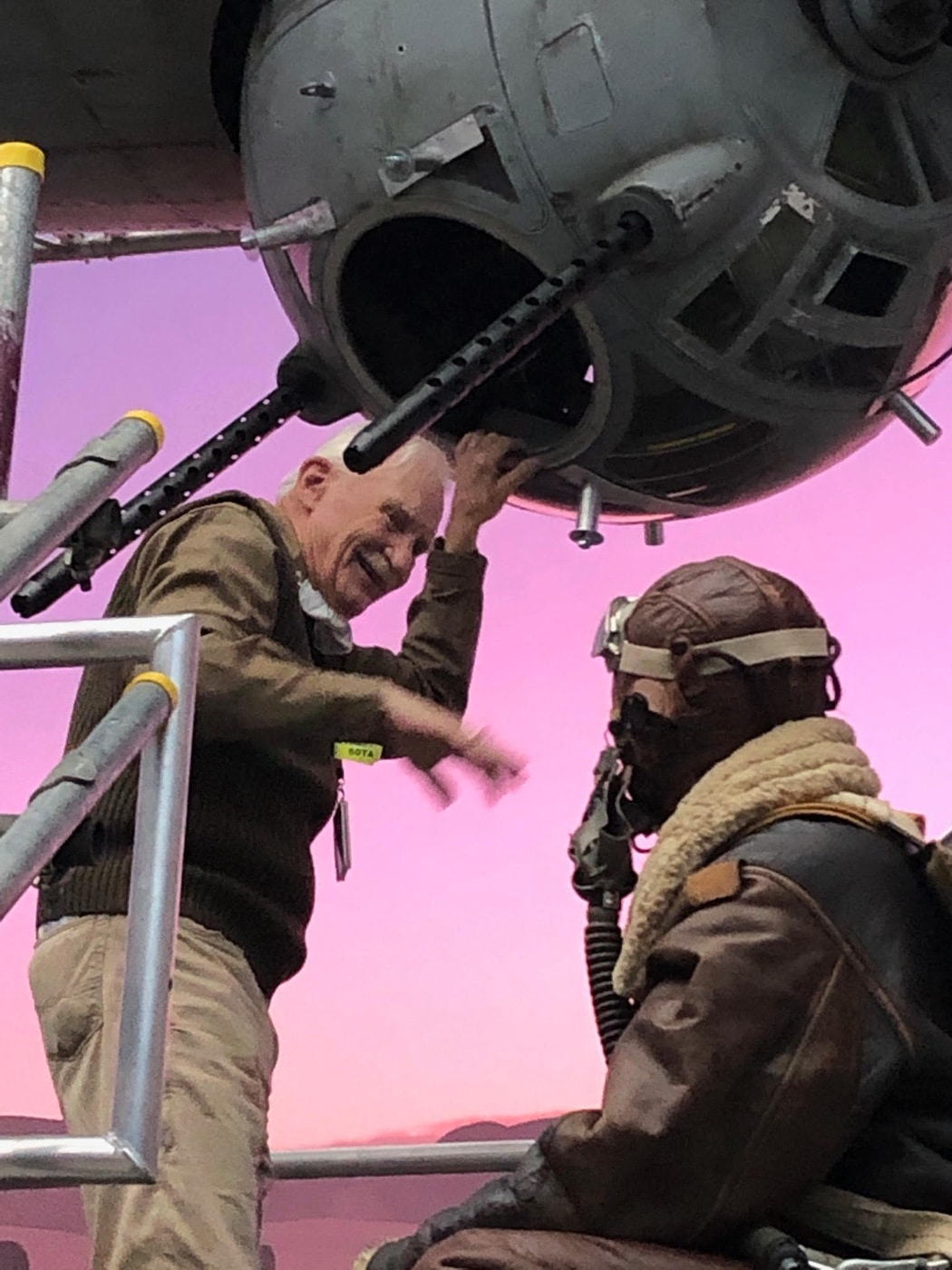

Added to their misery were extra sweaters, scarves and fur-lined boots, plus helmets, goggles and period correct earphones and throat mics. They waddled to the gimbal-mounted B-17 mock-ups and got some serious experience in moving around a bouncing, bucking airplane while dressed like the Pillsbury Doughboy.

We were rotating gunners through various aircraft positions one day when I noticed we had a man missing at muster. He was a big guy who had been cast to portray a tail gunner, which meant he spent hours crammed into a narrow tunnel, straddling a little bicycle-type seat at the end of the B-17.

When we finally found him beet-red, sweating and nearly passed out in the tail position, we had to shoehorn him out into the open air. Between the mouthfuls of water I forced him to chug, he squinted up at me and said, “You mean those guys stayed in there like that for eight or 10 hours?”

[Learn more in this article on How Effective Were B-17 Gunners?]

They did. And so did he when we were shooting long, continuous scenes of an aircraft in flight. Training like this brings understanding, and understanding pays dividends on camera.

Working Together as B-17 Crewmen

A B-17 Flying Fortress crew of 10 men could be conceptually divided like a modern football team into offensive and defensive players. On offense were the two pilots, bombardier, navigator and radio operator (RO).

It’s not an exact analogy, as in some B-17 models the RO was equipped with an AN/M2 .50-cal. machine gun, and the bombardier and navigator up in the nose bubble also had a pair of .50’s in flexible cheek mounts. But, manning those weapons was secondary to their primary missions.

On defense — a crucial element in surviving relentless German Luftwaffe attacks on bomber formations — were the air gunners: Tail gunner with a pair of .50s, ball-turret gunner and top turret gunner (who also served as flight engineer) with paired .50s in turret mounts, and the two back-to-back waist gunners firing single guns in flex-mounts.

Identifying and calling out enemy fighters was another challenge. We spent hours studying and identifying German aircraft types and working the high-low clock references that would quickly alert the crew to inbound threats. That was particularly difficult for tail gunners who had to remember they were flying backwards, so their clock was reversed.

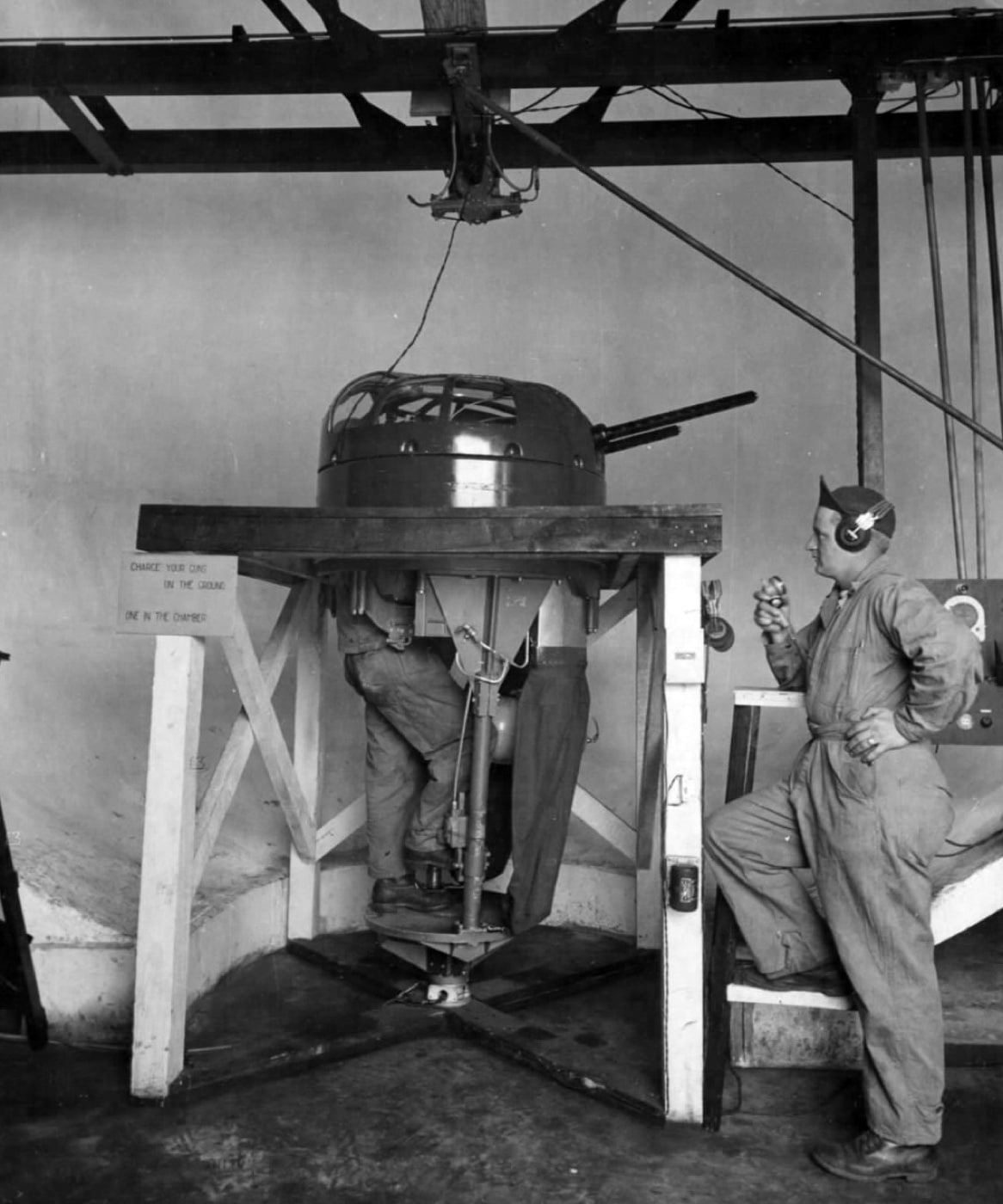

We had good mock-ups provided by brilliant technical designers and engineers, so training while stuffed into a cramped turret was effective for top turret and ball turret gunners. They spent hours whirling and spinning in these torture devices, and that gave them a solid feel for what it was like in a turret trying to fend off fighter attacks.

When we got to the mock-up ball turret for training, I had four young actors who were not at all anxious to cram themselves into that underslung goldfish bowl in which gunners laid on their backs with their feet up in the air at about shoulder level. Asked how it went after their first experience, one of my guys just shrugged and massaged his sore back. “OK, I guess. Good practice if you’re having a baby or getting a prostate exam.”

Making It Count

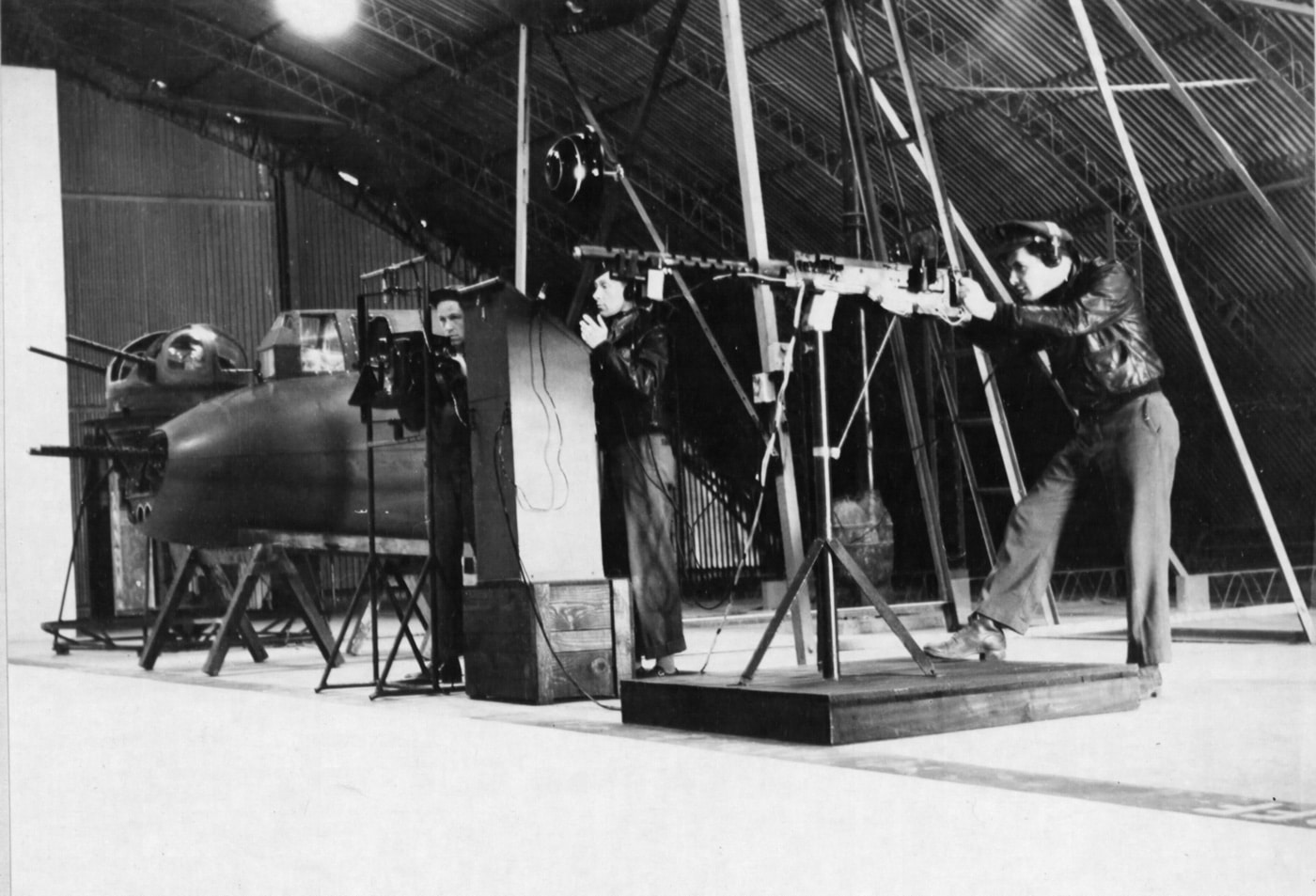

Machine gun marksmanship and aiming was another training challenge, especially for the right- and left-oriented waist gunners. They were only slightly offset from direct back-to-back positions in the middle of the aircraft and were firing from open ports that made wind a factor in controlling their weapons.

In addition, you can’t use the old duck-hunter “lead” in firing from an aircraft that is moving in one direction while your target is moving in any one of several others. Also, with other B-17s flying next to you in tight formation, you can’t just pray and spray lead everywhere. With engagement ranges of airborne targets beginning at about 600 yards and these powerful .50-cal. guns, that’s a recipe for fratricide.

The machine guns we used in actual filming were gutted, pneumatically operated versions of the World War II-era AN/M2. While they were balky at first, they eventually ran like Swiss watches. We wound up with mounds of .50-cal. casings to sweep out of fuselage sections at the end of every shooting day.

Importantly, the waist gunners got a feel for the tripping hazards big piles of shell casings presented as they swiveled along with computer-generated targets projected on all-surround screens in front of them.

Fog of War

Some stats regarding enemy aircraft destroyed by heavy bomber air gunners may come as a surprise. From November 1943 to April 1944, over the course of a thousand recorded engagements in which enemy aircraft were confirmed as destroyed, 5.1% fell to ball turret gunners, 15.6% were nailed by waist gunners (each side), 17.2% went down under fire from top turret gunners, and 30.5% fell to tail gunners.

World War II air gunners bitched loudly about such stats, but it was hard in those days — in a chaotic sky filled with heavy bombers and blazing machine guns — to keep accurate track. An enemy aircraft destroyed (versus damaged) was often claimed by multiple gunners in multiple aircraft. Additionally, a crash or bail-out by an enemy fighter pilot had to be verified by a second observer. Confirmation was often arguable and hard to come by in over-heated post-mission briefings.

[Don’t miss Tom Laemlein’s article, America’s Unknown Gunner Aces of World War II.]

Conclusion

While “Masters of the Air” as a series was mostly snubbed during Emmy considerations, the reward for those of us involved was watching the young actors we’d trained mount up in those B-17 mock-ups every day looking as if they were born to it.

They moved smoothly and confidently and knew all the hazards and shortcuts by first-hand experience, just as the real air gunners and other crewmen did during the real war.

That’s the sort of thing that counts for us filmmakers of the genre, and it adds up to a long-overdue salute for the men who took up these dangerous and deadly missions.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here

![Best Tactical Lever-Action Rifles [Field Tested] Best Tactical Lever-Action Rifles [Field Tested]](https://i2.wp.com/gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/tactical-lever-action-rifle-feature.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)